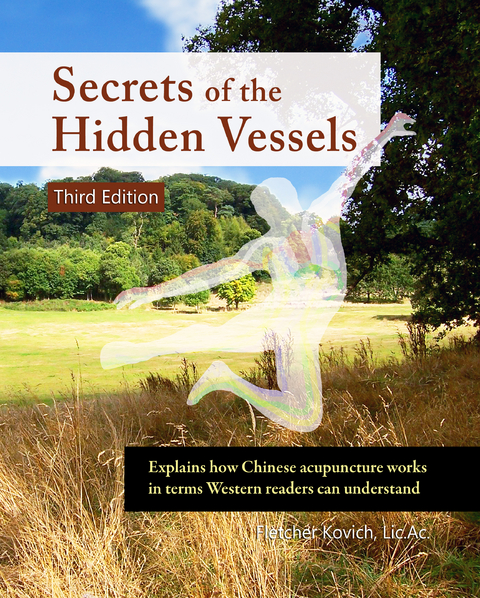

Secrets of the Hidden Vessels (eBook)

1693 Seiten

CuriousPages Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-9164830-5-7 (ISBN)

The Nei Jing consists of ancient Chinese scripts and is the foundation of Chinese acupuncture. But several factors make the Nei Jing, and also today's Chinese medicine, difficult to comprehend.

Parts of the Nei Jing are fact based, parts are metaphorical and not intended to be interpreted literally, and other parts contain contradictory theories, which cannot all be true. Added to this is the problem that Chinese medicine concepts can seem incomprehensible to Western readers anyway.

This book tackles these problems by relating Chinese medicine knowledge to today's physiology and identifying the overlap. The book also extensively analyses the Nei Jing theories on metabolism, organ function, physiology, and the five phase theory; and points out which aspects of these theories are fact based, which are metaphorical, and which are untrue. This enables students to readily understand Nei Jing metabolism and physiology, and to decide for themselves which aspects apply in reality.

Today's Chinese medicine disease syndromes are also explained. But in general the book follows the simple approach used in the Nei Jing. With each organ, a single main condition is cited, such as 'poor kidney function', then the signs and symptoms listed. This enables Western students to understand the condition, and also demonstrates how to communicate Chinese medicine to patients.

The book also analyses recent scientific ideas on how acupuncture may work, and describes its own 'intelligent tissue' hypothesis. This groundbreaking hypothesis is supported by objective experimental data and provides a lucid and plausible explanation of what the meridians are, what acupuncture is; and it also clearly describes the mechanism that enables acupuncture to correct organ malfunctions.

The book brings an unusual transparency to Chinese medicine, making the whole subject easier to understand.

Fletcher Kovich runs his own Chinese acupuncture practice in the UK.

Praise for Secrets of the Hidden Vessels

'The book is fascinating. And from the teaching perspective, it is a great tool to help students understand the organ functions. The book also uses an interesting approach to explain the mental and emotional factors in causing disease, which again will greatly assist in the teaching of this aspect of Chinese medicine.' - Brandon Fuller, Program Chair, East West College of Natural Medicine, Sarasota, Florida.

'We have come across many books on Chinese Medicine and particularly like this book's approach of blending the Western and Chinese understanding of the organs, to make it clear that both systems describe the same organs. There is a global paradigm shift in medicine, and the importance of Chinese Medicine in understanding the body and health plays a key role in the West's acceptance of alternative approaches to healthcare.' - Sam Patel, Joint Principal, The International College of Oriental Medicine (UK)

The Nei Jing consists of ancient Chinese scripts and is the foundation of Chinese acupuncture. But several factors make the Nei Jing, and also today's Chinese medicine, difficult to comprehend.Parts of the Nei Jing are fact based, parts are metaphorical and not intended to be interpreted literally, and other parts contain contradictory theories, which cannot all be true. Added to this is the problem that Chinese medicine concepts can seem incomprehensible to Western readers anyway.This book tackles these problems by relating Chinese medicine knowledge to today's physiology and identifying the overlap. The book also extensively analyses the Nei Jing theories on metabolism, organ function, physiology, and the five phase theory; and points out which aspects of these theories are fact based, which are metaphorical, and which are untrue. This enables students to readily understand Nei Jing metabolism and physiology, and to decide for themselves which aspects apply in reality.Today's Chinese medicine disease syndromes are also explained. But in general the book follows the simple approach used in the Nei Jing. With each organ, a single main condition is cited, such as "e;poor kidney function"e;, then the signs and symptoms listed. This enables Western students to understand the condition, and also demonstrates how to communicate Chinese medicine to patients.The book also analyses recent scientific ideas on how acupuncture may work, and describes its own "e;intelligent tissue"e; hypothesis. This groundbreaking hypothesis is supported by objective experimental data and provides a lucid and plausible explanation of what the meridians are, what acupuncture is; and it also clearly describes the mechanism that enables acupuncture to correct organ malfunctions.The book brings an unusual transparency to Chinese medicine, making the whole subject easier to understand.Fletcher Kovich runs his own Chinese acupuncture practice in the UK.Praise for Secrets of the Hidden Vessels"e;The book is fascinating. And from the teaching perspective, it is a great tool to help students understand the organ functions. The book also uses an interesting approach to explain the mental and emotional factors in causing disease, which again will greatly assist in the teaching of this aspect of Chinese medicine."e; - Brandon Fuller, Program Chair, East West College of Natural Medicine, Sarasota, Florida."e;We have come across many books on Chinese Medicine and particularly like this book's approach of blending the Western and Chinese understanding of the organs, to make it clear that both systems describe the same organs. There is a global paradigm shift in medicine, and the importance of Chinese Medicine in understanding the body and health plays a key role in the West's acceptance of alternative approaches to healthcare."e; - Sam Patel, Joint Principal, The International College of Oriental Medicine (UK)

Chapter 2. Chinese medicine metabolism and physiology

Translation of key Chinese medicine terms

One of the commonest Chinese medicine terms is also one of the hardest concepts to translate into English. This is the term chi 氣. As suggested by Unschuld, this concept was used in Chinese medicine when it was moving away from the notion that demons were responsible for causing illness.32 Instead it was now considered that environmental factors (such as wind, cold, or dampness) were responsible. These were referred to using the concept of chi. In this context, the term encompassed a range of ideas, such as: wind, breath, vapours, or the clouds in the sky. Its character 氣 is made up by placing the pictogram for “rising vapour” above the pictogram for “rice” or “millet”, so that the entire character means “vapours rising from food”. And these same “vapours” were also thought to be present in the body, either as a pathogen (such as the essence of “harmful wind” that had penetrated the skin) or as a nourishing element, such as the vapours extracted from the food we eat. The English translation of chi 氣 favoured by Unschuld is therefore “finest matter influences” or simply “influence”.

This concept was depicted nicely by Yü Shu, writing in 1067 (more than a millennium after the Nei Jing), when he said that the influences passing from the lungs and heart “resemble mist gently flowing into all the meridians”.33

As Unschuld points out, this concept is entirely different from the contemporary notion of “energy”, which is how chi is often translated in today’s Chinese medicine. But such a notion did not exist in ancient China and only obscures the term’s intended meaning. For this reason, this book follows Unschuld’s translation of chi as “influence”, so as to more accurately capture the term’s intended meaning.

How the body processes food

As mentioned above, the ancient Chinese had no concept of “energy” as we think of it today, yet they had intricate notions about how ingested food was converted by the organs to provide the resources the body needs.

Separating fact from metaphor and supposition

Some aspects of Chinese medicine were discovered through practical observation and are therefore fact based. But other aspects were created theoretically and tend to be either metaphorical, or based on unreliable suppositions about how the body might work—suppositions that were resorted to by necessity, since there was no useful information about the body’s internal anatomy and physiology.

Their notions of how the organs transform ingested food into useable resources are in the latter category. And when considered alongside today’s fact-based knowledge of anatomy and physiology (as far as it has so far progressed), most of these ancient Nei Jing ideas are simply untrue.

On the other hand, the Nei Jing notions of the signs and symptoms that occur when any organ is stressed, these are all factual—since they were discovered through practical observation. And any other aspect of Chinese medicine similarly discovered tends to be factual. The metaphorical and unreliable (or more bluntly, “untrue”) elements tend to be their theoretical explanations of how those signs and symptoms are produced. And when striving to understand Chinese medicine, it is important to be clear in your mind about which aspects are factual, metaphorical or untrue.

Overview of Chinese medicine metabolism

Food and liquids are taken in by the stomach, which extracts “food influence” from them. The lungs then extract “clear influence” from the air to create a third type of vapour which nourishes the lungs and heart and enables them to carry out their functions.

Liquids are also extracted from ingested food and transformed into blood. In ancient China, there was no notion of a separate blood circulatory system, nor of the heart acting like a pump (p.ref). Instead the meridian network was the only known circulatory system, so it was natural to assume that all substances circulated within it.34 Therefore, the blood was thought to circulate within the meridians, while the various types of influence also travelled either within (along with the blood) or outside of the meridians, much like a vapour or mist encircling each meridian.

Once food influence was extracted by the stomach, it then divided into two parts. The food influence (like all other influence) was thought to be a vapour-like substance, and this contained some vapours that were more active and aggressive (the yang portion) and some that were more restful and supportive (the yin portion). The supportive portion of the vapour was known as “constructive influence” and this circulated within the meridians to every part of the body, having a nutritive action. Whereas the more active portion of the vapour was known as “defensive influence” and this circulated on the outside of the meridians and warmed the muscles and skin.

The purpose of the blood was seen as purely nutritive. The blood provided nutrition to every part of the body—the muscles, joints, and organs—which meant there were two factors that nourished the body, the blood and the constructive influence, both flowing together in the meridians.

External pathogens, known as “harmful wind”35 or “uninvited guests”, would enter the body through the skin. In form, these were similar to the vapours the digestion extracted from food and would travel through the body in the same way. The “defensive influence” had the role of warming the skin and muscles, and as long as the defensive influence was strong enough, then the harmful wind would not be able to penetrate the skin. But if a person’s defensive influence was depleted, the harmful wind could penetrate. The wind (in the form of a “harmful vapour”) would reach the meridians and lodge there, causing local discomfort. If not cleared by treatment, this “harmful vapour” would then travel along the meridians and eventually lodge within the organs, causing serious illness.36

There was also thought to be a constitutional influence (another type of vapour) which was passed on to us from our parents. It was thought to be stored in the kidneys37 and circulated to the organs, so as to provide an extra vital stimulus that the organs need to function properly. This influence, while stored in the kidneys, may be supplemented each day by the vapours extracted from ingested food.

The Chinese terms for these various “influences”

The Chinese term for food influence is gu chi 穀氣. Alternative translations are “grain influence” or “valley influence”.

The term for clear influence (extracted from the air we breathe) is qing chi 清氣.

The term zong chi 宗氣 refers to the influence formed in the lungs and heart. Zong chi is variously translated as “chest influence”, “stem influence”, “pectoral influence”, or “gathering influence”.

The term for constructive influence is ying chi 營氣, which is also translated as “nourishing influence” or “camp influence”.

The term for defensive influence is wei chi 衛氣, which is also translated as “protective influence” or “guard influence”.

The term used for the constitutional influence varied between different texts. In the Su Wen and the Ling Shu, the term jing chi 精氣was used, which is translated as “essence influence”; or the term jing 精was also used alone and is variously translated as “pure essence”, “seminal essence”, “congenital essence”, “acquired essence”, or simply “essence”.38 But in the slightly later Nan Jing, the term yuan chi 原氣 was now used, which is translated as “original influence” or “primary influence”.

The above influences are present in the meridians, which circulate them; and when combined together they were known as “true influence”. The Chinese term zhen chi 真氣 was used to describe true influence.39

The terms for body liquids

The “liquids” in the body were termed the jin 津 liquids and the ye 液 liquids. These were defined as follows.

Extract from Ling Shu, Chapter 30

That which is released to flow out of the skin structures, when a person sweats profusely, that is what is called “jin liquid” … When grains enter the body and fill it with the [influences], then a viscous liquid pours into the bones, enabling the [joints] to bend and stretch. The [influences] flow out to fill the brain with marrow and they provide the skin with dampness. That is what is called “ye liquid”.40

Hence, the jin are the finer liquids, and the ye are the more viscous liquids, including marrow, and even the brain, since “marrow” (being a product of the kidneys) was thought to fill up the spinal cord and also the brain (p.ref).

Summary of contemporary metabolism

None of the above terms can be accurately translated into the terms used in contemporary...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.10.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Alternative Heilverfahren |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Lebenshilfe / Lebensführung | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Naturheilkunde | |

| Schlagworte | acupuncture • Chinese Medicine • Nei Jing |

| ISBN-10 | 1-9164830-5-4 / 1916483054 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-9164830-5-7 / 9781916483057 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich