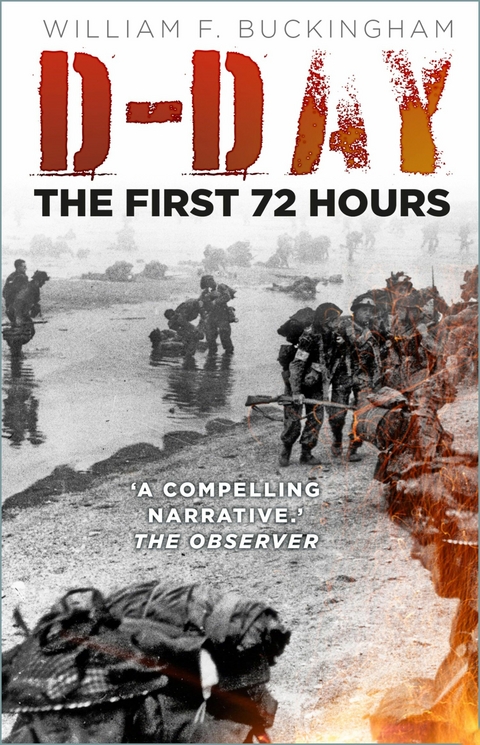

D-Day: The First 72 Hours (eBook)

330 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-9641-2 (ISBN)

WILLIAM F. BUCKINGHAM completed his PhD on the establishment and initial development of British Airborne Forces in 2001. His books include Arnhem 1944. He lives near Glasgow.

1

RHETORIC, RAIDERS AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE OVERLORD PLAN

JUNE 1940-JUNE 1944

At 04:30 hours on the morning of 10 May 1940, forty-two Luftwaffe Junkers 52 transport aircraft lifted off from airfields around Cologne, each towing a DFS 230 troop-carrying glider. Two machines were obliged to abort after take off due to tow-rope failure. An hour later, in the last minutes of pre-dawn darkness, the remaining gliders cast off just short of the Belgian-German border. As first light tinged the sky, they began landing on the meadow atop the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael, protecting three nearby bridges across the Albert Canal. The gliders carried assault pioneers from 7 Flieger Division, who moved to their objectives with the fluidity and speed generated by intensive practice. A mere ten minutes after touchdown, the fort’s observation cupolas and gun turrets had been destroyed or disabled with specially designed shaped charges and flame-throwers. Two of the three bridges were also seized, and a bridgehead established at the third after the defenders triggered their demolition charges.1

The attack on Eben Emael was the opening move in Operation Sichelschnitt (Cut of the Scythe), which involved three German Army Groups fielding a total of ninety-three divisions. The Eben Emael operation heralded a feint attack into the Low Countries while the main focus of the German attack was an armoured thrust through the Ardennes region, which forced the River Meuse at Dinant and Sedan on 13 and 14 May 1940. Allied counter-attacks failed to stem the German advance, and the Panzers reached the Channel coast south of Boulogne on 21 May, trapping the bulk of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the Pas de Calais. An ad hoc evacuation, codenamed DYNAMO, was launched on 27 May. Over the next week 311,586 British, French and other Allied personnel were lifted from Calais, Dunkirk and adjacent beaches.2 The rest of the BEF was evacuated from ports along the north and western French coast by 20 June 1940.3 The price of the evacuation was high. The BEF lost 68,111 of its personnel in France killed, missing or as POWs, and mere fractions of its stores and heavy equipment were salvaged. In all, 2,472 guns, 63,877 vehicles, 105,797 tons of ammunition, 415,940 tons of assorted stores and 164,929 tons of fuel were left behind.4

This then was the sequence of events that made a cross-Channel invasion necessary almost exactly four years to the day after the end of Operation DYNAMO. In the more immediate term, it also provided the catalyst for a number of practical measures without which the Normandy invasion in June 1944 would have been far more difficult, or even impossible. The main driver behind this was Winston Churchill. Made Prime Minister on the same day the German offensive began, Churchill actually began issuing directives aimed at returning to the offensive before Operation DYNAMO had run its course. On 3 June 1940, in a minute to the Military Secretary to the Cabinet, General Sir Hastings Ismay, warning against the dangers of adopting a defensive mindset, Churchill also mooted raising a 10,000-strong raiding force.5 He expanded on the latter topic two days later in a further minute that ended with a number of specific proposals. These included a call for suggestions for delivering tanks onto enemy-held beaches, setting up intelligence gathering networks along German held coasts, and the establishment of a 5,000-strong parachute force.6

The War Office and Air Ministry response was commendably swift in the circumstances. On 6 June 1940 the War Office authorised raising a raiding force, dubbed Commandos in honour of the Boer guerrillas of the same name,7 and three days later the Army’s Director of Recruiting and Organisation (DRO) called for volunteers for unspecified special service.8 On 10 June the Air Ministry formulated its response to Churchill’s demand for a parachute force, and the Army Chiefs of Staff included additional parameters for prospective parachute volunteers into Commando recruiting instructions.9 Two days later Lieutenant-General Sir Alan Bourne RM was appointed the first Director of Combined Operations;10 his higher ranking successor, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes supplanted him on Churchill’s instructions on 17 July.11 Bureaucratic measures were accompanied by the practical. By July 1940 twelve 500-strong Commandos were forming, and the new joint-service Parachute Training Centre at RAF Ringway had been established. Combined Operations carried out its first live operation on the night of 24-25 June 1940; Operation COLLAR saw five small parties landed at three separate spots south of Boulogne. A second raid, codenamed AMBASSADOR, was aimed at the airfield and installations on recently occupied Guernsey on the night of 15-16 July 1940.12

This was commendable but by no means flawless progress. The Commando idea was not universally accepted, and there were difficulties in obtaining volunteers, obliging a second recruiting drive in October 1940.13 Even then, the War Office department tasked to implement the Commando directive had to invoke the CIGS to force recalcitrant Commandos to comply with its instructions.14 The peculiar Commando conditions of service were also problematic. Such postings were temporary,15 and units were soon agitating for the return of their volunteers,16 and morale suffered when the separation between volunteer and parent unit caused problems with pay and allowances for dependants. In addition, Commando volunteers were not provided with billets or rations, but were expected to make their own arrangements with a monetary allowance, amounting to thirteen shillings and four pence per day for officers, and six shillings and eight pence for other ranks.17 This still brought the War Office into conflict with the Ministry of Food, particularly when Commando units moved into rural areas for training.18

These teething troubles do not detract from what was highly creditable progress, given the threat of seemingly imminent invasion and the need to rebuild the British Army. According to received wisdom, Churchill’s rationale in demanding the formation of Commando and Airborne forces was to carry out pin-prick raids to boost British civilian morale, which by happy accident later developed into one capable of spearheading more conventional operations as well. In the process this involved a largely needless and wasteful diversion of high quality manpower and other resources that would have been better employed elsewhere. This explanation is very popular with Churchill’s critics and those generally opposed to the creation of so-called ‘elite’ forces alike.19

It is easy to see how this view was formed. Arguably the biggest culprit was Churchill himself, because of the language in which he couched his directives. His initial minutes, for example, advocated developing a ‘reign of terror’ along German-held coastlines via a ’butcher and bolt’ policy. This language was mirrored in internal War Office communications, which invariably referred to the new Commando force as a basis for ‘irregular units’ and ‘special parties’ with no fixed organisation and intended for ‘tip and run tactics depending on speed, ingenuity [and] dispersion’.20 Churchill’s badgering for action without delay reinforced this interpretation, if only because the lack of time and resources made small-scale raiding the only immediate option.

This interpretation also fitted neatly with a pre-existing War Office interest in irregular warfare. This went back at least to the end of the First World War, with British involvement in such operations in Russia and Ireland. A small section entitled General Staff (Research) was set up in the mid-1930s, being expanded and renamed Military Intelligence (Research) in early 1939. As well as publishing pamphlets on guerrilla operations, MI(R) carried out covert intelligence gathering in Rumania, Poland and the Baltic States, and was involved in an abortive scheme to assist the Finns in the Winter War.21 In April 1940 ten ’Independent Companies’ were formed for irregular operations in Scandinavia, five of which briefly saw action.22 Administrative convenience may also have played a part in focusing Churchill’s directives into raiding. This appears to be the only reason the War Office folded the parachute requirement into the Commando recruiting effort,23 for example, and the Air Ministry used the same excuse for its unilateral reduction of the parachute requirement from 5,000 to 500.24

However, there is evidence to counter the raiding interpretation of Churchill’s directives, starting with what Churchill actually asked for. The first minutes called for the raising of not less than 10,000 raiders, with an additional and separate requirement for 5,000 parachute troops. This clearly shows that Churchill did not consider the two requirements indivisible, and a total force of 15,000 men was a considerable force for small-scale raiding under any conditions. This in turn strongly suggests Churchill had a more substantial purpose in mind, and he was not alone. In July 1940 Major John Rock RE, ranking Army officer at the Parachute Training Centre, requested the War Office reserve the new parachute force for key tasks like the ‘...capture of a Channel port for an invasion of France’.25 In fact, planning for an airborne brigade group was already underway, leading to a formal requirement for two all-arms ‘Aerodrome Capture Groups’.26 Such thinking was not restricted to the embryonic airborne force either....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.5.2004 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | airborne invasion • Allied Invasion • amphibious invasion • battle analysis • d-day:d day • France • hour by hour • naval invasion • Normandy • oepration overlord • Second World War • UK • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-9641-7 / 0752496417 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-9641-2 / 9780752496412 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich