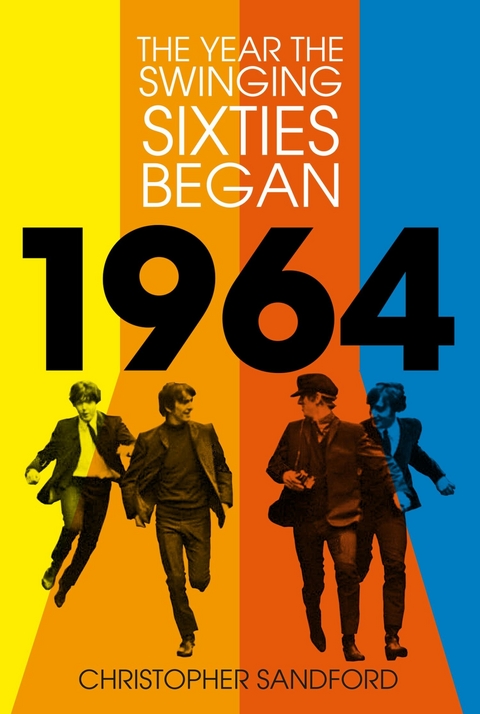

1964 (eBook)

288 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-601-1 (ISBN)

CHRISTOPHER SANDFORD is a regular contributor to newspapers and magazines on both sides of the Atlantic. He has written numerous biographies of music, film and sports stars, as well as Union Jack, a bestselling book on John F. Kennedy's special relationship with Great Britain described by the National Review as 'political history of a high order - the Kennedy book to beat'. Born and raised in England, Christopher currently lives in Seattle.

INTRODUCTION

ALL OUR YESTERDAYS

I spent most of 1964 as a 7-year-old schoolchild in an unprepossessing ghetto of south London, amid bricks and soot and cratered streets, where milk bottles, which sometimes spontaneously exploded in the cold, were delivered each morning by a man in an apron riding a horse-drawn cart. My mother went to the shops almost every day, not because we were gluttons but because our fridge was roughly the size of a small suitcase and we lacked a freezer. Our local grocery store, which went by the perhaps leading name of Mr Crooke’s, was staffed by two or three middle-aged men also in aprons, had sawdust on the floor and closed early each Thursday. For Sunday lunch we generally treated ourselves to a joint of Mr Crooke’s sweaty pink beef accompanied by a salad soaked in a brown oil that doubled as earwax remover. Our house was a poorly ventilated semi with postage-stamp-sized rooms patched together by crumbling plaster walls, although we aspired to that era’s defining domestic status symbol of full indoor plumbing. ‘Bloody lucky, too,’ my father, then a landbound navy officer, remarked. The hint of amused irony behind the genuine conviction that we could have been much worse off was unmistakable.

Each weekday morning my father caught a commuter train for its last couple of stops into Waterloo, an experience he rarely spoke of fondly, and then walked over the bridge to his desk job in the Stalinist-looking bulk of the Ministry of Defence. A long-running power dispute involving the Amalgamated Engineering Union and their demand for a maximum forty-hour week periodically plunged all the houses in our street into total darkness, and when this happened we sat around in unheated rooms, the TV set – which, reversing the formula of the fridge, was the size of a coffin – shut off, reading flimsily printed newspapers by candlelight. My school classroom, about a mile away, included a pot-bellied stove and a row of wooden desks with a communal inkwell, into which we dipped our blue Osmiroid nibs. There was a framed official portrait of a youthful-looking Queen on the wall. The water emerged from the school’s bathroom taps, to a cacophony of clanking pipes, with the consistency of sticky red hair oil and at only one temperature: glacial. You had to break the ice some winter afternoons when taking a knee-bath after playing compulsory football or rugby. There may have been no village in the Carpathians quite as primitive as our part of London in the immediate run-up to the Swinging Sixties.

Even so, there was evidence that certain individuals might soon come to inject a splash of colour into the sepia tones that seemed to wash over the British landscape like a Victorian group photograph. By the spring of 1964 you could almost see their hopeful little heads poking out of the soil. There were the Beatles, to give just the most obvious example. The four impish Scousers had closed out the old year with a thirty-seven-date tour of Britain’s art deco fleapits from Carlisle to Portsmouth. At each stop a ruffle-shirted compère would bound on stage and demand, ‘Do you want to see John?’ (Roars). ‘Paul?’ (Roars). ‘George?’ (Roars). ‘Ringo?’ (Mayhem). A frantic pop party then ensued, with stretcher cases and arrests. As the curtain fell each night there was generally a full-scale riot in progress, suddenly ended, as if by a thrown switch, by everyone freezing in place for the national anthem. Early in the new year, the band went off to play in Paris and Paul McCartney had them send up a grand piano to his hotel room, the better to work on some of the songs that became A Hard Day’s Night. That the quartet were each reportedly making £100 a week (£1,500 today) didn’t slow them down: just the reverse. Later that winter McCartney turned up for a brainstorming session at John Lennon’s suburban home, as it happened not too far from ours, with the words, ‘Let’s write ourselves a swimming pool.’ Meanwhile, George Harrison was worried about keeping up payments on his new car, and Ringo just wanted to make enough to open his own hair salon. All four Beatles thought the band was a gas, but that it would be forgotten again in a year or two.

Harold Macmillan had resigned as Britain’s prime minister in October 1963, ostensibly on health grounds but really a victim of that year’s Profumo scandal, with its cast of characters including the eponymous Secretary of State for War, a society osteopath and sexual procurer named Stephen Ward, the assistant Soviet naval attaché, a pair of exotic, spliff-smoking West Indians, and two equally free-spirited young women of, as the parlance of the day had it, doubtful reputation. The press wasn’t slow to build the affair into a cause célèbre that linked not only senior members of the Macmillan Cabinet but Britain’s ruling elite as a whole to an underworld of prostitutes, pimps, spies, topless go-go dancers and unusual household practices. ‘The whole United Kingdom government has become a sort of brothel,’ The Times was left to sigh. I remember my father reading his evening paper around this time, grunting when he came to a certain passage, and remarking in a hushed tone to my mother that the news was all about ‘s-e-x’ those days. At that my mother had glanced hastily in my direction and put a finger to her lips. I respected the effort, but as it happened I’d recently learned the word for myself. I discovered it at school, where another boy had gravely informed me that ‘all the grown-ups – including the people in the Cabinet’ were at it like rabbits, a statement he illustrated by producing a pack of playing cards adorned by photographs of well-upholstered young women. The concept was reinforced via my passing acquaintance with a neighbour by the name of Lulu, whom I sometimes saw waiting for a bus at the end of our street wearing a dress of singularly sparing cut.

For a while in the summer of 1963, the Macmillan government tottered, seemingly fatally wounded. Although it survived, it lost its former aura of respectability. Deference was never quite the same again. Macmillan’s successor in office was the 60-year-old 14th Earl of Home (or plain Sir Alec Douglas-Home, as he became), a man whose misfortune it was in the television age to resemble a prematurely hatched bird and whose Adam’s apple danced rapidly up and down his narrow neck. His selection was not noticeably a step in the direction of modernising Britain. It was thought the wily, 47-year-old Labour leader Harold Wilson, ostentatiously puffing his pipe in public while enjoying a good cigar in private, understood the medium rather better. TV was ‘open to abuse by any charlatan capable of manipulating it properly, and so it proved in 1964,’ Wilson’s future opponent Edward Heath noted.

Both major political parties continued to struggle with the fallout of the tragicomic Suez affair of November 1956, when the British forces were comprehensively reverse-ferreted from their attempt to seize control of the canal zone amidst a disastrous run on sterling and the unexpected opposition of the Americans, and had since committed to phasing out their bases, harbours and other imperial-era establishments throughout the Middle East. Both also grappled with their stance on what was then called the European Common Market, the French having just vetoed Britain’s latest application to join the club. To a certain generation of Britons, it must seem as if their whole lives have been spent in the shadow of a stale and still not wholly resolved debate about their nation’s proper place on the Continent. As a whole, Macmillan’s premiership from 1957–63 falls broadly into a first half, where he appeared to be in charge of events, and a second half, which was increasingly devoted to dealing with domestic and foreign disasters. Coming to power at a time when respect for one’s ‘betters’ still predominated in all walks of life, and leaving it amidst a satirical firestorm that lampooned the PM as a broken-down figure presiding over an inept and sexually incontinent regime, Macmillan’s seven-year tenure was the trigger point for Britain’s 1960s modernisation crisis.

Aside from the accelerating plague of rock and roll, British parents were confronted by certain other unmistakable signs that the rallying legacy represented by the Dunkirk Spirit and the illusion of continuing post-war unity was starting to crack. Films as diverse as Dr Strangelove, Girl With Green Eyes, The Chalk Garden, King & Country, Of Human Bondage, The Pumpkin Eater and Zulu all appeared on British screens in 1964, each offering at least a hint of social commentary or satire about class distinctions. Joe Orton’s first play Entertaining Mr Sloane was an immediate succès de scandale when performed at London’s Arts Theatre that May. The opening act, in which a dowdy, middle-aged woman picks up a young, good-looking psychopath and informs him how positively she would react to any romantic overtures he might care to make to her gave notice that this was something other than traditional, all-round family entertainment. Top of the Pops, Match of the Day and Crossroads all made their debut on British television that year. The Rolling Stones released their first album in April, another key moment in blasting the parochial shackles off British pop music, perhaps even more so than the Beatles. Around the Stones in...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.2.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte |

| Schlagworte | 1960s • 1964 • 60s • BBC 2 • BBC Two • British cultural history • British social history • harold wilson • Match Of The Day • Motd • nelson mandela imprisonement • ninety sixty four • Rolling Stones • Sixties • Sixties culture • sixties history • The Beatles • the Pill • The Sun newspaper • Top of the Pops • TOTP • Vietnam War • White Heat • white heat of technology |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-601-3 / 1803996013 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-601-1 / 9781803996011 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich