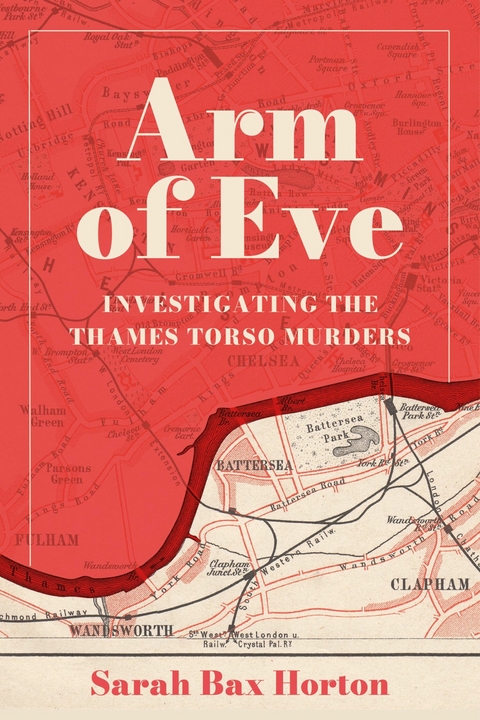

Arm of Eve (eBook)

288 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-749-0 (ISBN)

SARAH BAX HORTON is an experienced former civil servant for the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. She has an MA Honours degree in English and Foreign Languages (German) from Somerville College, Oxford. She is the author of One-Armed Jack (Michael O'Mara, 2023).

Sarah Bax Horton is an experienced former civil servant for the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. She has an MA Honours degree in English and Foreign Languages (German) from Somerville College, Oxford. She is the author of One-Armed Jack (Michael O'Mara, 2023).

Introduction

The Thames Torso Killer should, by rights, take precedence over Jack the Ripper as the world’s first unidentified modern serial killer. He started to kill in early 1887, over a year before the Ripper, and his last murder was in autumn 1889, almost ten months after that of the Ripper’s last victim, Mary Jane Kelly. The Torso Killer murdered and dismembered at least four women, in addition to the unborn child of the only victim who was identified. The police surgeons of the day pieced together the headless remains and provided best-guess descriptions of each woman, while Metropolitan Police officers worked through lists of missing persons. Despite their best endeavours, all but one went nameless to their graves. This book is named Arm of Eve after a sketch by Albrecht Dürer of Eve’s idealised left arm, its hand curled around the forbidden apple, representing the universal woman.

The Metropolitan Police Whitechapel Murders files cover the deaths of eleven women between 1888 and 1891. Those women were similar to each other in their destitution and dependence on street-hawking and soliciting. At least five were casual sex workers killed by Jack the Ripper: Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elisabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly. A sixth, Martha Tabram, was probably the Ripper’s first kill. Emma Smith, who died twenty-four hours after being attacked, said she was assaulted by a gang of men. Scotland Yard assessed Rose Mylett’s demise to be an accident. The murders of street walkers Alice Kinsey, or McKenzie, and Frances Coles also remained unsolved. Some commentators add Kinsey to the canon of women killed by Jack the Ripper, as her abdominal injuries were similar to the type of posthumous mutilations which he inflicted for his own gratification.

One of the last murders on those files was that of an unidentified woman referred to as the Pinchin Street trunk, whose dismembered torso was discovered under an East End railway arch. Like the other cases, it has long been considered a possible Ripper crime. But the Pinchin Street victim was killed by the Thames Torso Killer. The police of the day classified it as such, attributing it to a second serial killer active at the same time who was believed to have committed four murders. While the Ripper killed between August and November 1888, the Torso Killer started his attacks in April 1887 and probably stopped after the Pinchin Street murder in September 1889.

Extraordinarily, the Torso Killer operated at the same place and time as the Ripper, with whom he shared notable similarities. Like the Ripper, this killer picked his victims through chance sightings of women who fitted his ideal victim type. Mostly dark-haired and busty, they were of a similar age to his wife, and happened to be alone when he spotted them. A few of them, low on funds, might have occasionally sold their bodies for sex. Unlike the Ripper, who did not sexually assault his victims, the Torso Killer was a rapist turned killer; his approach based on the classic rapist’s mantra: isolate – inebriate – penetrate. His frustration with women manifested itself through violence, gaining control through brute force. It is clear from their injuries that his victims put up a vigorous defence. He was brutal, physical, under-educated, clever enough to develop a repeatable crime, but not so intelligent to grasp that his methods created a pattern that could be deciphered.

Unlike his notorious counterpart, the Torso Killer did not simply abandon his victims’ bodies. He cut them up and deposited the pieces at locations around Central London; not only in the River Thames and Regent’s Canal, but also in Battersea Park, a private garden, under a railway arch and, notably, in the foundations of New Scotland Yard. Mutilation and dismemberment are two distinct ‘signatures’ of murder. The Ripper’s primary objective was to open his victims’ abdomens and remove their organs. In extreme cases, he cut their faces and other body parts. The Torso Killer dismembered his victims’ bodies, both for gratification and disposal. This difference alone is sufficiently significant to indicate not one, but two serial killers, as defined by the police of the day.

The four murders typically attributed to the Torso Killer occurred in close sequence and are named after locations where body parts were found: Rainham in May 1887; Whitehall in September 1888, at the first peak of the Ripper scare; Battersea and Pinchin Street in 1889. The police surgeons of the day used scientific techniques to deduce the age, height and defining characteristics of each woman, while Scotland Yard’s Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and divisional police officers appealed for information from the public to make a match. Only the ‘Battersea’ victim was ever identified, a pregnant 24-year-old from Chelsea named Elizabeth Jackson, demonstrating that the historical names were misnomers. They do not represent the locations where each woman was accosted or killed, frustrating the police investigation. As in any murder series, each subsequent case reveals something new about its perpetrator and confirms something consistent in his operational method.

The Metropolitan Police District covered a 15-mile radius of Charing Cross and was divided into four districts, sub-divided into divisions. Police from up to a dozen divisions investigated the Torso cases, reflecting the diverse locations where body parts were found. Ripper veterans from Whitechapel’s H Division worked on the Pinchin Street murder, as did divisional police surgeons led by early forensic expert Mr Thomas Bond and his assistant at Westminster Hospital, Doctor Charles Hebbert. Bond was the real powerhouse of the duo, being ‘probably the expert of his day, esteemed by his colleagues, often brought in when other medical evidence was in dispute’.1 Both men were also involved in the Ripper post-mortems, notably that of Mary Jane Kelly, after which Bond produced the world’s first profile of a serial killer.

The senior police officers involved in the Torso investigations also had Ripper experience. They included Metropolitan Police Commissioners Sir Charles Warren and his successor James Monro, CID Chiefs Robert Anderson and Melville ‘Mac’ Macnaghten, Chief Constable Colonel Bolton Monsell, H Division Superintendent Thomas Arnold, Chief Inspectors Henry Moore and John West, Detective Inspectors Donald Swanson, Frederick Abberline and John Shore, and Inspectors Charles Pinhorn and Edmund Reid. The author’s great-great-grandfather Harry Garrett was an H Division sergeant based at Leman Street police station, and was previously a constable in Greenwich’s R Division. Like his seniors, he worked in some capacity on the Ripper murders, as did Detective Sergeant Frank Froest, who was directly involved in the Pinchin Street Torso case owing to its East End location.

Several more police surgeons and officials were involved in both the Thames Torso and the Whitechapel Murders investigations. Doctor George Bagster Phillips, a stalwart of the Ripper case, was called out alongside his assistant Doctor Percy Clark, as was Doctor Frederick Gordon Brown, the City Police surgeon who had conducted the post-mortem examination of Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes. And one of the coroners was, again, Wynne Edwin Baxter.

The officers of Thames Division, the river police, were instrumental in bringing my proposed perpetrator of the Thames Torso Murders to an approximation of justice. The river police force numbered 200 men, with a chief inspector, seven inspectors, forty sub-inspectors, five detectives and 147 constables. Policemen patrolled the Thames in six-hour shifts, using twenty rowing boats and two steam launches.2 Their headquarters was at Wapping, in a building still in use today, although in this instance their police station at Waterloo Bridge was the scene of the action.

In ensuring the conviction of this perpetrator, Detective Inspector John Regan drew on his considerable local knowledge of the river’s smugglers, thieves and miscreants. Described in police records as precisely 5ft 6⅜ inches tall, with blue eyes and greying hair, Regan was born just north of the river in St George-in-the-East. A year older than my police ancestor Harry Garrett, he was his contemporary and, in 1891, his near-neighbour on Stepney’s Oxford Street, today’s Stepney Way.

A key document for any researcher into the Thames Torso Murders is a report in two parts written by Doctor Charles Hebbert with input from his senior colleague Bond. The report was compiled from lecture notes for students of forensic science, and was prefaced as being for their future guidance, should they be required to report the results of a post-mortem examination to the authorities:

When a medical man is called upon by the coroner or the police to examine such cases, he often is at a loss to know how much or how little to report, so in the following pages I have indicated the usual procedure, hoping that they may interest some students of forensic medicine, and perhaps aid them in framing a report if ever they are requested to make one.3

In it, Hebbert demonstrated how the post-mortem examination of a murder victim could assist in identifying the body, where possible state the cause of death, and deduce characteristics about the victim and perpetrator to direct the police investigation.

The Hebbert report definitively unites the four crimes committed in the period 1887–89:

The mode of dismemberment and mutilation was in all similar, and showed very considerable skill in execution, and it is a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | 1887 • 1888 • 1889 • 19th century murderer • battersea • Bedford Square Mystery • detective inspector john regan • Elizabeth Jackson • Jack the Ripper • james crick • New Scotland Yard • pinchin street • rainham mystery • serial killer • Thames Torso Killer • Thames Torso murders • Tottenham Court Road Mystery • victorian crime • victorian prostitute • Victorian True Crime • whitehall mystery |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-749-4 / 1803997494 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-749-0 / 9781803997490 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich