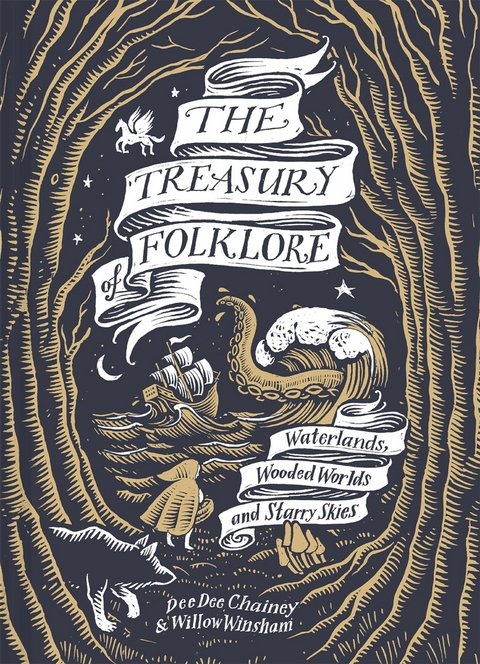

The Treasury of Folklore (eBook)

320 Seiten

Batsford (Verlag)

978-1-84994-977-4 (ISBN)

Dee Dee Chainey is the author of A Treasury of British Folklore: Maypoles, Mandrakes and Mistletoe from National Trust Books. She is co-founder of #FolkloreThursday, a popular website and Twitter account that brings fascinating tales and traditions from all corners of the globe to its followers every Thursday. She currently lives in Liverpool.

Dee Dee Chainey is an archaeologist by training, and author of A Treasury of British Folklore: Maypoles, Mandrakes and Mistletoe from National Trust Books. She is co-founder of #FolkloreThursday, a popular website and Twitter account that brings fascinating tales and traditions from all corners of the globe to its followers every Thursday. Willow Winsham is a historian of witchcraft, specialising in English witchcraft cases. She is author of Accused: British Witches Throughout History and England's Witchcraft Trials. She is co-founder of #FolkloreThursday. Joe McLaren graduated from the University of Brighton in 2003, and now lives and works in Rochester, Kent. He previously taught Foundation Illustration at Central Saint Martins. A superbly talented illustrator, Joe's clients include Penguin Random House, Faber, Orion, Folio, John Murray, Oxford, The Times, The Guardian and The Financial Times.

WOODED WORLDS

WOODLANDS AND FORESTS

Wooded Worlds

Trees are the lifeblood of the earth. Their roots run deep in the soil; they are the veins and arteries of our world, sustaining and nourishing the life of the ground around them. Their very existence replenishes the air we breathe, creating oxygen that sustains most life on our little planet. We are only now beginning to understand the intricate network of trees that cover the land, and how they are able to communicate with each other. Yet the ancients somehow knew this, without the science we have today. They saw how the trees’ branches reached up to touch the heavens and gave a home to the birds of the air. How they dug deep into the soil below us, connecting the skies with the land we walk upon; often stretching out as far as the eye could see, fading into horizons, deep and unknown. Since humanity first walked this earth, the trees have provided sustenance, and we have relied on them to provide our food: from the berries and mushrooms that grow in them, to the animals our ancestors hunted from within their midst. They provide fuel for warmth, and timber for our shelters, as well as for the boats that first carried both people and their wares to distant shores.

Strangely, while trees were once a way for us to communicate with both spirits and gods, now, in the modern day, they are used to communicate our words to others and share our ideas across the globe. The book you are now reading was once part of a tree. And still, we forget them. We cut them down. We burn them, and mould them, and shape them again and again. Yet as we do, their stories linger. We carry the essence of trees with us always. Wherever we live in the world, most of us have woodlands – or even a single tree – that we call our own; trees that we have loved since childhood. They might be horse chestnuts that bear the conkers of our childhood games, conjuring images of soaking the leathery brown balls in vinegar to outrank our rivals, rapping the knuckles of children across Britain. Sometimes they are the argan trees of Morocco with goats clamouring in their branches – something that may seem strange to all but those who know the secrets of the traditions that surround them. For some, they are the great firs of the northern forests, with wild boar snuffling in their snow-covered undergrowth. For others, they are the olive groves of southern Italy, with their gnarled, twisting trunks and roots that venture far into the red earth below them. Wherever we are in the world, our relationship with our trees is symbiotic, irreplicable and timeless.

THE WORLD TREE

For thousands of years people have conjured images of the outermost reaches of the universe they lived within. For many cultures, the cosmos took the shape of a tree, with its branches reaching up to kiss the heavens, and its roots twisting down into the soil of existence. This is what rooted them to their reality and shaped how they saw the world around them. This world tree was at the very core of everything they believed, an indication of how trees have been at the heart of human life since the beginnings of time. We are all creatures of the forests, yet the world trees that span the mythologies of Europe, Mesoamerica and the Near East show how many of us, once, were also people of the trees.

The world tree looks different across the globe, but many similarities exist. Usually, the trees’ branches stretch up, extending into the clouds and beyond, often with a bird at the top. The roots delve deep into the earth, or lie in water, and here there is usually an underworld beast lurking in the depths, symbolizing chaos and creation. In the middle exists the world of humankind. The number of realms or planes the tree encompasses often varies, yet one thing is constant: the tree is timeless and connects all of us to each other and the creatures and spirits of the world. It is a thing of gods, spirits and humankind; it is the place where the spiritual, intangible and physical meet. The world tree is part of the concept of the axis mundi – the axis or central pivot that the world revolves around. In some mythologies, a mountain or pillar plays a similar role to this tree. In Baltic mythology, the saules koks – tree of the sun – is an apple, linden or oak that is entirely silver or gold. Many have searched for it in legends, but no one has ever seen it. In the Batak religion, the banyan tree is seen as bringing the layers of the universe together. Hindu texts also talk of a cosmic tree, a topsy-turvy growing banyan, with the roots in heaven, and branches reaching down to bless the earth.

Yggdrasil

For some, the most famous world tree is Yggdrasil of Norse mythology, said to be an evergreen ash in the poem ‘Völusp’ from the Poetic Edda. Within it lie the nine worlds of the Norse cosmos; some appear vertically along its trunk, while others are arranged horizontally. The realm of the gods lies at the top, the worlds of humankind and giants at the middle, and the underworld at the bottom. The tree is known by the kennings ‘Odin’s horse’ and ‘Odin’s gallows’, as he sacrificed himself by hanging upon it. Its top is so high that it reaches above the clouds and is snow-capped, while winds tear around its branches.

Three roots delve deep into watery places beneath the tree, and different sources say that they are in different locations. One lies over Mímir’s well of wisdom, where the god Odin sacrificed his eye for a drink of the waters. It crosses into the land of the rime giants, which was once where the yawning primordial void of Ginnungagap could be found.

Another root is over the spring Hvergelmir, meaning ‘the Cauldron-Roaring’. This is in Niflheim, a place of mist, cold and ice. It is here that Níðhöggr the monstrous serpent gnaws at the tree’s roots from the dark mountains of the underworld, and sucking the blood of the slain. Hel lives under this root in her underworld realm of the same name, a place of darkness and the dead, some believe to be underground. Hel is sometimes seen as the goddess of death in Norse mythology, a giantess who rules over the portion of the dead who were not taken off to other realms on their passing. It is said half the warriors who fall in battle go to Valhalla, the ‘Hall of the Slain’, ruled over by Odin. The other half go to Fólkvangr, the field of the goddess Freyja; women who have faced a noble death can also reside here in the afterlife. The 13th century Icelandic scholar Snorri tells us at one point that those who die of illness or old age are taken by Hel, yet many suggest he often exaggerated original sources of Norse mythology, while others say he invented his own lore. We do know that Hel is the daughter of Loki and Angrboðr the giantess, cast out by the gods with her siblings, Fenrir the wolf, and the Midgard Serpent, Jörmungandr.

The poem ‘Grimnismol’ tells us that beneath the last root is the land of men, while ‘Gylfaginning’ tells us one is over the well of Urðr in the heavens among the gods, belonging to the three norns who weave the fate of humanity: Urðr, Verðandi and Skuld – representing the past, the present and the future. It is here that the Æsir gods come each day over the rainbow bridge Bifröst to hold court and conduct their business. At the top of the tree is Hlithskjolf, meaning ‘Gate-shelf’. This is Odin’s tower, where he sits with his ravens, Huginn (meaning ‘thought’) and Muninn (‘memory’ or ‘mind’), and watches over all of the nine worlds from the heavens. From here, he sees all – from everything humankind does, to the acts of the gods.

Many animals live among the branches of Yggdrasil. An eagle resides at the top of the tree, and a chattering squirrel, Ratatoskr, runs up and down passing messages between it and Níðhöggr the serpent. The stag Eikþyrnir feeds from the branches of the tree from the top of the hall of Valhalla, the afterlife home of warriors who died in battle. The goat Heiðrún also grazes on its leaves. While both the stag and goat feed from the tree named Læraðr, many identify this as Yggdrasil itself. When the tree shivers and groans it is said that Ragnarok, the end time, is near.

The Sky-High Tree

The Hungarian world tree, égig éro fa, is less well known, but just as magical. It’s said that it grows from the mountain of the world, connecting the upper, middle and lower realms, and both the sun and moon are held within its branches. Snakes, worms and toads live in the roots, and at the top sits a bird, often the mythical turul, the falcon-like bird of prey often seen as a national symbol of Hungary. The tree itself is thought to grow from an animal: a deer or horse.

Many believe the tree has shamanic overtones, showing how people can travel through different realms, of which there are often seven or nine. The ability to climb the tree is restricted to the chosen folk heroes – namely the táltosok, shaman-like figures in Hungarian tradition. A táltos is usually marked at birth to follow the path by being born with teeth or a caul (a portion of tissue or amniotic membrane attached to their head) or having an extra finger. Other signs include late weaning, speaking little, and being withdrawn and aloof, yet very strong. In some regions, an individual would have to pass a test, sometimes...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | Woodcut illustrations |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Historische Romane |

| Literatur ► Märchen / Sagen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | ancient tales • Druids • Fae • Fairies • Folklore • Folk Tales • Goddesses • Gods • Legends • Magic • Mermaids • Mythical creatures • Mythology • Myths • Occult • Occultism • sea monsters • Sirens • Spirits • Tarot • Witches • WitchLit • wizards |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84994-977-8 / 1849949778 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84994-977-4 / 9781849949774 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 20,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich