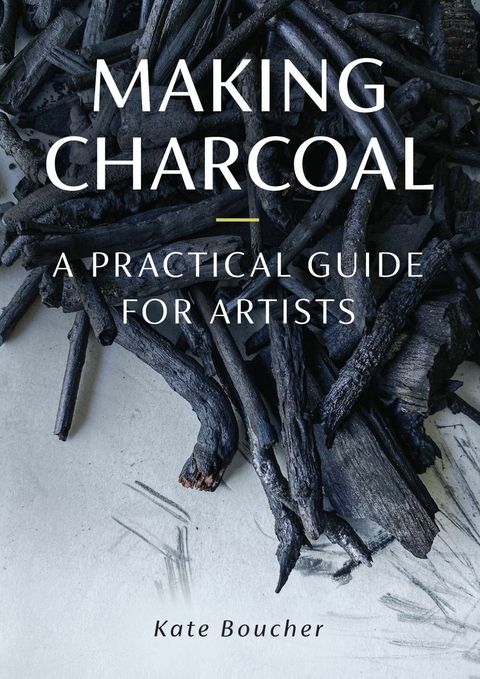

Making Charcoal (eBook)

112 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4407-2 (ISBN)

Kate Boucher is a professional artist who specialises in drawing the landscape with charcoal. She is a QEST scholar and has won numerous awards. She also teaches widely.

This practical book explains how to make charcoal using the simplest processes. Once understood, it encourages artists to experiment with the technique and to enjoy its unpredictable results. A sister title to Drawing with Charcoal, it will inspire artists and makers to look further into this sustainable material and to embrace its exciting potential.

CHAPTER 1

WHY MAKE YOUR OWN CHARCOAL?

Icould argue that there are many reasons to make your own charcoal: it’s inexpensive and sustainable, most of the materials are gathered for free, it needs only a few simple pieces of equipment, and it makes interesting and varied marks. The artist William Kendrick, when speaking about his use of charcoal, said:

A lot of artists in South Africa did drawing because it was cheap. You could find a scrap of paper and a ball-point pen, or a piece of charcoal and you could be an artist. You didn’t need an easel and stretchers and canvas and turpentine and expensive oil paint.

In addition to all this it can also give a sense of direct connection to the medium you’re using to make art with, because it’s in your hand – no mediation of the brush. Also, there’s a connection to the land that the charcoal came from, and the drawings that you’ll make from it. There is definitely something wonderful, and hard to define in the feelings you get when you open that tin and see charcoal you’ve made, and then the marks that that charcoal makes on paper.

Detail of a charcoal drawing on paper by Kate Boucher, with a piece of bramble (Rubus fruticosus) charcoal.

QUALITY CONTROL AND COURTING THE ACCIDENTAL

When I say ‘control’, I use the term loosely because one of the most interesting things about making your own charcoal to draw with, is the element of surprise inherent in using small-scale production methods and natural gathered materials with all their beautiful imperfections and quirky characteristics. But what you do have control of, is what materials to use, and what qualities these may give you in your drawings. You may not always get precisely the same result from the same method or plant, but you will always get something interesting.

In your work, this non-uniformity can be really exciting as you respond to the variability – a sort of collaboration with the material. The more charcoal you make, the more you will quickly develop the knowledge and skills needed to make more consistent batches of charcoal, especially if you use a limited range of plant material to start with, and test how best to char it to have the quality you want. I often find, though, that as I get more proficient, I like to push the process in some way, make it a little more difficult, or court the accidental to bring that element of surprise into the charcoal, and in turn, into my drawings.

Rotating this piece of charcoal shows how many different drawing ‘tools’ might be found from its facets. This piece, from a recent batch of common hazel (Corylus avellana), has an uneven surface with different parts of the wood exposed. The bark and core might give soft, velvety, light-toned or dense marks. Some areas will rub away easily, and others will grip the paper more, some have brown undertones, some very black ones.

On some species where the bark has been left on, the charcoal may be quite scratchy, which leaves beautiful etched-style grooves in the paper when you blend the loose powder in. You may not always want a scratchy mark though, which is why I test each piece in my sketchbook before using it on a drawing. You then have choices as to which facet (or piece) to use, or which to avoid.

beating the bounds, no.24 and no.27 by Kate Boucher. I use many different types of charcoal in my work, exploiting their qualities to render different elements in the photographs I’m working from. There are at least four types of plant in these two drawings, including bramble, hazel, birch and field maple. I’ve used bramble outer skin to make bold lines but scratchy marks, and birch over the top, which is very soft and smooth, sitting in the grooves made by the bramble.

The ground and tree were made using the piece of charcoal tested on the sketchbook page. The piece was turned, to find soft parts for smooth velvety marks, hard edges for linear marks, and scratchy areas to give texture. Just as you would select a different brush for the marks it will make, so you can select facets of a single piece of charcoal, or by selecting different pieces or species.

A work-in-progress by Benjamin Murphy: ‘I’m making the charcoal on a remote island in the middle of Finland’s largest lake. Silver birch is abundant but it’s not really the ideal wood for drawing charcoal, so I’m experimenting with different burn temperatures and durations to try and improve the quality. Currently it’s either too brittle or too shiny, and so the process of trial-and-error experimentation feels very much a part of the work as the drawing that will be the result of it.’

Benjamin Murphy’s birch charcoal being made in a metal tin ‘retort’. ‘It’s a slow and steady process, but it makes me feel much more connected to the work than when I use materials I had no hand in producing. The plan is also to make paper from the birch bark, and make artworks that are both of and from the island, and I look forward to getting started on that part of the process once I’ve perfected the charcoal.’

Benjamin Murphy, a visual artist and writer based between London and Helsinki, works with natural charcoal on raw canvas. He has moved from using commercially made willow and compressed charcoal to making his own from the silver birch (Betula pendula) that surrounds him on Lake Saimaa.

QUALITIES OF COLOUR AND TONE, AND EASE OF ERASING

When you use different types of plant material to make your own charcoal, you’ll begin to see how different they are from each other when you draw with them. Willow (Salix viminalis), the traditional wood for artist’s charcoal (and willow weaving), is a black with a silvery note, and can have a slight warm brown tone when blended. Alder (Alnus glutinosa) also has a silvery black tone and very fine texture. In fact, alder used to be used in gunpowder because it can be ground down so finely. Ivy has a little blueness to the colour, and can be scratchy and a little brittle. It has less scratchiness when you use dead rather than dried wood. Grape vine (Vitis vinifera) gives a rich black to dark grey. Older knuckles of vine can have their bark left on as this turns very soft and very black, almost like fine soft pastel. Raspberry canes (Rubus idaeus) have a brownish tone, and are very crumbly; they are good for adding large areas of tone. Thick blackberry stems (Rubus fruticosus) have a hard outer skin that gives fine black lines and an inner soft, powdery core that’s a light blown black.

These thick stems of blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) have dual qualities: the hard outer skin makes beautiful thin, crisp black lines that are hard to erase, which can allow the marks to stay visible as you build layers of marks. The inner core is light and powdery, with a rich brown tone that sits on the surface and can be brushed away and erased easily. These stems were charcoaled when still green and freshly cut.

This drawing, shown in sections, has been made with scratchy pieces of common ivy (Hedera) to create a foreground under-drawing of directional marks; soft, black grapevine (Vitis vinifera) bark for the flat, dark-toned areas layered on top; and small willow (Salix viminalis) sticks to add details. I’ve used a pure rubber eraser across the foreground and to add highlights: the variation in how it has erased is dependent on the type of charcoal it runs through, or lifts off.

though wishing slanting, no. 42, Kate Boucher. Hot press paper. The different woods used here, and the methods of pyrolyzing them, give slight variations in the colour, texture and tone. Some I’ve used for their fine hard edges that don’t erase easily, and some for their very black crumbliness, especially on the final layer to add texture. A drawing of a mixed wood, drawn with mixed woods!

All these species will erase differently, blend differently, and respond to paper surfaces differently. What you’ll be building as you make your own charcoal is a toolbox of variety, of non-uniform mark-making possibilities.

Sometimes the pieces of charcoal I make are so beautiful that they become like little sculptures. I’ve many pieces of interesting charcoal ‘too nice to use’, sitting on shelves around my house! They have also become plinths or components in sculptural work.

I get great pleasure from the pieces of charcoal displayed in my house. Some are over ten years old now, and I’ve moved twice in that time! They are memory prompts of where I collected the wood, or plant, where and why I made it, or who made it for or with me. Charcoal can be a beautiful thing, and before you know it, you too will have some ‘too nice to use’ bits sitting on a shelf somewhere!

LOOKING, GATHERING, AND PAYING ATTENTION

In some circumstances you might want to make charcoal from, and/or on, a specific place or landscape, and sometimes you might just want to make charcoal to draw with and it doesn’t need to have any connection to a place. Either way I would argue that the foraging for materials involves closer observation of your surroundings than you might otherwise give them. It may be that you’re searching for a certain species of wood, or that you’re looking with an open mind for something interesting that...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| Schlagworte | Artist • carbon • Carpenter • charcoal • Combustion • coppice • drawing • fire • firebowl • fixative • Greenwood • Illustration • Landscape • Pyrolysis • Tree • Willow • woodland • woodstove • Woodwork |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4407-X / 071984407X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4407-2 / 9780719844072 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 73,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich