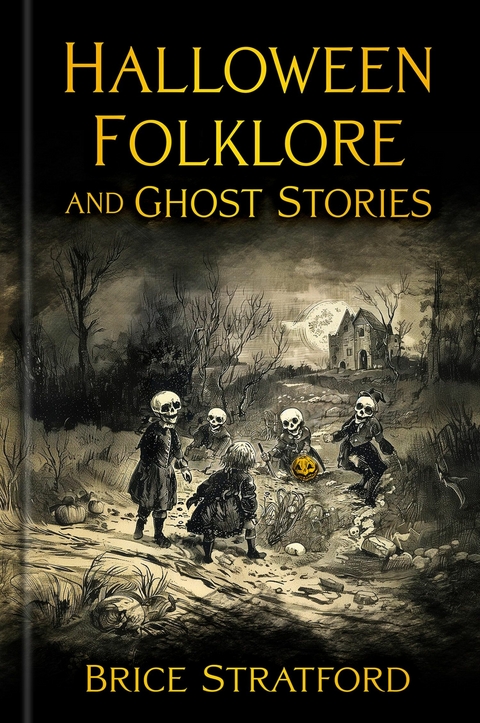

Halloween Folklore and Ghost Stories (eBook)

192 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-775-9 (ISBN)

BRICE STRATFORD is an actor, storyteller, theatre director and local historian. He was born and raised in the New Forest. He currently stands on the Lyndhurst Parish Council, and is especially active in local heritage projects. His theatre company Owle Schreame has won numerous awards and his work has been featured in local, national, industry and international media. A regular fixture at folk and fright events across the country, writes regularly on culture, history, architecture and the arts for the Critic, the Spectator, the British Theatre Guide and Apollo.

A storyteller, historian, folklorist and actor-director, Brice Stratford runs the Owle Schreame theatre company, specialising in obscure historical productions and research as practice. Past work has focused on the British ritual year, and the folk drama and storytelling traditions associated with the seasons. A regular fixture at folk and fright events across the country, he has published two other books, New Forest Myths and Folklore and Anglo-Saxon Myths: The Struggle for the Seven Kingdoms, and writes regularly on culture, history, architecture and the arts for the Critic, the Spectator, the British Theatre Guide and Apollo.

6

THE RICHMOND GHOSTS

Let’s discuss a distinction between two types of story in this book. Some are tales of terrible acts at All Hallows Eve – deeds so striking they burned themselves into the season when first they were carried out and so became entwined with it, producing ghosts which haunt the Hallowtide as memorial to what has come before, be they victim, perpetrator or both. Others, like the Devil of Woodstock, are different; these are hauntings without a clear, worldly origin or instigator. These are ghosts and beings who were born of Hallowmas itself, and begin life as an explicit encounter, with any story or explanation coming second – they were not entwined with the season, but grew from it directly. These are the sort that most often get dismissed as hoaxes, in part because the lack of any origin story makes them essentially inexplicable (odd as it may seem, a clear narrative is usually enough to satisfy people, even if they remain cynical of theactual events within it).

So it is with the Richmond Ghost. Or one of them, at least.

Much as we take the credulity of olden times folk for granted, in the majority of historical accounts the first presumption is scepticism. People know what bedsheets and shadows are, and in the past were far more used to the flickerings produced by firelight than you or I, and far less likely to be gulled by them. Just as many enjoy stories of ghosts, and just as many more believe them, when an encounter is thrust upon the public, just as many people are desperate to believe that there’s a good, solid earthbound explanation at the bottom of it.

It is likely for this reason that, lacking a narrative of its own, the baseless ‘explanation’ for the Devil of Woodstock has been grasped at so uncritically and by so many. Most people do not want their perceptions challenged or their world views rocked. When an excuse to dismiss comes along, which allows them to maintain unaltered the view that’s served them thus far, more often than not, they will take it.

The vast majority believe or disbelieve based on bias and prejudice. Either they automatically believe accounts of hauntings because they long ago committed to believing in ghosts, or alternatively, their logic rigidly goes that ‘there is no such thing as ghosts, therefore it is not a ghost, therefore it is a hoax’ – both conclusions will be reached regardless of context or evidence.

As it is almost impossible to prove a negative, and as most sightings are long past the potential of any real investigation, such hauntings can be termed ‘Schrodinger’s ghosts’ – as the reality of them is purely experiential and subjective. Until the point that they are proved unambiguously to be either genuine or fake, they exist simultaneously as both real and unreal, both prankster and spirit. True to those who believe, untrue to those who disbelieve, with neither position rooted in anything beyond the self.

Speaking of ghost sightings in these terms allows us to put to one side the messy matter of truth or fiction and to take an account on its own merits. It also allows those with a predisposition in either direction to suspend their belief or disbelief and focus on the story as we have it. We can acknowledge compelling evidence and dismiss shoddy theories, regardless of the directions such things may point in, as we are no longer discussing the nature of objective reality or life after death – merely the quirk of a Schrodinger’s ghost.

A particularly good example of a Schrodinger’s ghost can be found in the Halloween season of 1801, in the town of Richmond in Surrey, today a suburb of Greater London. The astute among you will notice parallels with the infamous and far better-known Spring-Heeled Jack, who would first appear to terrorise London thirty-six years later, at Christmas of 1837. But Richmond’s ghost is a Halloween ghost, and blazed the trail that would later be followed by Jack and many others.

Unlike at Woodstock, initially this was a case of an itinerant haunting – a traveller-botherer, or spectral visitant, who came to houses door to door as trick-or-treaters do, rather than being restricted to a single dwelling place. This is an extremely obscure case, barely spoken or written of today (indeed, it may not have been written about at all), though it caused a severe stir two and a bit centuries ago. It unfurled, as I have said, towards the end of October 1801.

The first mention I can find is in the Morning Post of 28th October that year, where we are excitedly informed that ‘the inhabitants of Richmond, in Surrey, have been for some time in a state of alarm at the appearance of a ghost in that neighbourhood, which shews itself to several persons under a variety of forms’.

The ‘variety of forms’ is an interesting element, as the article goes on to describe two very different ghosts that, for some reason, have been assumed to be the same creature in different guises – why they are not considered to be two separate beings is never specified (ghosts, after all, are often like buses – you wait ages for one, then two come at once). The first ‘is all black, with a long tail, bearing the human form’, while the second ‘appears in white, with black face and black hands’ – the article implies multiple encounters with both forms, but does not specify which in the brief selection that follows:

To one lady it appeared a few nights since at her bed-chamber window, on a moonlit night; the church bell was at the moment striking the hour of twelve. The lady was found by the servants (whom she had called to her assistance by ringing the bell) in a swoon, and was with difficulty restored to her senses. A young girl, walking near the [Richmond] Theatre at a late hour, was tapped on the shoulder by the ghost; she was so much frightened as to be confined to her bed ever since. Two ladies and a gentleman were walking by the water side on Friday evening last, when one of the ladies suddenly exclaimed, ‘There it is now!’ This exclamation had such an effect on the gentleman, that the ladies, notwithstanding their fright, were obliged to support the gentleman to the town, or he would have fainted.

The paper goes on to tell us that ‘the town is all in confusion, and two guineas reward has actually been offered to any one who can discover the ghost’. That’s approximately £200 today, so certainly worth exchanging gossip for; and so, it seems, was the case, as the article concludes by telling us that ‘a lady, an inhabitant of the place, has left it in consequence of one of her sons being accused of knowing the ghost’.

Things apparently continue, and the Richmond ghost quickly becomes the talk of the chattering classes. The wry and gossipy society paper, The Porcupine of 30th October comments that ‘the Richmond Ghost [occupies] so much of the conversation of our females and fashionable petits maitres, that they can scarcely find time to say their prayers’. The article goes on to refer to the ‘two guineas reward for the discovery of the Ghost with a Black Tail’.

The London Courier confirms that, as of 7th November, ‘The Richmond Ghost continues to excite much alarm in that neighbourhood’, but by Martlemas Eve, circumstances had, according to the Oracle and Daily Advertiser of 10th November, ‘completely exorcised the Richmond Ghost, who now lies (as the Village Gossips say) buried in the Red Sea “full fathom five”’.

The full story of the ghost’s undoing (and consequent loss of Schrodingeral status) is given at the end of the month in the London Courier on 28th November, where it’s referred to as ‘The Kew and Richmond Ghost’, and we are told of a subtly different modus operandi:

The neighbourhood of Kew has of late been extremely alarmed by the report of a ghost having been seen in different places about the fields, whose nocturnal visits to the pale glimpses of the moon excited such terror, particularly among the females, that hardly one could be prevailed on to stir out at night, the spectre, all in deadly white, being sure to meet them at some convenient gate or turning: those who did not believe in such supernatural appearances very properly resolved to detect the imposition, and for the better doing it, offered [£20] reward [given in the original text as ‘20l.’, this is probably an exaggeration rather than a genuinely increased reward from the 2 guineas already mentioned] to any person that would apprehend the ghost, either alive or dead; when lo! a few evenings since, a labouring man, defying the Devil himself, seized the spectre, who, as a proof of his being corporeal, offered the man [£40] to let him go; but this was refused, and on an investigation taking place, it appears that the imposter is the son of a gentleman in that vicinity, who had clothed himself in a white sheet, to carry on the farce; a custom that would certainly be more ‘honoured in the breach than the observance.

That seems to be the mystery solved, though an unnamed ‘son of a gentleman’ is an extremely common (and completely un-evidenced) explanation for such things, often given when no other materialises. This is quite aside from the fact that a young man in a white sheet (presumably his face and hands would have to be painted black, though this is not specified) hardly explains the sightings of the other form – a black, humanoid figure with a long tail and nothing white at...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Historische Romane |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Horror | |

| Literatur ► Märchen / Sagen | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | Allhallowstide • christian mythology • Customs • dark folklore • Fairy tales • folk stories • Folk Tales • Ghost Stories • Halloween • halloween folklore • hallowmas • horror folklore • Jack O'Lantern • legengs • Myths • pagan beliefs • pagan gods • paganisn • Pixies • scary folklore • Short Stories • Traditions |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-775-3 / 1803997753 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-775-9 / 9781803997759 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 18,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich