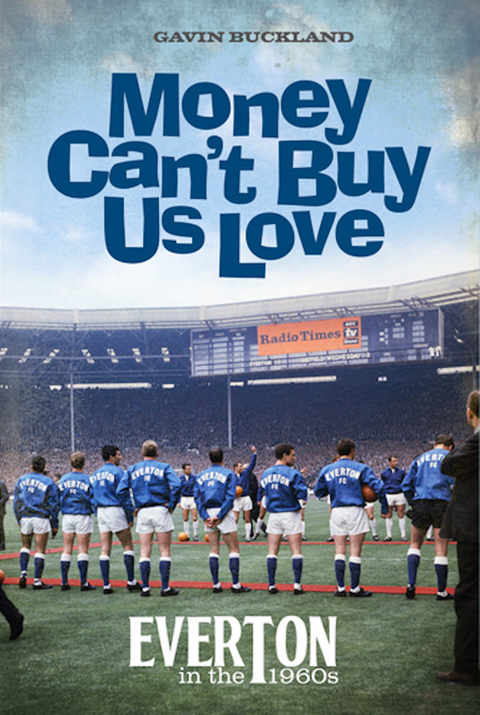

Money Can't Buy Us Love (eBook)

384 Seiten

deCoubertin Books (Verlag)

978-1-909245-59-4 (ISBN)

Gavin Buckland is official statistician to Everton FC and has written a number of books about the club, including Strange But Blue. He has checked the questions for BBC TV's A Question of Sport for more than 20 years, and has set questions for several football-related TV quiz series.

2.

‘The King is Dead, Long Live the King’

John Moores – the Manchester Messenger

Born in Eccles, Greater Manchester, in January 1896, John Moores was one of a family of eight children. Even from an early age the future Everton chairman showed the entrepreneurial skills that would make him one of the richest people in Britain. Encouraged by his mother, Moores moved quickly after his first job as a six-shilling a week messenger boy for the Post Office, where the self-confidence and single-mindedness that characterised his rise to the top ultimately lead to his departure. After Moores objected to instructions to work during his break, the head messenger warned him that ‘In future you’ll do as you’re told.’ Moores replied ‘I won’t,’ and left by the end of the week.

Moores’ next job was as a trainee telegraphist with the Commercial Cable Company, which in many ways shaped everything that came afterwards. Shortly after World War One ended, the role took Moores to Liverpool for the first time, for training in Bixteth Street. The visit began a love affair with the city and its people that was to last more than seventy years, but typically one that worked both ways; asked once why he had never moved south, Moores replied: ‘I have made money out of this area and I like the people here.’

With training complete Moores was then stationed to Waterville Cable Station in County Kerry, Ireland. Following complaints over food, Moores was elected Mess President – effectively granting him overall management responsibility for catering – where for the first time he displayed the leadership skills and business acumen that would define him. Moores picked the committee members himself and after discovering that suppliers were overcharging, formed the Waterville Supply Company to source their own food, reducing costs and improving the standard of cuisine. Other Moores-led initiatives included the purchasing of books for the station’s library and, with the local golf course having no club shop, agreeing a deal with Dunlop to become their agent for ‘the supply of golf requisites’ in the area. With these lucrative sidelines, at a time when the average wage was £3 per week, Moores was earning nearly ten times as much, thanks to his hard work and gift for identifying gaps in the market.

With his appetite for success and wealth whetted, Moores was continually looking for additional ways of generating money. One of his companions in Ireland was Colin Askham, a friend from his days as a messenger boy in Manchester. After 18 months in Ireland,1 both men returned to Liverpool and teamed up with another former messenger boy, Bill Hughes. Taking their lead from a football pool run in Birmingham, they devised their own venture, putting up £50 each as start-up costs. The company’s name of Littlewood originated from the adopted Askham’s actual surname at birth, his business partner having been orphaned at a young age.

The first 4,000 coupons were distributed before a Manchester United game at Old Trafford in February 1924. Famously only 35 coupons were returned, the three founders’ income after the dividend not even covering their costs. Midway through the 1924/25 season, after contributing £200 each with little return, the trio convened a crisis meeting. After his two partners suggested they cut their losses and close the business down, Moores surprisingly disagreed, and offered to pay back both their original investment in return for all their shares. ‘I still believe in the idea,’ he informed them.

The Mersey Millionaire

Moores’ hunch proved correct: within three years the company was turning over more than £200,000 annually and by 1932 he was a millionaire. By then Moores was expanding into mail order catalogues and chain stores on the way to creating the largest private company in Europe.

As well as running the business, Moores had always been a man with a wide number of outside interests, including golf and painting. Moores had also watched Everton from his early days in the city and was a spectator when Dixie Dean scored his record-breaking sixtieth league goal in 1928. After acquiring shares in both Everton and Liverpool, he began a family association with football in the city that still exists today. The Littlewoods chief later explained why it was Everton, and not their rivals, who put the connection on a more official footing. ‘I was asked to put money into Everton, which they were to repay,’ Moores said in 1964. ‘At first it was £36,000 for floodlights then came more money for players. They also began to ask my advice on business matters. Soon it was suggested that I join the board to see my money spent. That’s how I came to join the one club rather than the other.’

Two years earlier Moores had told Bob Ferrier of the Observer that there was another motive for getting involved. ‘I’ve always been an Everton man2 – can’t tell you why. For ten years I watched the club flounder in management. It got so bad I took to going to St Helens to watch Rugby League.’ Moores later told Ian Hargraves of the Liverpool Echo of an unexpected shock when he joined the board in March 1960, ‘I was surprised to find the club was actually in the red, and I was struck by the amount of waste and the money that was being lost by inefficient use of resources.’ For a man used to being in charge, being a board member was always going to be a temporary appointment.

The chairman, June 1960

Unsurprisingly, within three months Moores was appointed chairman, at the annual shareholders’ meeting in June 1960. The people who ran football clubs, before Moores arrived, had traditionally been the local businessman made good. That was about to change when the multi-millionaire joined the Everton board. Whether it was intentional or not, Moores gave the impression of wishing to run the club on the lines of the continental giants – Littlewoods underwriting expenditure in the same way that, say, the Agnelli family had used their Fiat fortune to support Juventus. This was taking English football into new territory, and it was a vision that Moores reiterated when he entered the boardroom. ‘We want the best players, the best coaches, the best trainers and the best directors, he proclaimed, ‘Whether I shall prove to be one of the best directors will be answered in time.’ Moores immediately brought his business expertise to bear, making the financial changes required to bring some stability – a loss of £49,504 in 1959/60 becoming a profit of £25,504 in 1960/61.3

With his corporate business background, Moores was very much a modernist who also remained frustrated at the archaic structures at the top of the English game, which hindered the progress of the big clubs, especially when compared to those overseas. The biggest source of his frustration was the ‘three-quarters’ majority rule in the Football League, derived from each club in the top two divisions having a single vote each, with the bottom two tiers having four votes collectively. Of the 48 votes available, 36 was the amount needed to instigate change, but this rarely happened as the smaller clubs grouped to scupper the plans of the elite.

‘If we want really big professional football as a spectacle, that is one thing,’ he told Bob Ferrier, ‘but it is very different from what we have at the moment.’ Moores also believed that the big teams should have the best players appearing in modern stadia. ‘As it is now, we are at the mercy of clubs who cannot compete with us, but can veto our progress,’ he said. ‘The three-quarters majority rule is crippling the future of the game, we cannot tolerate amateur minds sitting in judgement on us.’ Moores tried to bend his counterparts’ views to match his own by widely circulating his correspondence with the Football League to fellow chairmen – and usually succeeded.

In August 1960, Moores led the protests over the £150,000 ITV television deal with the Football League to show matches live on a Saturday evening, as their management committee did not consult with the clubs. The Everton chairman voiced his fears in writing to all those in the top two divisions, and the agreement was effectively scrapped in the opening months of the season. Six months later, when the proposed ‘new deal’ with players may have allowed them to walk out at the end of their contracts, Moores – fearing the loss of his expensively assembled assets – wrote to the Football League for an assurance that there was no right to a transfer when contracts ended, circulating the letter to all 92 league clubs. The move proved highly influential and at their extraordinary meeting in April 19614 the clubs voted to resist the change.

Moores reserved his biggest gripe for the insular view of the game in England. In business Moores had been a regular traveller to the United States, visiting their equivalent companies to Littlewoods, returning to England with new plans to drive the firm forward. On cruises Moores would sound out fellow businessmen from across the Atlantic in an exchange of ideas and opinions. Moores was keen to apply the same principles to running Everton, but the ruling bodies and clubs in this country were averse to allowing overseas influences, protected by the restrictive employment practices operating at the time – there had been a longstanding Ministry of Labour and FA rule that overseas players had to serve a two-year residency period in this country before becoming eligible to play in the Football League. Such blinkered thinking annoyed the visionary Moores, as the sight of Real Madrid winning five European Cups with a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.8.2019 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| ISBN-10 | 1-909245-59-3 / 1909245593 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-909245-59-4 / 9781909245594 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 15,9 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich