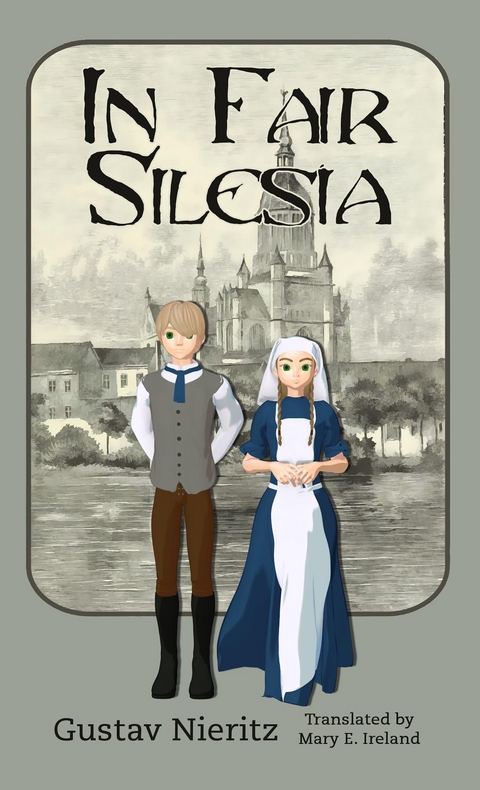

In Fair Silesia (eBook)

156 Seiten

Writers of the Apocalypse (Verlag)

978-1-944322-73-1 (ISBN)

Joseph and Helena are so poor their mother can not afford to feed them. They must go to live with their uncle in Reichenstein. They hope to get a job in the factory, like other children do in their time, and build a better life for themselves.

Little do they know what they must face now that they've left the mountains.

When In Fair Silesia was first published in 1894, it was commended for its 'distinctive German flavor' and as a 'faithful representation of life as it exists among the people of the author's native land'. Over a century later, this delightful reader stands as a window to life in the Industrial Revolution and the way Christian values permeated the culture enough to be expressed so strongly in the author's words.

Joseph and Helena are so poor their mother can not afford to feed them. They must go to live with their uncle in Reichenstein. They hope to get a job in the factory, like other children do in their time, and build a better life for themselves.Little do they know what they must face now that they've left the mountains.When In Fair Silesia was first published in 1894, it was commended for its "e;distinctive German flavor"e; and as a "e;faithful representation of life as it exists among the people of the author's native land"e;. Over a century later, this delightful reader stands as a window to life in the Industrial Revolution and the way Christian values permeated the culture enough to be expressed so strongly in the author's words.

Leaving Schellerhaus.......................................... 9Uncle Ruckert................................................... 22They Take A Walk............................................ 31Visit To The Proprietor...................................... 43The Revolving Shaft.......................................... 55Schoolmaster Krown......................................... 69Frau Eckhardt's Visit......................................... 85New Machinery................................................. 95The Attack..................................................... 108Many Changes................................................ 124The Oder River............................................... 136Return Home ..................................... 143

Chapter III

They Take A Walk

JOSEPH was awakened the next morning by a clashing, rolling, rumbling sound, which alarmed him so much that he sprang from his bed and ran to Helena’s door to awaken her, thinking that the factory was on fire.

His Uncle Ruckert had left the office, and the children had no one to ask as to the terrible noise. They dressed hastily, and went to the place from whence the most of it seemed to proceed, opened a door, and saw a huge black object in what seemed to them the bottomless pit, and which shook the floor upon which they were standing, and, in truth, the whole factory resounded with the noise of machinery which it was keeping in motion.

That which they had thought to be a great fire was only the factory, set, several hours before, in working order for the day; and, closing the office door, they went out in search of their uncle. They met many men and women with baskets of wool, most of which was already spun, and at length they saw the spinning master.

“Well, sleepyheads!” said he, “I suppose you would have slept until noon if you had not gotten hungry. What brings you out here? Are you hunting your breakfast?”

“We were frightened at the noise; we thought that the factory was on fire,” said Joseph.

“Go back to the office, and I will give you something to eat.”

The children obeyed, and in a few minutes the spinning master, having finished his duties for the time, which had called him from his office, came in, gave them their allowance of bread and cheese, and pointed to the water can.

“Can you read and write?” questioned he of Joseph, when their breakfast was finished.

“Yes; I am twelve years old and a few months over, and have been to school for four years.”

“Good!” responded Ruckert. “Here is a column that I wish you to add up, and here is pen, paper, and ruler. Now do it right, or you will be sorry for it. And the girl, what can you do?" turning to Helena.

“I can sew, and spin flax, and cook.”

“Cook!” echoed her uncle, sneeringly; “I suppose all that amounts to is the making of gruel, and boiling potatoes in their jackets. But I will see what you can do at sewing. Here is a vest that needs mending and several buttons; I expect you to do it well, and to darn these stockings neatly; but first give the canaries their seed and fill their cups with fresh water. I will keep you both for two days, although I do not thank your mother for putting two such millstones about my neck.”

These words dampened the gratitude that the children had felt for the good bread and cheese; they looked at each other and remained silent; and Ruckert, locking the desk as though afraid to trust them so long with its contents, left the room.

"The poor birds, how shamefully they are treated!” said Lenchen, glancing at the neglected cages. “I am glad he told me to attend to them, for it worries me to see the helpless little things trying to take their baths in their drinking cups, in which there is but a few drops of water, anything but fresh. How can they be happy and sing in such a place?”

While talking she was busily engaged in preparing a cage for thorough cleansing. The work for all the birds was done thoroughly, fresh water and seed given, then taking a piece of paper in her hand she went out for the fine, white sand she had seen the evening before near the pump.

She had secured it, when hearing a pleasant voice address her she turned, and saw the girl whom she had noticed in the carriage the day before, the daughter of Herr Laudermann. She had a handsome glass pitcher in her hand, and passing it to Helena, asked her to fill it.

“Oh! It came near being broken,” said Helena, in a startled tone, as she loosed her grasp upon it too soon when passing it filled to the girl, who fortunately caught it, "I would have been very sorry, for it is so beautiful.”

“We have far prettier ones than this, and yesterday we bought a lot of glassware at Warmbrunn, so there was no need for you to turn pale with fright thinking you were letting this one fall. What is your name? Mine is Toska Laudermann, and what made that red mark on your cheek?”

"Helena Eckhardt, and your coachman struck me with his whip.”

“Was it you who got up behind our carriage yesterday?" inquired Toska, reddening. “It was my brother Adolph’s fault, for he told Hans you were there. Was it your brother who was with you, and did he get hurt?"

“Yes, it was my brother, and he has a welt on the back of his neck.”

"Where do you live?"

“In Schellerhaus, up in the mountains.”

“Are you and your brother to work in our factory?”

“No, we are only to visit our Uncle Ruckert; we are to go back in two days.”

"Do you want to go?"

“No, we would rather stay.”

“Who makes you go?”

“Our uncle; he will not keep us, although our mother wrote to him that she could not earn enough to keep us in clothes and food.”

“I never heard of such an uncle as that, if—”

“Toska, why don’t you come with the water,” cried a woman’s voice from the front door of the dwelling.

Toska hurried away, and Helena went into the office with the sand, supplied each cage, then set down to the mending.

“Dear, dear!” said she after inspecting the hose, “it is no use trying to mend these, the heels are so worn. I will knit new ones in, but first will wash them; I wish I had a piece of soap, but will have to wait until uncle comes back.”

“There is a little piece over there by the beer tank, why not use that?” suggested Joseph.

Helena was quick to avail herself of this; the stockings were washed and put in the sun, and she turned her attention to the rest, while Joseph, who had counted over his column several times, tried it once more to see if the result would be the same, and was satisfied that it was correct.

“I would like to know what we are to have for dinner,” remarked Helena, as her needle flew in and out; “I see no kitchen, nor stove, nor fire, nor pans; neither do I see potatoes, nor anything else to eat, and I am getting hungry. What do you think about it, Joseph?”

“I think that I am nearly starved; but it is not the first time, and we made no fuss about it, either.”

At that moment a shrill whistle sounded through the great factory, the signal for the noon rest and dinner, and their uncle entered the office. His first glance was at the canaries, but whether he noticed the improved condition of the cages or not, Helena could not tell. He turned from them to the chest, took from it a cloth, and spread it upon the table, from which he had removed papers and books, and had scarcely finished putting on plate, knife, and fork, when a woman came in with a basket, in which was his dinner, and a pitcher of water. She cast a look of surprise upon the children, which they returned with interest, as she put upon the table a piece of fat pork, a dish of potatoes, and six dumplings. Then she left the office.

Ruckert put a small slice of the meat, a potato, and a dumpling upon a plate for each of the children, to which he added a small piece of bread.

“Now go where you please to eat, but not here,” he said. “I want this hour to myself, and will not be disturbed. And another thing I wish you to remember, and that is, not to go near the schoolhouse of Caspar Krown in the village. If I hear of that, or hear of his name being spoken by you, you will find yourselves sent back to Schellerhaus.”

The children took the plates, and found a shaded place back of the factory, where they sat down to eat.

“It is real good,” commented Joseph. “If mother was with us it would taste much better. I could eat more if I had it; couldn’t you Helena? ”

His sister nodded her head in the affirmative, and they sat for a while in silence.

“I wonder why uncle doesn’t want us to see the schoolmaster,” said she. “He appears to be afraid of him.”

“And isn’t it strange, Helena, that it is owing to a boy that we have never seen but once, and to a man that we have never seen at all, that we are not sent back to Schellerhaus?"

"If we had not met the boy, we would not have heard of Herr Krown,” remarked his sister. “I am glad that we met him.”

“Now that our dinner is finished, we might take a walk and look about us. We have a good half hour, and can see a good deal in that time. Stick the plates and other things in the bushes, and let us go.”

“No, somebody might take them, and uncle would be angry. I will take them back and put them by the office door.”

This was quickly done, and they set out upon their walk. The dwelling of Herr Laudermann was the first place inspected, and they stood at the garden fence, looking at the flowers and at the summerhouse covered with vines; then they walked on, and were in Reichenstein almost before they knew it. The church with its tower, the white marble monuments in the churchyard, and the small, but neat dwellings of the weavers, were all objects of interest.

At length they came to a large house, over the door of which were the words “C. Krown, Schoolmaster,” and the children halted, and looked at each other in joyous surprise.

Without intending to disobey their uncle, they had come to the very place that they had been forbidden to come, and through the clear windows they could see desks and benches, all empty, for it was noon, and the children had gone home to dinner.

They wandered on until they reached a hedge at the back of the garden, where they heard the sound of a man’s voice, cheery and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.12.1894 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Historische Romane |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Neuzeit bis 1918 | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | 1800s • children • children's book • Christian • christian living • Country • Factory • German • Germany • Good Samaritan • historical fiction • History • Industrial • Industrial Revolution • insurrection • linen • Orphans • Rebellion • Revolution • Silesia • uprising • Victorian • worker's rights • YA • Young Adult |

| ISBN-10 | 1-944322-73-6 / 1944322736 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-944322-73-1 / 9781944322731 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich