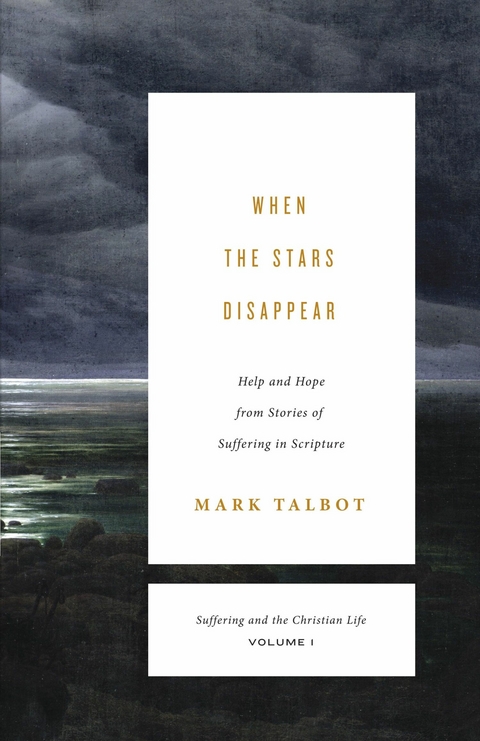

When the Stars Disappear (Suffering and the Christian Life, Volume 1) (eBook)

144 Seiten

Crossway (Verlag)

978-1-4335-3353-2 (ISBN)

Mark Talbot (PhD, University of Pennsylvania) is an associate professor of philosophy at Wheaton College and the host of the When the Stars Disappear podcast. He is also the author of the Suffering and the Christian Life series, including When the Stars Disappear and Give Me Understanding That I May Live. He and his wife, Cindy, have one daughter and three grandchildren.

Mark Talbot (PhD, University of Pennsylvania) is an associate professor of philosophy at Wheaton College and the host of the When the Stars Disappear podcast. He is also the author of the Suffering and the Christian Life series, including When the Stars Disappear and Give Me Understanding That I May Live. He and his wife, Cindy, have one daughter and three grandchildren.

1

Man who is born of a woman is few of days and full of trouble.

Job 14:1

Here on earth you will have many trials and sorrows.

John 16:33 (NLT)

The telephone rang about nine on a Sunday morning while we were getting ready for church. I heard the answering machine pick up. As we headed for the garage, I hit the “Play” button. A familiar voice said, “Dr. Talbot, this is Graham. Are you there?”1 After a couple of seconds of waiting, I heard him say, “Hmm,” and then hang up.

It was September. Graham had graduated from Wheaton College in May and then headed overseas for some graduate study in philosophy. He became a philosophy major after taking one of my introductory courses in the fall of his freshman year. We had talked a lot that year. I was encouraged by the depth of his Christian commitment, cheered by his quick humor, and pleased with his sharp, active mind.

For a couple of years after that class, we lost contact. Then I bumped into him at the start of the last term of his final year. He said he would really like to talk. Over lunch he described the depression that had dogged him for years. He had begged God to lift it. But nothing had changed. And so now he was tired, deeply depressed, and uncertain. How could he believe that Christianity was true if God hadn’t answered his desperate prayers?

We arranged to talk regularly. He told me he had been in counseling for several years. I had known other chronically depressed students, so I knew how profound their suffering could be. He was grateful when I offered to talk with his parents, which I started doing right away.

Often when I’m dealing with depressed and potentially suicidal students, I ask them to promise they will try to call me at any time, night or day, if they are desperate. Graham had promised, but that Sunday morning he hadn’t sounded distressed. After listening to his voice message, I found myself thinking perhaps he was back in the States temporarily and just wanted to get together for lunch.

Monday afternoon I came home from a meeting to find another message, this one from Graham’s father. They had received word that Graham had been killed when he was hit by a train. I called them. They had tried to reach the proper authorities, but they hadn’t yet been able to learn anything more. I kept my fears to myself. But when I got home the next day, Graham’s dad had left another message: it seemed clear Graham’s death was a suicide.

As I pieced it together, it became clear that Graham had kept his promise. He had called me less than an hour before he stepped in front of the train.

Calamitous Suffering

Profound suffering involves experiencing something so deep and disruptive that it dominates our consciousness and threatens to overwhelm us, often tempting us to lose hope that our lives can ever be good again. A calamity is “an extraordinarily grave event marked by great loss and lasting distress and affliction.”1 Both calamities (such as losing a child to suicide) and chronic conditions (such as the continuous care of a severely disabled child or Graham’s seemingly never-ending struggle with depression) can produce profound suffering.

Graham’s death has been a calamity. Calamities, like earthquakes, start in cores of tragedy that have waves of suffering radiating out from them. For onlookers, the sufferers’ lives may soon seem fairly normal again. But for the sufferers themselves, there may be deep inner fault lines that outline shattered faith. The upheavals involved can be so great that it can seem that life can never be good again.

These fault lines often reveal themselves in a series of insistent, unanswered questions. Graham’s parents keep asking these:

How could God allow this to happen to our son? We know God is all-powerful and governs everything, so why didn’t he alter this course of events?

As Christians we have always believed God is our heavenly Father who answers believing prayer. Yet we prayed believing God would help Graham overcome his depression, so why didn’t God help him?

And why did God afflict our son with this burden in the first place, especially since he, as all-knowing, was always aware it would end in Graham’s death?

“Why,” they ask, “didn’t God arrange things so that at least one of the three people whom Graham tried to call in his last hour would have answered the telephone and perhaps helped him find the strength to live another day?”

This book began in response to this calamity. When we stand alongside suffering believers, we face our own questions. In this case, I have asked myself repeatedly, Could I have helped Graham more? Could I have said anything to him that would have made his life more bearable? Were there ways I could have helped him see that God was with him in his dark times even though God didn’t take the darkness away? And how can I now comfort his parents? Are there ways to help them weather their profoundly disorienting grief?

Such a calamity reveals how little most of us have thought about what we should say or do in circumstances like these. Does profound suffering have phases that make different responses appropriate at different times? Does intense grief have an early phase when we shouldn’t say much, and the best we can do is pray that God will help his grieving children keep their faith? Is it ever appropriate to tell sufferers what many of us have learned through our own suffering, which is that a day will come when they will again feel some peace in spite of their calamity? Should we encourage them to believe they will someday receive satisfying answers to all of their questions? And what should we say to nonbelievers? Is God in some way being good to them in their suffering?

This Vale of Tears

I will address these questions as we proceed. But no matter how they are answered, all Christians need to come to grips with the potential breadth and depth of what we may suffer. Scripture does not encourage us to believe our lives will be pain free. It shows God’s people have always suffered. We can feel profound, life-depleting sorrow.

In Scripture, proper names are meaningful. And so it is significant that even David, whose very name means “beloved by God,”2 could cry,

Be gracious to me, O Lord, for I am in distress;

my eye is wasted from grief;

my soul and my body also.

For my life is spent with sorrow,

and my years with sighing;

my strength fails . . . ,

and my bones waste away. (Ps. 31:9–10)

As Job observed, suffering is a regular part of human life (see Job 14:1), though it comes in different kinds and degrees. Graham’s parents have undergone an almost inconceivable calamity, but not all suffering involves experiencing hurts so deep and disruptive that their presence dominates our lives, and even deep and disruptive suffering may not shake our faith. Yet, as Henri Blocher observes, suffering often presents us with a problem in the original sense of that word—that is, it throws an obstacle across our paths, “something that blocks our view, for it resists our . . . efforts to understand it.”3 So we shouldn’t be alarmed or frightened to find ourselves perplexed when we suffer. Suffering often does perplex us, although (as we shall see in chapter 4) this shouldn’t surprise God’s people.

Readers of the books of Ruth and Job know that God’s Old Testament saints sometimes suffered calamitously, just as readers of the Psalms and Jeremiah know that some suffered chronically. And in spite of some Christian teachers’ claims to the contrary, we shouldn’t expect it will be different for us as God’s New Testament people.4 For we are part of the creation that has been subjected to futility and that groans for its redemption (see Rom. 8:18–25). Hebrews also tells us that God may use suffering to discipline us for our good (see Heb. 12:3–11).

We are also called to suffer for Christ’s name (see, e.g., 2 Tim. 1:8 and 2:3 with Phil. 1:29). “Here on earth,” our Lord told his disciples in his farewell discourse to them in John’s Gospel, “you will have many trials and sorrows” (John 16:33 NLT). The apostle Paul opened 2 Corinthians by observing that he and Timothy were sharing abundantly in Christ’s sufferings (see 1:5). Their suffering had in fact been so terrible that they had “despaired of life itself,” feeling they “had received the sentence of death” (1:8–9). No wonder Paul declared, “If in Christ we have hope in this life only, we are of all people most to be pitied” (1 Cor. 15:19).

So we Christians should not be surprised if we suffer just as much or even more than non-Christians, since we may suffer in virtually any of the ways anyone can suffer, and we will also suffer more specifically as Christians.

My Story

When I was seventeen, I fell about 50 feet off a Tarzan-like rope swing, breaking my back and becoming partially paralyzed from the waist down. I spent six months in hospitals. Initially, I had no feeling...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.8.2020 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Suffering and the Christian Life |

| Verlagsort | Wheaton |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik |

| Schlagworte | Arminian • Bible study • Biblical • Calvinist • Christ • Christian Books • Church Fathers • Doctrine • Faith • God • Gospel • hermeneutics • Prayer • Reformed • Systematic Theology • Theologian |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4335-3353-7 / 1433533537 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4335-3353-2 / 9781433533532 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 458 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich