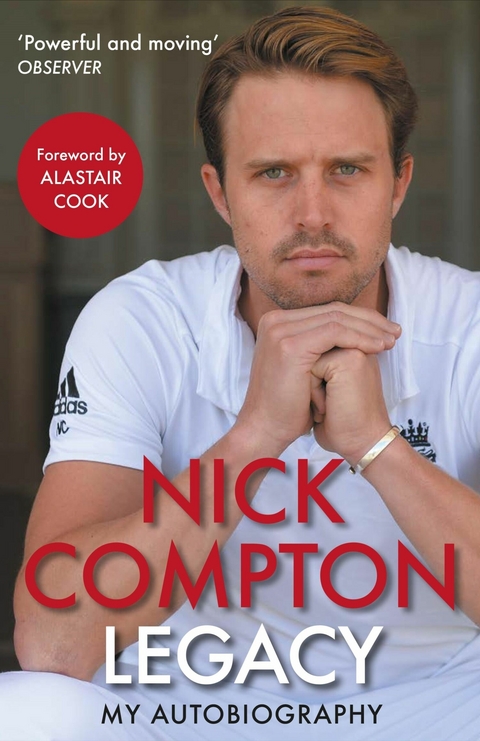

Legacy - My Autobiography (eBook)

320 Seiten

Allen & Unwin (Verlag)

978-1-83895-826-8 (ISBN)

Nick Compton is a South African-born English former Test and first-class cricketer who most recently played for Middlesex County Cricket Club. The grandson of Denis Compton, he represented England in 16 Test matches, scoring two centuries. A right-handed top order batsman and occasional right-arm off spin bowler, Compton established himself as a consistent scorer in county cricket for Middlesex and Somerset, and, following a prolific domestic season, he made his England Test debut against India in November 2012. In April 2013, the Wisden Cricketers' Almanack named Compton as one of their five Wisden Cricketers of the Year. Compton retired in 2018 and is now a professional photographer and broadcaster.

Nick Compton is a South African-born English former Test and first-class cricketer who most recently played for Middlesex County Cricket Club. The grandson of Denis Compton, he represented England in 16 Test matches, scoring two centuries. A right-handed top order batsman and occasional right-arm off spin bowler, Compton established himself as a consistent scorer in county cricket for Middlesex and Somerset, and, following a prolific domestic season, he made his England Test debut against India in November 2012. In April 2013, the Wisden Cricketers' Almanack named Compton as one of their five Wisden Cricketers of the Year. Compton retired in 2018 and is now a professional photographer and broadcaster.

Chapter 2

Grandad

My grandfather was not only regarded as one of the best batsmen of his generation, but among the greatest cricketers ever to play the game. Denis Charles Scott Compton, youngest son of a painter and decorator from North London, was an entertainer, wielding a rapier made of willow who made England cheer again in the dark post-war days of austerity. He brought instinct, flair and vibrancy to the game, standing up to the ‘Invincibles’ Australian side led by Don Bradman in 1948 and hitting the winning runs when England finally reclaimed the Ashes in 1953 in front of a baying crowd at The Oval.

His iconic stature was probably best captured by the great writer Neville Cardus who wrote of his phenomenal performances in the summer of 1947 when he scored 3,816 runs at an average of 90, including 18 centuries:

‘Never have I been so deeply touched on a cricket ground as in this heavenly summer, when I went to Lord’s to see a pale-faced crowd, existing on rations, the rocket-bomb still in the ears of most, and see the strain of anxiety and affliction passed from all hearts and shoulders at the sight of Compton in full sail, sending the ball here, there and everywhere, each stroke a flick of delight, a propulsion of happy, sane, healthy life. There were no rations in an innings by Compton.’

But to a young boy growing up five decades later in faraway South Africa, he was just Grandad who once played Test cricket for England and football for England and Arsenal (with whom he won the League Cup and the FA Cup) and advertised a mysterious hair gel called Brylcreem. I was proud, obviously, and had posters and photographs of him on my bedroom walls, caressing the cricket ball through square leg or dressed like James Bond in black tie while signing autographs for wide-eyed girls.

But I was too young at that stage to really understand what he had achieved. On the few occasions that I was in his company it would not have occurred to me to ask him what it was like facing Ray Lindwall or Keith Miller, the Australian quick bowlers of his day. I was more interested in my own, present-day heroes; I wanted to be one of the South African stars, Jacques Kallis or Jonty Rhodes or Andrew Hudson.

I didn’t see much of Grandad when I was a kid, other than a handful of trips he made to South Africa or the few occasions that we came to London. He was an unseen presence in our lives, the reason that people in the street and the sporting clubs of Durban knew our names, although not one to mention in front of his ex-wife, my late, rather regal grandmother, Valerie.

The first visit I recall was when I was about eight years old and a tearaway striker for the local football club. It was the first sport in which I had showed real promise, selected in underage Natal teams. I was quick and incredibly competitive, even at that age, and out to impress my famous relative. If I close my eyes and concentrate, I can still smell the orange wedges the coach was handing out at half-time that day in a small suburban park while Grandad sat watching from a rickety grandstand by the side of the pitch.

I scored a hat-trick and one goal, in particular, was spectacular. I was playing on the left-hand side of the pitch where I got the ball and dribbled down the touchline before switching inside, around an opponent to the edge of the box and hitting it into the top right-hand corner of the net, just like he used to do when he played for Arsenal. My father remembers Grandad leaping in the air despite his gammy knees and yelling ‘That’s my boy’ as I scored.

Grandad came back to Durban a couple of years later and visited my prep school. It was at this moment that I had an inkling of just how famous he was when the headmaster and teachers rolled out the red carpet for him. Everyone was in awe of Denis Compton, and I could now picture what it was like to be a champion.

I was twelve years old when he first saw me play cricket, not in Durban but in England. I had come on a school tour, accompanied by Dad, and stayed with him at his home in Burnham Beeches, in Buckinghamshire. He came to watch me in a match played at the nearby Caldicott School where I think I got 45 out of the team’s total of 120.

Dad told me that Grandad had turned to him and said something like: ‘You know, he’s got some fight in him, this kid.’ Those sorts of comments really meant something to an impressionable child, not just in the moment but as my career went through its ups and downs. Whatever anyone else observed of me out there in the middle, fight was the word that came to define my own view of myself.

Dad and I stayed on with Grandad for a week after that tour, during which time there was another significant moment for me. I was in his back garden one day, practising diligently as Dad patiently threw balls. Grandad was watching, sitting at a table on the veranda sipping brandy, as was his wont. I was trying to show him how straight my bat was, blocking the ball carefully back to Dad, but after watching for a while, Grandad blurted out: ‘Oh, for heaven’s sake, just hit the bloody thing.’

I never forgot that, not just because of the way he shouted it in frustration but because, like the word ‘fight’, it became very pertinent to my career. In my worst times, when my confidence was low, I had a tendency to overthink things and become too technical. There were times when I got stuck like that out in the middle and I’d just remember his words and think, Oh for fuck’s sake, stand still and just hit the damn thing. It made the game simple.

As much as we were compared during my playing career, the truth was that Grandad and I were cut from very different cricketing cloth. I mean, I was into fitness and health drinks and he had the fortitude of an ox, getting to the ground after a night partying and then going out with a bat borrowed from a tail-ender and scoring a century. That was the mythology at least.

He had real charisma on and off the field, a man of the people long after he finished playing who, when not at Lord’s, could usually be found at a private members’ club, The Cricketers, off Baker Street where he was president and used to go for long lunches most afternoons, holding court with his lunch companions and other admirers in the restaurant who would gather to hear him tell stories. He had this manner where he would lower his voice, almost to a whisper, to ensure that people would crowd forward to hear what he had to say before launching into a rakish story about his friendship and adventures with his great mate, the Australian all-rounder Keith Miller with whom he had battled for the treasured Ashes.

The Brylcreem (an emulsion of water and mineral oil stabilised with beeswax) that defined his image as a player was long gone and his jet-black hair was now a lush silver, but he cut a broadening but well-dressed figure who could speak with a clipped accent despite his working-class background.

He was also Middlesex president at the time and took me around Lord’s one day, past the stand that bears his name. Here I was, a twelve-year-old with eyes as big as dinner plates, walking around the palace of cricketing dreams. It cemented my desire to play there, particularly when he arranged for me to pad up and face Mark Ramprakash and Gus Fraser in the nets. I couldn’t have guessed then that Gus would be my captain five years later when I made my debut for Middlesex. It’s unfortunate that Grandad wasn’t around to see it. He died the year after that memorable underage tour, aged seventy-eight.

Was Grandad an influence on my life as a cricketer? Of course he was. Was he the reason that I wanted to play cricket? No, I had a bat in my hand from the age of three, although his achievements were certainly a driving force for me to succeed at the highest level. His legacy did not ensure my selection to play Test cricket but it cleared away some of the branches hanging across the pathway towards the top, especially in the early days when the name Compton meant something in a place like Natal.

But there was a flip side to this legacy. The shadow of expectation and comparison was constantly on my shoulder. I did not feel it so much as a youngster, but the higher I climbed in the game the more it bore down on me. For the most part I didn’t feel the pressure, especially when I was playing well, but I could sense in others the rush to compare, particularly in the media which either delighted in slicking back my hair with Brylcreem for photo shoots or, when I was down and struggling, drawing unflattering comparisons between my slow, methodical batting and his cavalier scoring. But I don’t remember ever thinking I’m not as good as Grandad. I just wanted to be the best player that Nick Compton could be.

Some of this analysis was, of course, valid. After all, cricket is a game of statistics, and I am the first to acknowledge that performance is everything in terms of team selection. But statistics can also be misleading – between matches and seasons, let alone generations – so they should always be made carefully with context.

Our challenges were different. It was much less about brawn and power back when he played. The bats were thinner and lighter and the pitches weren’t as good, so the sweep and the late cut were examples of the touch and the ability to manoeuvre the ball rather than just hit through the line. Batting techniques were more individual.

I was brought up on coaching manuals and bowling machines, heavier bats, true pitches and raw, fast...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.7.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Ballsport | |

| Schlagworte | andy flower • Ashes • australia cricket • Cricket • cricket biographies • Denis Compton • Depression • england county cricket • England Cricket • Jonny Bairstow • Kevin Pietersen • kevin pieterson • middlesex county cricket • nick compton • somerset county cricket • South Africa • Sport • sporting legends • Wisden |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-826-6 / 1838958266 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-826-8 / 9781838958268 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich