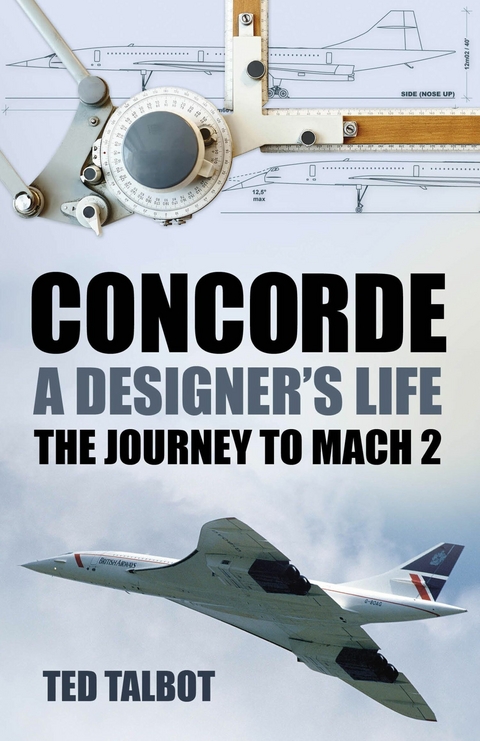

Concorde, A Designer's Life (eBook)

400 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-9632-0 (ISBN)

TED TALBOT studied engineering and aerodynamics before beginning work at Bristol Aeroplane Company as an aerodynamicist, working up to chief design engineer. He worked on major projects from Concorde to Airbus while still finding time to indulge in such hobbies as power flying, gliding and self-building a car and a narrowboat.

PROLOGUE

At the head of the long table that stretched down the briefing room sat the Chief Test Pilot, his Deputy and the other members of the Flight Test crew. They wore the ‘heads are going to roll’ expressions that they had picked up from their French opposite numbers. On the pilots’ right sat the Flight Test Observers with their records of the day’s flight – the ‘ObsLogs’ – waiting to correct the pilots’ impressions of the sequence of events as diplomatically as possible without making it seem as if the pilots were wrong. On their left sat the Chief Inspector, the Ground Crew Chief and their assistants, waiting to find out what had stopped working, had broken or had fallen off. They were wondering if they had overlooked something, or whether they could pass the buck to the design office.

At the foot of the long briefing room table sat the representatives of the design team trying to look nonchalant, but inwardly itching to know how the tests had worked out. Post-flight rumours based on information from the man listening in on the VHF radio were not very promising. Could it be that there was something even more fundamentally wrong than the functioning of the pilots’ seats and the location of their coffee cup holders?

The atmosphere, thick with cigarette smoke from those who had to smoke and of peppermint from those who were trying not to, was forgotten as the Chief Test Pilot delivered his brief: ‘Then there was a bloody great row. Smoke on the flight deck. It sounded like World War Three had started!’

The Deputy Chief Test Pilot later added his sixpennyworth: ‘Just like being in a train smash – and when all four engines surge it’s like being in four train smashes.’

It was quite evident to the representatives of the design team present that the test pilots had been impressed when their first experiences of engine surge on the prototype aircraft at high supersonic speed crept up on them unexpectedly. The aircraft inspectors’ eyebrows were raised in unison and they turned, as was their custom, to look accusingly at the design engineers. Few of the Flight Department had taken note of the warnings given to them about the effects of supersonic surges and were now wishing that they had done so. However, it was not the inspectors’ fault, the designers had designed the thing and something had gone wrong, so it was obviously all due to ‘them’.

Had ‘they’ got it wrong yet again?

‘They’ now realised that achieving Mach 2 – twice the speed of sound, or a mile in less than three seconds – had not been easy, even if relatively straightforward(!). It was the little bit extra, needed for performance combined with safety, that was going to be difficult.

For some years previously this design team had been suffering from a creeping awareness that there was no way in which a huge stampede of horsepower, in hiccups, could escape from the wrong end of the Olympus engines without some bright beggar commenting on the fact.

Even in the massive engine test cells at Pyestock, the National Gas Turbine Engine Test Centre (NGTE) near Farnborough, the surges from a single engine had shaken the very foundations of the cathedral-like cells and left an uneasy impression of brute power on the rampage.

Happily, in the current phase of test flying no pieces of engine or bits of aircraft structure had become detached and headed for outer space. I suppose, they thought, we had better tell the pilots of that possibility too, before they find it out for themselves.

The nucleus of this group of engineers who had conceived the power plant had moved over the previous years from positions in various aerospace departments round an inevitable spiral to their respective places in the new Power Plant Group by secondment or adoption. In the Aerodynamics Office I had moved from project studies on wing shapes and the workings of the power plants and was put in this group with strict orders to defend them from the aerodynamicists and their demands for even thinner, stronger structures: the poacher had been turned gamekeeper. Within a short time Jim Wallin, with his comprehensive power plant experience of civil and military aircraft such as Viscount, Valiant, Vanguard and VC 10, arrived from Weybridge to become the Chief Power Plant Engineer as the workload grew quickly. As a man from Weybridge he professed to be pleasantly surprised at the warmth of his welcome in Filton. However, manning the increasing workload still remained a problem.

Like myself, David Moakes had been roped in from aerodynamics to pursue the practical development of the intake and its geometry, and inevitably this grew to include a heavy involvement in the development and in-service support of the rest of the nacelle, including the engine, nozzle and thrust reverser and associated systems.

Back in the Aerodynamics Office, the genius that was Terry Brown had blossomed in any field that he took an interest in. With his friend John Legg they became the principals in the diagnosis and definition of the brilliant solutions to the demands of flexibility, performance and compatibility between the engines and their intakes as demanded by a civil aircraft.

On a completely different, but equally essential, discipline, the wide experience of Tom Madgwick on Fire Precautions was also imported from Weybridge, due to the lack of background at Filton in the current civil field. Others, although not formally in the group, became ‘absorbed’ and were regarded by all disciplines as full members for the duration.

To complement the Technical Office there was a large Design Drawing, Systems and Stress Office coping with the new technology and the differences between the two prototypes and the individual differences of the two pre-production aircraft (see Appendix).

This was the team, which now specified, assessed, modified and integrated the efforts of the British and French aircraft and engine companies whilst designing an intake and its control system to cope with every normal and abnormal happening in flight.

Each member of the technical nucleus was a superb individual in his particular discipline who had earned, by dint of his efforts, the quiet respect of his fellows. This respect was derived from the fact that, without exception, each one had not only a profound understanding of their own particular subject, but could also give as much as they received in discussions with experts in other fields.

Within a few years they had become an entity second to none, as they later proved when American and Russian engineers failed to achieve overall success in the same area of expertise. Both Russian and American engineers were generous enough to express admiration for the feat, but, of course, their respective politicians did not. Neither did ours, unless prompted.

Almost everything was new and in advance of most things military.

‘Supercruise’ (long duration supersonic cruise without reheat) is not a recent invention. Concorde had to be doing it from the start. The early Tupolev Tu-144 didn’t incorporate it.

Fly-by-wire has only recently been adopted for civil airliners. Concorde had it from the start and it was carried on to its subsonic successors – versions of the Airbus series.

Electronic control systems for most engines are now the bee’s knees. The Bristol Siddeley Olympus introduced the first one into civil power plants fifty years ago. (The Bristol Britannia had simple electric controls from pilot to engines seventy years ago!)

Disc brakes on aircraft were first introduced by Dunlop on Concorde, firstly with metal pads and then with composite units. The list goes on.

The aircraft accumulated more hours at Mach 2 than the rest of the world’s air forces and will probably be unique for many years to come. Above all, Concorde is a thing of beauty, matched only by that gem of the thirties, the Spitfire.

Throughout the formative years of the project, and beyond, the designers were sustained by two common factors – a dry, Goon-like sense of the ridiculous, and a complete dedication to the project. The humour was worn as armour against incessant attacks on the British side from politicians, the press and trial by television ‘experts’. Most of these ‘experts’ in reality knew very little about the problems, but were actively trying to further their own or their questioners’ careers on the basis that the programme producers knew even less. I suggested to one producer who came to see me that she also talked to two more senior designers and the suggestion was summarily dismissed as they had already been interviewed ‘but talked like engineers!’

The team’s total dedication produced technical feats beyond even the normal expectations of intensive work projects when knocking on the doors of the frontiers of knowledge, but required no external pressures from any source to do so. The feat was still unmatched over forty years later in the civil or military fields.

It is unfortunate that in a project of this complexity it is difficult to pay tribute to everyone involved and my apologies go to that majority who are not mentioned.

The degree of dedication to the project was evident in the home life of those concerned, who, when with their families, found that their work was never very far from their thoughts. Honeymoons, holidays, weekends and evenings were planned or unplanned by it. Strange to relate, however, almost without exception their wives remained with their husbands, and the families appeared to be quite normal.

It is to these remarkable women, and to one in particular, that these stories are dedicated. This dedication is in the hope that, if they are still confused, it may bring some insight into the peculiar...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.9.2013 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Luftfahrt / Raumfahrt | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie | |

| Technik | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | aerodynamicist • aviation • aviation memoir • BAC • building aircraft • building planes • chief design engineer • Concord • Concorde • designing aircraft • MACH 2 • plane designer • ted talbot |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-9632-8 / 0752496328 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-9632-0 / 9780752496320 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich