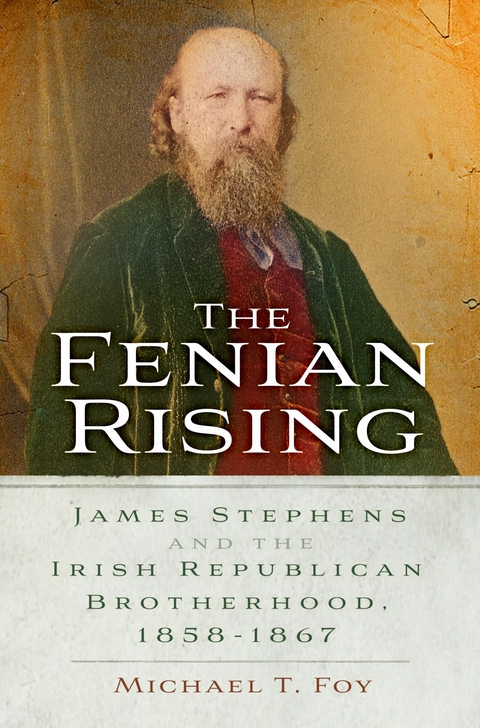

The Fenian Rising (eBook)

330 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-263-1 (ISBN)

Michael T. Foy is a former Head of History at Methodist College, Belfast and Tutor in Irish History at Queen's University, Belfast. He possesses an MA and PHD from Queen's University, Belfast. He has appeared frequently on Irish TV speaking on Irish history, and is the author of three previous books for The History Press. He lives in Co. Antrim.

2

Fenianism in the Doldrums

Soon after O’Mahony left Ireland in May 1861, Stephens and Luby spent several weeks traversing Cork, Kerry and Clare on their most successful tour yet, meeting IRB centres, establishing new circles and recruiting members. Simultaneously, IRB organisers founded circles in England, Scotland and Wales. Stephens also mended relations with the Phoenix defendants, whom he took on a yacht cruise across Bantry Bay. Relaxed and smoking his pipe, Stephens predicted that Queen Victoria would be the last English monarch of Ireland, impressing O’Donovan Rossa with ‘the strong faith he had in the success of his own movement. The way he always spoke to his men seemed to give them confidence. That was one of his strong points as an organiser.’1 For his part, Stephens recognised that Rossa was bold, courageous and imbued with an unbreakable will; finally, he realised that even a provisional dictator needed a talented inner circle – men like Rossa, Edward Duffy, Charles Kickham and John Devoy.

Twenty-one-year-old Duffy hailed from Co. Mayo. After his father died, Duffy left school prematurely and worked as an apprentice at a dry goods business in Castlebar before moving to Dublin, where he joined the IRB. Dynamic and gregarious, Duffy swiftly became known as the Fenian Emmet, though even his great friend John O’Leary regarded this praise as excessive.2

Thirty-three-year-old Kickham was from Tipperary, the son of a drapery shop owner.3 Aged 13 he had suffered catastrophic injuries after a gunpowder flask accidentally exploded, leaving him almost blind and deaf as well as facially disfigured. Unable to work, Charles overcame his visual impairment to read the classics and publish poetry, while he also gravitated politically to militant nationalism. Kickham impressed Stephens, who tried recruiting him for the IRB, but he preferred open defiance of British rule to a conspiracy. Three years later, Charles changed his mind after meeting O’Mahony during the latter’s Irish mission. Converted to Fenianism, he joined the IRB in March 1861.

Nineteen-year-old John Devoy came from a small townland in Co. Kildare, where his father William farmed a tiny patch of land.4 In 1849 the family relocated to Dublin, where William eventually became managing clerk at Watkin’s Brewery. At school, John’s rebelliousness landed him in perpetual trouble. He refused to sing ‘God Save the Queen’, kicked a teacher who tried to cane him, and punched another sadistic teacher who wrung his ears. Upon leaving school, Devoy attended night classes in Irish that covertly propagated militant nationalism, and in early 1861 he joined the IRB. Totally inexperienced in warfare, Devoy decided to join the French army, and he even rebuffed Stephens’s advice to fight instead in an imminent American Civil War. Stephens remarked: ‘That young man is very stubborn.’ But in Paris, a virtually penniless Devoy discovered that foreign citizens could not join the French Army, and enlisted in the Foreign Legion instead. Devoy served briefly in Algeria before returning to the family home in Dublin. Stephens realised he had matured and appointed him IRB organiser at Naas in Kildare.

By now, Stephens and the IRB were suffering from a lack of money, especially Irish-American funding. Between April 1861 and April 1862, the Fenian Brotherhood sent Stephens just £113, a sum that he told O’Mahony was pitiable. Stephens also claimed falsely that he was actually raising more in Ireland, when in fact the IRB was almost completely dependent on America. By mid-1862, Stephens himself would be almost penniless, forced to borrow 10s for food from Luby – who himself was loaned the money.5 But, as always, Stephens saw everything through the prism of his own needs, even when civil war in America threatened the Fenian Brotherhood’s very existence. Whole circles vanished, the majority that survived were skeletons, and the most active members had left to fight. Between 150,000 and 170,000 men of Irish descent joined the Union Army, and 40,000 fought for the Confederacy, six of whom became Southern generals. Philip Sheridan, the son of Irish migrants from Cavan, established an Irish Brigade and became a Union major general. Another Union major general, Michael Corcoran, just managed to dissuade O’Mahony from enlisting by insisting this would leave the Fenian Brotherhood rudderless.

Despite his strong support for the Union cause, the war’s seemingly endless slaughter depressed O’Mahony, who declared that the sheer scale of Irish-American casualties had left thousands ‘whitening Virginia with their bones. This is a real blood-market.’6 Perhaps 35,000 died between 1861 and 1865. The Battle of Antietam in September 1862 decimated the Irish Brigade, which suffered 600 fatalities. Three months later, when General Robert E. Lee crushed the Union Army at Fredericksburg in the war’s most one-sided battle, the Brigade lost another 545 soldiers. This carnage reached its apogee in July 1863 at the three-day Battle of Gettysburg, a bloodbath that virtually wiped out what remained of the Brigade, which lost 320 out of its remaining 530 men. Civil war shredded the Fenian Brotherhood. Fifty branches folded as O’Mahony struggled virtually single-handedly to keep the movement alive. This disarray caused a scarcity of money for the IRB, but more importantly as long as civil war lasted, it made an Irish rising impossible because an American naval expedition to Ireland was out of the question.

As American funding dwindled to a trickle, IRB expansion in Ireland stalled, leaving it just one – and not the most important – political organisation vying for the leadership of nationalist Ireland. Most prominent were Young Irelanders like William Smith O’Brien, John Blake Dillon and John Martin, who had returned from exile in the mid-1850s and reconciled themselves to constitutionalism. However, although widely respected, these three grandees had retired from direct political involvement and exercised influence through public pronouncements and private advice. Instead, after 1855, George Henry Moore, MP for Co. Mayo, commanded the Tenant League’s shattered ranks, assisted by A.M. Sullivan, proprietor of Ireland’s biggest-selling daily newspaper, The Nation. But, after the general election, Moore was expelled from parliament for electoral intimidation. His successor, the Tipperary M.P. Daniel O’Donoghue, known universally as The O’Donoghue, was a superb orator and widely regarded as the most popular man in Ireland.

By 1860–61, popular interest in Irish politics was reviving. Frustrated at his stalled career, George Moore resurfaced and proposed an Irish Volunteer force that would compel the British government to concede legislative independence. However, Dillon told Moore that without an Anglo–French war he should either accept British rule and assimilate, or migrate to a more hospitable country. Crushed, Moore abandoned his project. Instead, on 5 May 1861, A.M. Sullivan launched a national petition for an Irish plebiscite on legislative independence. Despite knowing that the British government would not grant an Irish parliament, he hoped that huge support for his campaign would demonstrate the national will. And indeed, almost every social class endorsed the petition, which eventually attracted almost half a million signatures.

Well before the petition was presented to parliament in June 1861 and inevitably rejected, Sullivan had tried to capitalise on its mass mobilisation by proposing a new national political organisation. However, he was pre-empted by Thomas Neilson Underwood, a 31-year-old barrister from Tyrone, who had abandoned his London legal practice for a political career in Dublin. Announcing a banquet at the Rotunda on 17 March 1861, Underwood only gave Sullivan the minor role of replying to the toast. Many prominent constitutional nationalists attended the banquet, including The O’Donoghue, and most of the audience were moderate nationalists sick of parliamentary politics but opposed to physical force. However, on a pedestal on the podium sat the figure of a large phoenix bird with extended wings rising above the ashes. And a cohort of spectators repeatedly hissed mentions of William Smith O’Brien. Underwood proposed a new patriotic organisation called the National Brotherhood of St Patrick, whose nebulous principles included ‘the union of all Irishmen for the achievement of Ireland’s independence’. The sole qualification for membership was a belief that no foreign power could make laws for the Irish people. A show of hands endorsed Underwood’s proposal.7

Sullivan branded the NBSP a Fenian conspiracy, especially after IRB leaders like O’Donovan Rossa attended similar banquets in Belfast, Carrick-on-Suir and Cork. In fact, almost certainly Stephens had no prior knowledge of Underwood’s intentions, but it suited him very well that the NBSP showed Irish nationalism was stirring once again. Moreover, the IRB’s young Dublin militants immediately began infiltrating the NBSP, making it both a front organisation and a recruiting ground for Fenianism. Denieffe boasted that ‘as it was an open institution, we all became members and maintained a controlling influence’.8

However, in 1861 the new organisation was essentially a sideshow to a greater reality. By then sluggish recruitment, waning morale and a sense of drift had brought Fenianism in America and Ireland to such a low ebb that O’Mahony...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.12.2023 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 25 mono |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Systeme | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Theorie | |

| Schlagworte | 19th Century Ireland • british rule • Dublin Castle • history of Ireland • Home Rule • IRB • Ireland • Irish Nationalism • Irish Republican Brotherhood • James Stephens and the Irish Republican Brotherhood • Manchester martyrs • revolutionary Ireland • the fenian brotherhood |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-263-8 / 1803992638 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-263-1 / 9781803992631 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich