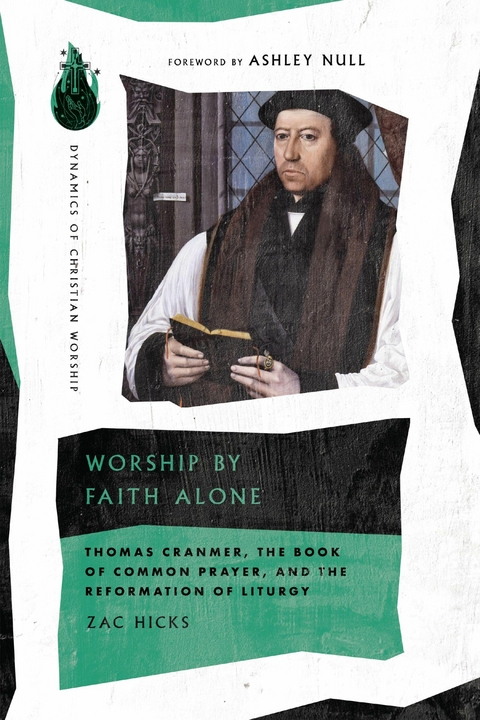

Worship by Faith Alone (eBook)

248 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0523-1 (ISBN)

Zac Hicks (DMin, Knox Theological Seminary) is adjunct lecturer in music and worship at Samford University, and author of The Worship Pastor: A Call to Ministry for Worship Leaders and Teams. Previously, he served as the Canon for Worship and Liturgy at Advent Cathedral. He lives with his wife, Abby, and their four children in Birmingham, Alabama.

Zac Hicks (DMin, Knox Theological Seminary) is adjunct lecturer in music and worship at Samford University, and author of The Worship Pastor: A Call to Ministry for Worship Leaders and Teams. Previously, he served as the Canon for Worship and Liturgy at Advent Cathedral. He lives with his wife, Abby, and their four children in Birmingham, Alabama.

Christianity has embedded in it the germ of antireligion that fights its own tendency to become a religion that is based in works-righteousness.

PROTESTANTISM AND GOSPEL-CENTRALITY

We have apparently arrived at a moment in Western evangelicalism where gospel-centrality is a thing. In the grand scheme of worldwide Christianity, it might not be a very popular or widespread thing, but it is a thing. Gospel-centered, gospel-shaped, gospel-driven, and the like have all but become brands in certain tribes and subcultures.1 Responding cries have challenged that all this talk has diluted the clarity of what the gospel is and what the gospel does. The longer I live and move and have my being in the realm of gospel-centered worship,2 the more I am sympathetic to these cries for clarity.

In the first chapter of his epistle to the Romans, Paul headlines his letter by describing the gospel as the “power” of God (1:16). The apostle then goes on to unpack that power over the next ten chapters. At the center of that enterprise is a stark antithesis: no one can be justified by works of the law, but instead justification is a gift, received by faith (3:20-25). This antithesis appears in Paul’s letters again and again as the way the gospel is made clear (e.g., 1 Cor 15:9-10; Gal 2:16; Eph 2:8-9; Phil 3:9). In other words, the gospel is proclaimed in all its power precisely when it is recognized and received by faith, apart from works. Paul speaks elsewhere of paradoxical instances where that power is absent even while its fruit is still apparent, albeit in counterfeit form. In his words, such people are caught “having the appearance of godliness, but denying its power” (2 Tim 3:5).3 I have begun to wonder whether the landscape of Western worship is not dotted, if not significantly fortressed, with expressions and practices which have the appearance of godliness—of worshipfulness, of piety, of passion, of zeal, of truthfulness, of even the right words and the right “biblical elements”—and yet deny the power that animates them all. I long for the kind of zealous, fiery worship marked by a “demonstration of the Spirit and of power,” and I believe, with Paul, that this demonstration happens best when worship has “decided to know nothing . . . but Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor 2:1-5).

This book seeks to clarify the Scripture’s vision for gospel-centered worship with the hope that such clarification might lead us toward a daring confidence that the very power that stands at the center of Christianity—the good news of Jesus Christ for sinners—is sufficient to withstand all contenders and lead the church into the uncharted waters of the future. But instead of directly surveying the Scriptures or overtly developing a liturgical theology of gospel-centrality, we might do well to come at this from the side.

Those of us who stand in the Reformation tradition of evangelicalism (before it was tarnished by cultural and political overtones, an evangelical was simply a “gospel-person”) have to admit that our commitment to sola scriptura is prone to being bastardized into a kind of strict biblicism which in turn closes our ears to other faithful Christians of the past who have read and interpreted the same Bible we prize. In other words, something in our Protestant DNA causes us to almost instinctively bristle at listening to the Great Tradition.4 Tradition, to say the least, is complicated, but in the best of light it is merely that repository of previous generations of Christians wrestling with what the Word of God was saying to them and then living out the work of that Word in their given time and place. If those of us in Protestant traditions would lift our heads for a second, we might be able to look back and notice that the question of what the Bible has to say about gospel-centered worship is not a new one. This was, in fact, my own far-too-late discovery. There I had been on my own for over a decade as a pastor and worship leader grappling with the Scriptures about what it meant for the gospel to govern and guide the worship service. Then one day, someone lifted my head, and I encountered a Christian who five hundred years ago asked those very same questions I was asking and answered them with far more knowledge, far more depth, far more work, and far more clarity. I had met the reformer, Thomas Cranmer.

If people are aware of Thomas Cranmer, they are likely acquainted with the fruit of his labor—the Book of Common Prayer, and the broad and global legacy of English-speaking worship that traces its history back to it. However, far fewer are aware of the labor itself. The goal of this book is to expose that labor in order to learn. This effort is nothing more than an attempt to transport ourselves five centuries back and stand over the shoulder of England’s greatest reformer as he sits bent over his candlelit desk, surrounded by hundreds of books, manuscripts, notes, and liturgies contemporaneous and historic.5 We will observe the Archbishop at work with these liturgical sources.6 When we do so we will see he is not only translating, but transposing. We will see him making decisions. And we will try to ask, on what basis is he making those decisions? Can we observe an undergirding set of criteria or a rationale behind what he chooses to keep, what he chooses to omit, what he chooses to move, and what he chooses to remain in place?

This book makes the claim that Cranmer indeed had such a rationale and that this rationale, though not exclusive and singular, so overwhelmed the Archbishop in its importance7 that it dominated all other criteriological motivations for liturgical redaction. Getting right to it, what overwhelmed Cranmer was God’s love for him in Christ, and once that love seized him, the Archbishop became fiercely committed to the clear proclamation of that good news.8 In other words, Cranmer’s vision for liturgical renewal was intensely fixated on the gospel. His evangelical convictions drove his liturgical decisions.9 If this is true, then I would suggest that as we look over the Archbishop’s shoulder, we will discover that he provides, among all sixteenth-century Reformers English and Continental,10 a most exemplary model of what it might mean to be gospel-centered in our worship today.

I want to be careful to recognize that gospel-centered is modern speak, and it is therefore terminologically anachronistic to refer to Thomas Cranmer’s gospel-centered theology. Still, the argument of this book is that it is not theologically anachronistic to view Cranmer’s work as an attempt at gospel-centered worship. In fact, I’m hoping Cranmer will provide for us a much more theologically rich and biblically faithful definition for what it looks like for worship services to be centered on Christ’s gospel. Nevertheless, I will attempt to use the phrase sparingly with reference to Cranmer’s work.

I further recognize the boldness of the claim that Cranmer’s evangelical convictions drove his liturgical decisions. Indeed, much ink has been spilled, including Cranmer’s own, about what his motivations were behind the choices made in the formation of the Book of Common Prayer. It will be helpful to briefly recount what has been said about Cranmer’s criteria for liturgical redaction, both to affirm their truth and to expose why they fall short of accounting for his great doxological obsession.

CRANMER’S CRITERIA FOR REDACTION

The Archbishop’s preface to the 1549 Book of Common Prayer states his methodological intentions plain enough, and we want to observe these stated reasons alongside some unstated ones that centuries of liturgical analysis make equally clear. Our goal here is to better understand Cranmer’s criteria for liturgical redaction and to set the stage for the argument that they inadequately account for all his liturgical moves. Cranmer’s criteria in eight broad categories are catechesis, affective persuasion, missional intelligibility, participation, unification, simplification, antiquity, and scripturality.

1. Catechesis. In Cranmer’s mind, the Scriptures themselves are the bedrock of the liturgy. Therefore, Scripture reading would be front and center in liturgical reform. Cranmer advocates this reform precisely so that believers and ministers can “be more able . . . to exhort other[s] by wholesome doctrine, and to confute them that were adversaries to the truth.”11 In short, one of Cranmer’s aims with the liturgy was to catechize the people. In the sixteenth century the average believer possessed limited biblical knowledge.12 The liturgy would serve as a primary place where this widespread biblical vacuum could be filled. And even though we will classify simplification as a separate criterion, we acknowledge with Bryan Spinks that simplification and catechesis for Cranmer went hand in hand: “In terms of his main Latin source, the Sarum rite, he simplifies for the purpose of education.”13

2. Affective persuasion. As a descendant of medieval affective piety, as a humanist in the school of Erasmus, and as a Protestant persuaded by Melanchthon’s Lutheran interpretation of Augustine’s affective theology,14 Cranmer was committed to the idea that a good liturgy did more than provide a framework for worship. The liturgy’s aim was to cause the worshiper’s heart to, in his words, “be the more inflamed with the love of [God’s] true...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.2.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Dynamics of Christian Worship | Dynamics of Christian Worship |

| Vorwort | Ashley Null |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Schlagworte | anglican • archbishop • Christian liturgy • Church of England • Church Service • DCW • Ecclesiology • ministry • music • Pastor • Thomas Cranmer • worship arts • worship leader |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0523-9 / 1514005239 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0523-1 / 9781514005231 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich