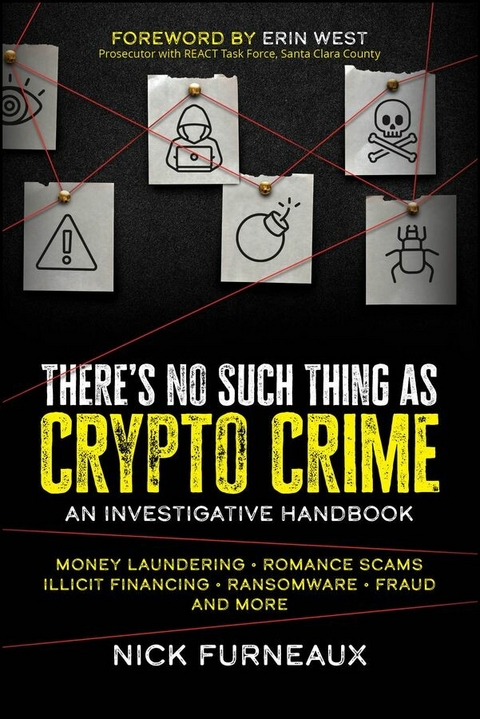

There's No Such Thing as Crypto Crime (eBook)

528 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-394-16483-7 (ISBN)

Hands-on guidance for professionals investigating crimes that include cryptocurrency

In There's No Such Thing as Crypto Crime: An Investigators Guide, accomplished cybersecurity and forensics consultant Nick Furneaux delivers an expert discussion of the key methods used by cryptocurrency investigators, including investigations on Bitcoin and Ethereum type blockchains. The book explores the criminal opportunities available to malicious actors in the crypto universe, as well as the investigative principles common to this realm.

The author explains in detail a variety of essential topics, including how cryptocurrency is used in crime, exploiting wallets, and investigative methodologies for the primary chains, as well as digging into important areas such as tracing through contracts, coin-swaps, layer 2 chains and bridges. He also provides engaging and informative presentations of:

- Strategies used by investigators around the world to seize the fruits of crypto-related crime

- How non-fungible tokens, new alt-currency tokens, and decentralized finance factor into cryptocurrency crime

- The application of common investigative principles-like discovery-to the world of cryptocurrency

An essential and effective playbook for combating crypto-related financial crime, There's No Such Thing as Crypto Crime will earn a place in the libraries of financial investigators, fraud and forensics professionals, and cybercrime specialists.

NICK FURNEAUX is a cybersecurity and forensics consultant specializing in the prevention and investigation of cybercrime. Nick is author of the 2018 book Investigating Cryptocurrencies and has trained thousands of investigators in the skills needed to track cryptocurrency used in crimes. He works within the training academy at TRM Labs, and is an advisor to the Board of Asset Reality.

1

A History of Cryptocurrencies and Crime

Driving the Harbor Freeway north out of Los Angeles toward Pasadena, you pass by the densely populated residential areas of South Park and Vermont Harbor before likely noticing the huge sporting complex that includes the LA Memorial Coliseum and the Bank of California Stadium on your left. As you pass under the Santa Monica Freeway and swing to the northeast, the vast LA Convention Center comes into view and behind it the famous home of the LA Lakers basketball team. This arena had for decades been known as the Staples Center, named after its sponsor, the vast multinational office supplies organization. However, a person driving past around Christmas 2021 would have noticed the familiar Staples signs were gone and had been replaced by a name written in blue and white. Crypto.com Arena.

For many, this would have been the first time they had seen or heard of the name of one of the largest cryptocurrency exchanges in the world. Although just five years old when they took over sponsorship of the Lakers home, the Singapore-based company had tens of millions of customers around the world and represented just one of the many cryptocurrency exchanges dealing billions of dollars of virtual currencies every day.

A few months later, during the 2022 Super Bowl, arguably one of the most expensive sporting events in the world for a company to advertise their services, five cryptocurrency exchanges ran TV advertisements or social media campaigns to coincide with it. Crypto.com has gone on to become a sponsor of the FIFA World Cup, and Formula 1 cars in 2022 displayed the logos of Binance, Bybit, Tezos, FTX, and other cryptocurrency brands. Cryptocurrencies were now squarely in the public consciousness.

At a governmental level, having long ignored or simply criticized digital currencies, countries started to wake up to the fact that these new currencies were here to stay. Although much of their early use was arguably by a mix of hobbyists, conspiracists waiting for the new world order, and criminals, now middle-class people living in the suburbs were beginning to take an interest and buy into this new investment opportunity. Newspapers and social media were running stories of the vast profits to be made, and many with some spare cash wanted in, arguably driven by a new acronym, FOMO, or fear of missing out. Anecdotal accounts of people remortgaging property to buy Bitcoin appeared in the more sensationalist press, and futures contracts and shorting options began to be made available, often by brand-new, unregulated companies.

Legislation was badly needed, and suddenly governments became more aware of the issue and started to respond. First, bodies such as the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, and the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK began to react to the complex issues of companies trading cryptocurrencies. Second, the tax authorities started to consider the difficulties of tracking and charging tax on the highly volatile and anonymous nature of crypto assets. Lastly, central government caught up, and by 2022, President Biden had signed an executive order (Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets—March 9, 2022), and legislation for the “regulation of stablecoins and cryptoassets” appeared in the British Queen’s Speech (https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/queens-speech-2022-economic-affairs-and-business).

Other countries responded in a rather more binary way by either banning cryptocurrencies, as did China and Indonesia, or conversely welcoming them, including El Salvador, who made Bitcoin legal tender in 2021, followed by the Central African Republic.

It is notable that it is generally countries that are experiencing difficulties with their primary fiat currency that are reacting in these more contrasting ways to cryptocurrencies.

NOTE Fiat money is a government-issued currency that is not backed by a physical commodity, such as gold or silver, but rather by the government that issued it.

As mentioned earlier, El Salvador reacted to financial pressures by welcoming Bitcoin. Turkey, in the midst of crippling inflation (mid-2022) of the Turkish lira, banned the use of Bitcoin for paying for goods and services. People were turning to cryptocurrencies as a “stable” alternative to the lira, which is extraordinary when you consider how volatile the Bitcoin price can be. Governments will continue to struggle with this new challenge to their traditional centralized, government-controlled currencies for some time to come.

As I stated previously, arguably, cryptocurrencies are part of the public’s consciousness in many countries around the globe, but why is this of interest to criminal investigators? To answer this question, we need to briefly look at the history of cryptocurrencies, which will help us understand their appeal to criminality.

Where Did It All Start?

English words have an odd way of changing their meaning. In the 13th century the word “silly” was someone pious or religious; however, by the late 1800s the word carried the meaning we have today of someone or something being foolish. “Crypto” has become one of those words that used to mean one thing but is now generally recognized as referring to something else. If just two or three years ago, you had asked any technologist what the word “crypto” referred to, they likely would have all responded that it was a shortened form of the word “cryptography.” Cryptography has to do with the securing of data either in transit or at rest through, historically, the use of codes and ciphers, and in recent times something we will explain in more detail later known as public/private key cryptography. But as I’m penning this chapter, if you ask either a technologist or just a person on the street what “crypto” is, they will probably say Bitcoin, Ethereum, or cryptocurrencies, or something similar. Why has this change to the generally accepted meaning of the word happened? Certainly, in the English language we do love to shorten words (my actual name is Nicholas but the only person who ever called me that was my mum when I was misbehaving!) and crypto is much easier to say, and definitely easier to type, than cryptocurrency.

The reality is that the two meanings are closely linked. The crypto part of the word “cryptocurrency” comes from the fact that all cryptocurrencies have their transactions and transaction ledgers confirmed and protected by cryptography. In the case of Bitcoin and its derivatives, it uses a quite simple form of cryptography and it’s very secure but fundamentally straightforward. It’s a mistake to read online about all the hack attacks and losses of digital currencies like Bitcoin and think that there is something wrong with the code or the cryptography underpinning it. Bitcoin has never suffered from a successful attack against its source code or crypto. We will discuss in more detail how attacks against users and custodians of cryptocurrencies can fall prey to criminals in Chapter 2, “Understanding the Criminal Opportunities: Money Laundering,” and Chapter 3, “Understanding the Criminal Opportunities: Theft.”

Although you do not need to become a cryptographic scientist to understand how these systems work, it is still useful for an investigator to have a good idea of how cryptocurrencies are protected in order to better grasp some of the attacks against them. We will discuss this in more detail in several of the early chapters.

From a criminal perspective, cryptocurrencies offer opportunities that are difficult to achieve through the traditional banking network. We shouldn’t believe that crypto is anonymous—every transaction is recorded on the blockchain ledger for anyone to study. The issue for the investigator comes from the fact that it is difficult to connect a cryptocurrency address to a user. This pseudo-anonymity provides opportunities to hide movements of assets, pay for or receive payments for illicit goods, or target others’ crypto assets, in an environment that is challenging for the investigator to analyze. As this book will outline, difficult does not mean impossible.

Although this chapter is called “A History of Cryptocurrencies and Crime,” I wrote a deeper background of crypto assets in my book Investigating Cryptocurrencies (Wiley, 2018) and I won’t go into as much detail here. However, I think it’s worth the investigator being aware of the accepted stepping-stones of crypto up to the present day and how they relate to the changing shape of crimes that utilize cryptocurrencies.

Most articles and books written on the history of cryptocurrencies point back to a cryptographer named David Chaum, who created an early form of electronic money called DigiCash in 1989. Others believe that the 1998 Bit Gold concept by Nick Szabo was closer to our concept of a cryptocurrency, where a predecessor of the concept of “mining” by solving algorithmic problems was implemented. Interestingly, Nick also wrote a white paper in 1994 in which he described in significant detail the concept of a digital, or smart, contract, which was an agreement between parties based purely on a coded contract with no third parties involved.

But it’s the white paper published in October 2008 by the enigmatic Satoshi...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Mathematik / Informatik ► Informatik |

| Schlagworte | blockchain crime • blockchain investigations • Cryptocurrency investigations • cybercrime • cybercrime investigations • cyber forensics • defi crime • defi investigations • Financial Crime • financial crime investigation • fraud forensics • fraud investigations |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-16483-1 / 1394164831 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-16483-7 / 9781394164837 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 28,0 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich