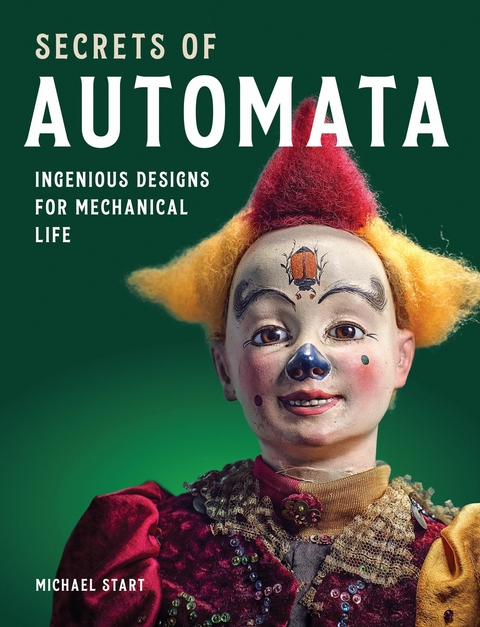

Secrets of Automata (eBook)

176 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4306-8 (ISBN)

Michael Start is a trained horologist who specialises in automata and mechanical singing bird restoration. Michael also runs The House of Automata in Forres, Scotland, a workshop, showroom and exhibition featuring a large number of rare automata. Once dubbed a 'clockwork guru' by the newspapers, he gives talks on and demonstrations of automata, provides consultancy and hire services to film and media, including Scorsese's Hugo and Hammer Films' The Woman in Black. He has also advised on and supplied automata to many major museums and collections around the world. Alongside his wife Maria, they feature their automata restoration skills on Quest TV in the series Salvage Hunters - The Restorers. The House of Automata has a significant social media presence promoting good restoration practice with knowledge and enjoyment of all things automata-related.

CHAPTER 1

MAKERS AND MECHANISMS

The aim of this book is to reveal mechanical secrets – the special mechanisms dedicated to a particular function and hidden from sight within the automaton. Most of these are innovations that have never been explained or published. This secrecy was necessary to preserve the livelihood and commercial advantage of the makers in what was a very competitive ‘high tech’ market.

Dancers in a Mirrored Grotto, Paris, c.1880. The secret of an automaton’s success can be as simple as a mirrored backdrop. These tiny dancing figures are multiplied by their own reflection, spinning and swirling so fast they are difficult to count. The musical scene is slowly revealed by the front garden folding down in front of the grotto – magical.

To understand the circumstances in which these mechanisms were invented and refined it will be useful to know a little of the history and to introduce some of the makers.

When looking back at the surprisingly long history of automata it is apparent that expertise in the subject usually resides in one country or region at a time, lasting for a century or more before fading away only to resurface again in a completely different place. This ‘passing of the baton’ between countries and civilisations is probably true for many subjects but is very evident over the 3,000-year history of mankind’s urge to make automata.

Each of these eras could probably be claimed as a ‘Golden Age’ of automata for different reasons but French automata of the nineteenth century stand out in technical, artistic and commercial terms. This book focuses on them in particular. I am helped by the sheer number of French automata that still exist in museums and private collections, many in working order, which allow me close examination when they come to my workshop for repair or restoration. For me to restore well, it is essential I research the automaton and understand its history. This is a part of the restoration process I particularly enjoy. In doing this I have become fascinated by particular makers and periods, but let us start at the beginning.

The Invention of Clockwork, c.1580, showing many of the processes and items of equipment that are needed to make geared mechanisms. The furnace that smelts the metal is shown close by, allowing recipes for brass and steel to be adjusted to suit the qualities required in the finished product in a much more direct way than is possible now.

(© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

AUTOMATA TIMELINE

This timeline shows how I see the western tradition of automata shifting over the centuries.

| 800BCE to 200CE | Greece and Italy |

| 800 to 1200 | Turkey and Iran |

| 1500 to 1700 | Germany |

| 1750 to 1830 | England and Switzerland |

| 1830 to 1930 | France |

| 1950 to present | USA and Europe |

THE MAKERS

The first automata

The first automaton is to be found whirring and clicking away in the classic texts of ancient mythology. As far back as 2,800 years ago, automatic moving machines performing human tasks are described by the Greek poet Homer. The ‘maker’ according to Homer was Hephaestus, son of Zeus, who served as blacksmith to the Gods. Hephaestus (or Vulcan in the Roman tradition) made various life-sized automata to labour in his workshop working the bellows and forge. For the celestial hall of the Gods he made twenty golden tripod servants that trundled about on wheels. He also created an elaborate golden throne for his estranged mother which deliberately entrapped her, presumably mechanically, the moment she sat on it.

The automaton maker can look up to their own deity, the Greek God of fire and forge, Hephaestus. His ability to make mechanical automata was demonstrated in many of the myths of ancient Greece. Here he poses with his hammer and tongs, with the magical armour of Achilles at his feet. The statue is by the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen.

(PHOTO: JAKOB FAURVIG, THORVALDSENS MUSEUM PD)

Of the many devices that could be described as automata in mythology, most have some divine or magical aspect to their creation or operation. Magic aside, the main reasons for creating them were for utility purposes like mechanical serving machines and death-proof armour.

The Antikythera mechanism is the earliest known geared machine. Dating from around 200BCE, the device was found in a Roman era shipwreck near the island of Antikythera. Corroded and fragmented, it is the perfect combination of age and ambiguity. These qualities continue to excite scientists and theoreticians who work with the certainty that this mystical machine must have done something.

(TILEMAHOS EFTHIMIADIS, ATHENS, CC BY 2.0)

It is the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism, a scientific instrument dating to perhaps 200BCE, which provides us with the first example of a real mechanism to start our discovery of mechanical automata. Brought up from the seabed in 1902 as a corroded green metal blob about the size of a large cake, over time it has been ‘conserved’ into eighty-three separate pieces revealing several gears, the largest 5.1 inches in diameter with (perhaps) 223 teeth. It is generally thought to be a machine to predict astronomical events, a sort of analogue computer.

The Grotto, 1615. In the seventeenth century Heron of Alexandria’s newly reissued first-century work Pneumatica inspired Salomon de Caus in this design for a water grotto. Galatea, a sea nymph, rides to and fro on the surface of the water, powered by a water wheel, while music plays. Water gardens with automata were popular across Europe at this time.

(PHOTO: THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK, CC0 1.0)

The first technically viable theoretical automata of which we have a more complete knowledge are the work of Heron of Alexandria. Heron was a mathematician and engineer who was active around 60CE. Heron’s many designs for automated temples and figures were described and illustrated in his works Pneumatica, Automata and Mechanica.

For the next 1,000 years automata makers are quite sparse in the history books although the odd explorer and traveller does come across them and write about the experience. This is how we know that in 835CE the Byzantine Emperor Theophilos had a throne made, flanked by mechanical lions which roared and were shaded by a golden tree filled with mechanical singing birds. He was probably competing with the Caliph Abd-Allah-Al-Mamun in Baghdad, whose mechanical birds sang beautifully on a silver tree, reported in 827CE.

Jack the Smiter, fifteenth century, St Edmund’s Church, Southwold. This Jack is (unusually) not connected to a clock but is used to announce services and weddings in this English church. For most people their only experience of automata would be in places of power like the church where clocks might feature quite complex parades of automata to announce the hours.

(PHOTO: ANDREWRABBOTT, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The next big moment for automata comes from Mesopotamia in 1206 when Ismail al-Jazari compiled his Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Known as the al-Jazari manuscripts, these collate existing knowledge and add new designs for automaton water clocks, fountains and devotional machines. All these inventions pre-date the advent of true clockwork whose birth is about to take place in the steeples, spires and homes of the rich across fourteenth-century Europe. This early clockwork often incorporated the ringing of bells as most people could not tell the time from a dial. What better way of ringing a bell can there be, than by having a mechanical man hit it with a hammer?

Augsburg

The gold and silversmiths of Augsburg (Germany) in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were making beautiful mechanical automata for export around the world. The automata were extravagant table ornaments in the form of animals, mythological figures and silver model ships called Nefs. Some Nefs were animated to ‘sail’ down the banquet table on eccentric wheels while a small band paraded on deck playing music. The ship would then stop and fire its cannons.

The Lion Rampant, an automaton clock, German c.1630. The lion moves its eyes continuously and opens and closes its mouth at each strike of the hour bell. A large number of animal automata clocks were made in Augsburg in the seventeenth century; subjects read like a Disney parade of bears, camels, dogs, monkeys and elephants, full of exaggerated character.

(PHOTO: THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK, CC0 1.0)

The clockwork automata made in Augsburg are rare treasures and most of the remaining examples are to be found in museums today. Almost totally handmade, these refined and complex mechanisms were not at all crude, despite the early date for spring-powered clockwork. They are high value masterpieces created to affirm their global dominance in the making of fine mechanism at this time.

London

From 1750 to 1850 the centres of mechanical automata production had shifted to London and Geneva. During this period in Switzerland the father and son makers Pierre and Henri Jaquet-Droz were producing incredibly complex animated figure automata. The most famous of these are the three ‘androids’ – the Writer, the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Antiquitäten |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Kreatives Gestalten | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Sammeln / Sammlerkataloge | |

| Schlagworte | Android • animatronic • Antique • Artificial Intelligence • Automata • Automaton • Clockwork • Collecting • Diorama • horology • kinetic • Magic • makers • Mechanism • Miniatures • Modelmaking • restoration • robot • Watches |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4306-5 / 0719843065 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4306-8 / 9780719843068 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 77,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich