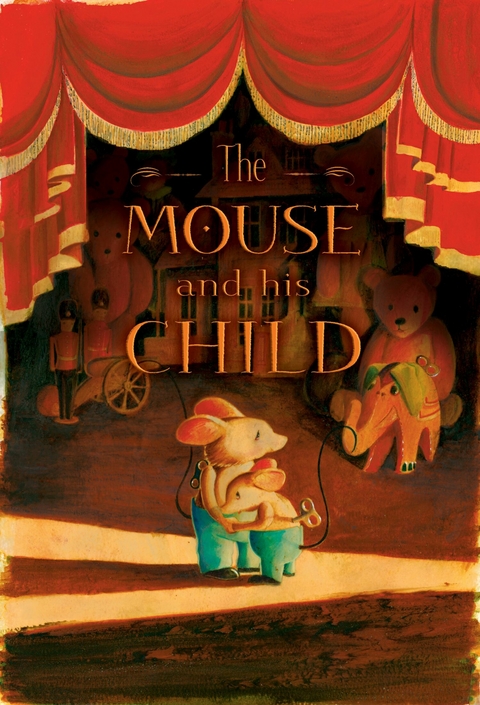

Mouse and His Child (eBook)

176 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-29844-0 (ISBN)

Russell Hoban was born in Pennsylvania in 1925. He went to art school before serving in World War II and was a freelance illustrator for eight years before taking up full-time writing. His many works of fiction and poetry for both adults and children have won him numerous awards. The Mouse and His Child has been hailed as one of the great classics of the twentieth century.

Funny, thought-provoking and moving, this much loved story is a true classic. 'What are we, Papa?' the toy mouse child asked his father. 'I don't know,' the father answered. 'We must wait and see.'So begins the story of a tin father and son who dance under a Christmas tree until they break the ancient clockwork rules and are themselves broken. Thrown away, then rescued from a dustbin and repaired by a tramp, they set out on a dangerous quest for a family and a place of their own - the magnificent doll's house, the plush elephant and the tin seal they had once know in the toy shop. 'Hugely funny, provocative, pathetic and heroic.' TLS'Brilliantly plotted . . . a spellbinder . . . it has a style that glows and crackles.'Spectator

Russell Hoban was born in Pennsylvania in 1925. He went to art school before serving in World War II and was a freelance illustrator eight years before taking up full-time writing. His many works of fiction and poetry for both adults and children have won him many awards. The Mouse and his Child has been hailed as one of the great children's classics of the twentieth century.

The tramp was big and squarely built, and he walked with the rolling stride of the long road, his steps too big for the little streets of the little town. Shivering in his thin coat, he passed aimlessly through the crowd while rosy-faced Christmas shoppers quickened their steps and moved aside to give him room.

The sound of music made him stop at a toyshop where the door, continually swinging open and shut in a moving stream of people, jangled its bell and sent warm air and Christmas carols out into the street. ‘Deck the halls with boughs of holly,’ sang the loudspeakers in the shop, and the tramp smelled Christmas in the pine wreaths, in the bright paint and varnish, in the shining metal and fresh pasteboard of the new toys.

He put his face close to the window, and looking past the toys displayed there, peered into the shop. Under the wreaths and winking coloured lights a little train clattered through sparkling tunnels and over painted mountains on a green table, the tiny clacking of its wheels circling in and out of the music. Beyond it the shelves were packed with tin toys and wooden toys and plush toys – dolls, teddy bears, games and puzzles, fire engines and boats and wagons, and row on row of closed boxes, each printed with a fascinating picture of the toy it hid from sight.

On the counter, rising grandly above the heads of the children clustered before it, was a splendid dolls’ house. It was very large and expensive, a full three stories high, and a marvel of its kind. The porches and balconies were elegant with scrollwork brackets, and the mansard roof with its dormers and cross gables was topped by tall brick chimneys and a handsome lookout. In front of the house stood a clockwork elephant wearing a purple headcloth, and when the saleslady wound her up for the watching children, she walked slowly up and down, swinging her trunk and flapping her ears. Near the elephant a little tin seal balanced a red and yellow ball on her nose and kept it spinning while her reflection in the glass counter top smiled up at her and spun its own red and yellow ball.

As the tramp watched, the saleslady opened a box and took out two toy mice, a large one and a small one, who stood upright with outstretched arms and joined hands. They wore blue velveteen trousers and patent leather shoes, and they had glass-bead eyes, white thread whiskers, and black rubber tails. When the saleslady wound the key in the mouse father’s back he danced in a circle, swinging his little son up off the counter and down again while the children laughed and reached out to touch them. Around and around they danced gravely, and more and more slowly as the spring unwound, until the mouse father came to a stop holding the child high in his upraised arms.

The saleslady, looking up as she wound the toy again, saw the tramp’s whiskered, staring, face on the other side of the glass. She pursed her mouth and looked away, and the tramp turned from the window back to the street. The gray sky had begun to let down its snow, and the ragged man stood in the middle of the pavement while the soft flakes fell around him and the people quick-stepped past him.

Then, with his big broken shoes printing his footsteps in the fresh snow, he solemnly danced in a circle, swinging his empty arms up and down. A little black-and-white spotted dog trotting past stopped and sat down to look at him, and for a moment the man and the dog were the only two creatures on the street not moving in a fixed direction. People laughed, shook their heads, and hurried on. The tramp stopped with arms upraised. Then he lowered his head, jammed his hands into his pockets, and lurched away down the street, around a corner, and into the evening and the lamplight on the snow. The dog sniffed at his footprints, then trotted on where they led.

The store closed. The customers and clerks went home. The music was silent. The wreaths were dim, the shop was dark except for the dolls’ house on the counter. Light streamed from all its windows out into the shadows around it, and the toys before it stood up silhouetted black and motionless as the hours slowly passed.

Then, ‘Midnight!’ said the old store clock. Its pendulum swung gleaming in the shadows as it counted twelve thin chimes into the silence, folded its hands together, and stared out through the dark window at the thick snow sifting through the light of the street lamp. Far away and muffled by the snow the town hall clock struck midnight with its deeper note.

‘Where are we?’ the mouse child asked his father. His voice was tiny in the stillness of the night.

‘I don’t know,’ the father answered.

‘What are we, Papa?’

‘I don’t know. We must wait and see.’

‘What astonishing ignorance!’ said the clockwork elephant. ‘But of course you’re new. I’ve been here such a long time that I’d forgotten how it was. Now, then,’ she said, ‘this place is a toyshop, and you are toy mice. People are going to come and buy you for children, because it’s almost a time called Christmas.’

‘Why haven’t they bought you?’ asked the little tin seal. ‘How come you’ve stayed here so long?’

‘It isn’t quite the same for me, my dear,’ replied the elephant. ‘I’m part of the establishment, you see, and this is my house.’

The house was certainly grand enough for her, or indeed for anyone. The very cornices and carven brackets bespoke a residence of dignity and style, and the dolls never set foot outside it. They had no need to; everything they could possibly want was there, from the covered platters and silver chafing dishes on the sideboard to the ebony grand piano among the potted ferns in the conservatory. No expense had been spared, and no detail was wanting. The house had rooms for every purpose, all opulently furnished and appropriately occupied: there were a piano-teacher doll and a young-lady-pupil doll in the conservatory, a nursemaid doll for the children dolls in the nursery, and a cook and butler doll in the kitchen. Interminable-weekend-guest dolls lay in all the guest room beds, sporting dolls played billiards in the billiard room, and a scholar doll in the library never ceased perusal of the book he held, although he kept in touch with the world by the hand he lightly rested on the globe that stood beside him. There was even an astronomer doll in the lookout observatory, who tirelessly aimed his little telescope at one of the automatic fire sprinklers in the ceiling of the shop. In the dining room, beneath a glittering chandelier, a party of lady and gentleman dolls sat perpetually around a table. Whatever the cook and butler might hope to serve them, they had never taken anything but tea, and that from empty cups, while plaster cakes and pastry, defying time, stood by the silver teapot on the white damask cloth.

It was the elephant’s constant delight to watch that tea party through the window, and as the hostess she took great pride in the quality of her hospitality. ‘Have another cup of tea,’ she said to one of the ladies. ‘Try a little pastry.’

‘HIGH-SOCIETY SCANDAL, changing to cloudy, with a possibility of BARGAINS GALORE!’ replied the lady. Her papier-mâché head being made of paste and newsprint, she always spoke in scraps of news and advertising, in whatever order they came to mind.

‘Bucket seats,’ remarked the gentleman next to her. ‘Power steering optional. GOVERNMENT FALLS.’

The mouse child was still thinking of what the elephant had said before. ‘What happens when they buy you?’ he asked her.

‘That, of course, is outside of my experience,’ said the elephant, ‘but I should think that one simply goes out into the world and does whatever one does. One dances or balances a ball, as the case may be.’

The child remembered the bitter wind that had blown in through the door, and the great staring face of the tramp at the window with the gray winter sky behind him. Now that sky was a silent darkness beyond the street lamp and the white flakes falling. The dolls’ house was bright and warm; the teapot gleamed upon the dazzling cloth. ‘I don’t want to go out into the world,’ he said.

‘Obviously the child isn’t properly brought up,’ said the elephant to the gentleman doll nearest her. ‘But then how could he be, poor thing, without a mother’s guidance?’

‘PRICES SLASHED,’ said the gentleman. ‘EVERYTHING MUST GO.’

‘You’re quite right,’ said the elephant. ‘Everything must, in one way or another, go. One does what one is wound to do. It is expected of me that I walk up and down in front of my house; it is expected of you that you drink tea. And it is expected of this young mouse that he go out into the world with his father and dance in a circle.’

‘But I don’t want to,’ said the mouse child, and he began to cry. It was an odd, little, tinny, rasping, sound, and father and son both rattled with it.

‘There, there,’ said the father, ‘don’t cry. Please don’t.’ Toys all around the shop were listening. ‘He’d better stop that,’ they said.

It was the clock that spoke next, startling them with his flat brass voice. ‘I might remind you of the rules of clockwork,’ he said. ‘No talking before midnight and after dawn, and no crying on the job.’

‘He’s not on the job,’ said the seal. ‘We’re on our own time now.’

‘Toys that cry on their own time sometimes cry on the job,’ said the clock, ‘and no good ever comes of it. A word to the wise.’

‘Do be quiet,’ said the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.9.2012 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kinder- / Jugendbuch ► Jugendbücher ab 12 Jahre |

| Kinder- / Jugendbuch ► Kinderbücher bis 11 Jahre | |

| Schlagworte | animals • Fairytales • Families • Friendship • mice • Toys |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-29844-3 / 0571298443 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-29844-0 / 9780571298440 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 16,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich