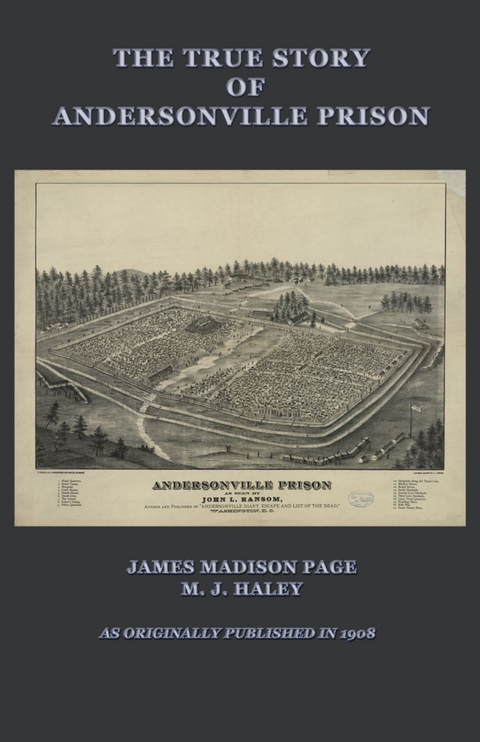

The True Story of Andersonville Prison (eBook)

256 Seiten

Digital Press (Verlag)

978-1-58218-417-3 (ISBN)

During the Civil War, James Madison Page was a prisoner in different places in the South. Seven months of that time was spent at Andersonville. While there he became well acquainted with Major Wirz, or Captain Wirz, his rank during Page's confinement.

Page takes the stand that Captain Wirz was unjustly held responsible for the hardship and mortality of Andersonville. It is his belief that the Federal authorities must share the blame for these things with Confederate authorities, since they were well aware of the inability of the Confederacy to meet the reasonable wants of their prisoners of war, as they lacked supplies for their own needs and since the Federal authorities failed to exercise a humane policy in the exchange of those captured in battle.

During the Civil War, James Madison Page was a prisoner in different places in the South. Seven months of that time was spent at Andersonville. While there he became well acquainted with Major Wirz, or Captain Wirz, his rank during Page's confinement.Page takes the stand that Captain Wirz was unjustly held responsible for the hardship and mortality of Andersonville. It is his belief that the Federal authorities must share the blame for these things with Confederate authorities, since they were well aware of the inability of the Confederacy to meet the reasonable wants of their prisoners of war, as they lacked supplies for their own needs and since the Federal authorities failed to exercise a humane policy in the exchange of those captured in battle.

CHAPTER II

A SPRINT AND A CAPTURE

Our regiment moved from Fairfax Court House on June 25, 1863, and when Hooker’s army began its movement to intercept Lee, Stahl’s division of cavalry was made a part of the Army of the Potomac at Edward’s Ferry.

Kilpatrick succeeded Stahl in the command of the cavalry division and Col. Geo. A. Custer was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general from the rank of captain on Pleasanton’s staff, and took Copeland’s place in command of the Michigan Brigade, consisting of the First, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Michigan Cavalry regiments. General Custer was first seen by us at the battle of Hanover, Pennsylvania, June 30, 1863, which was the first time that the Sixth, our regiment, was under fire, except on the skirmish line at long range. At the battle of Gettysburg General Custer ordered Captain Thompson, of my company, to charge Gen. Wade Hampton’s cavalry in a narrow lane on the eve of July 2, the second day of the fight.

A most desperate hand-to-hand conflict ensued. We went into this charge 77 men, rank and file, and next morning my company could rally but 26. In less than one-half hour we lost in killed, wounded, and captured, 51 men. Captain Thompson was wounded, and S. H. Ballard, our second lieutenant, whose horse was shot under him, was captured, and remained a prisoner to the close of the war. I received a slight saber cut on the head, but, strange as it may seem, I knew nothing about it until the next morning, when on being awakened from a few hours’ sleep I felt a peculiar smarting sensation on my head and found my hair matted with blood. A thorough washing revealed a slight cut on the top of my head, a wound about two inches long and only deep enough to draw blood. During “piping times of peace” at home it would have been considered quite a wound and I would have had the neighbors taking turns to look at it; but on the field of Gettysburg I would be laughed at for my pains if I showed it to any one, and I don’t remember of any one knowing anything about it but myself. Moreover, under the burning sun of that 3d of July it bothered me considerably, but I did not report it to the surgeons. We were too busy fighting the “Johnnies.”

On July 4, at 10 a. m., our division being in advance, we marched from the sanguinary field of Gettysburg to intercept the enemy, who was retreating along the South Mountain road toward Williamsport. We marched by way of Emmettsburg up the road to Monterey, a small place as it appeared at night on the top of South Mountain range. On the 5th of July we had some skirmishing with the enemy’s cavalry, and encamped that night at Boonsboro, Maryland.

On the 8th our regiment had an engagement with the enemy’s cavalry on the Hagerstown road near Boonsboro, and three of our company were wounded. We were also engaged July 11, 12, 14, 20 and 24.

On July 14 our regiment was sharply engaged at the battle of Falling Waters, and had a number killed and wounded. Among the killed of the Sixth Michigan Cavalry were Capt. David G. Boyce and Maj. Peter A. Webber. I may be pardoned, perhaps, in quoting what was said about our brigade at this battle, and particularly of the Sixth Michigan Cavalry, of which I was a member. The New York Herald contained the following:

“Hearing that a force had marched toward Falling Waters, General Kilpatrick ordered an advance to that place. Through some mistake, only one brigade, that of General Custer, obeyed the order. When within less than a mile of Falling Water the enemy was found in great numbers and strongly entrenched behind a dozen crescent-shaped earthworks. The Sixth Michigan Cavalry was in advance. They did not wait for orders, but one squadron, Companies C and D, under Captain Boyce (who was killed), with Companies B and F, led by Major Webber (who was killed), made the charge, capturing the works and defenders. It was a fearful struggle, the rebels fighting like demons. Of the 110 men engaged on our side, but 30 escaped uninjured. This is cavalry fighting, the superior of which the world never saw.”

On this campaign our regiment had a strenuous time of it. For seventeen days and nights we did not unsaddle our horses except to readjust the saddle-blankets.

The next trouble we had was when we crossed the Potomac into Virginia in the rear of Lee’s army and encountered Stuart’s cavalry at Snicker’s Gap, on July 19. The charge was simultaneous and I came near “passing in my checks,” for I was knocked from my horse in the charge and was run over by half our regiment. I was stunned and badly bruised, but not cut. When I came to I was glad to find that my sore head was still on my shoulders. I was soon mounted, and our regiment went into camp.

We remained there next day awaiting rations, and, while riding from the quartermaster’s tent to my company, I crossed a field that was overgrown with weeds and briers and ran against a gray granite slab. I dismounted, and pulling the briers aside, I saw that it was a gravestone. The inscription stated the man’s name and age, which I have forgotten; the date of his death at an advanced age, in 1786, and concluded with this quaint inscription:

“Man, as you are passing by,

As you are now, so once was I;

As I am now, so you must be;

Turn to God and follow me.”

This affected me deeply. The thought occurred to me that when in life (for he died but three years after the Revolution) how little he expected that the time would come when his beautiful domain and his bright sunny Southland would be devastated and laid waste by an invading army of his own countrymen!

From June 30 to September 21, 1863, our regiment participated in seventeen skirmishes and battles On September 14, at Culpeper Court House, General Custer was wounded and the command of the brigade devolved upon Colonel Sawyer of the First Vermont Cavalry, which was brigaded with us at the time.

On taking command Sawyer seemed to think that the war had been going on long enough, and he decided to end it at once. Like Pope, his headquarters were in the saddle. “Up and at them” was his motto. He wasn’t, as yet, even a brigadier by brevet, but visions of the lone star on his shoulders, I presume, took possession of him. “Dismount and fight on foot!” was the ringing order from the Colonel on September 21, at Liberty Mills, on the Rapidan, and, as had been my habit, I snapped my horse to a set of fours of led horses, and borrowing the gun and cartridge-box of the soldier in charge of the horses, I joined my company commanded by Capt. M. D. Birge. We crossed the bridge and deployed in a cornfield on the left of the road. I was on the extreme left, and paid very little attention to the regular line, as I was an independent skirmisher; but as soon as I found that more than twenty of us were separated from the line by drifting into an open ravine for better protection, I was a trifle tamer than when I started out a half hour previous. On the right the corn was cut and stood in shocks, and while the line advanced up the ravine I ascended the ridge, keeping under cover as well as I could behind the corn shocks. When I reached the top of the elevation I was completely staggered to see several hundred mounted Confederates advancing toward us, platoon front, as if on parade. There was no time to lose, for the lead was crashing through the shock that I was behind, at a fearful rate, and how I escaped with only a rip in my blouse near my left elbow is more than I shall ever know. I had possibly three hundred yards to run to reach the boys, now under command of Lieutenant Hoyt. I safely got where they were without being hit, but the time I made in doing so would have been creditable to the fleetest jack-rabbit.

I reported the danger we were in. All this time a mounted staff-officer a few hundred yards back of us was shouting himself hoarse, “Advance, men, advance!” “I cannot fall back when ordered to advance,” said Hoyt. “Lieutenant, if you do not we are lost,” was my reply. The soldier will at once realize the embarrassment of my position in advising a retreat. It savors so much of the “white feather.” It is always well enough for the inferior to advise a forward movement, even though the superior ignores the advice, but it is a ticklish thing to advise retreat — even the word “retreat” is dangerous. I knew the danger, because I saw it. The ground was undulating, and neither Lieutenant Hoyt nor the frantic staff-officer could see the advancing body of Confederates. “We will be surrounded and scooped up in less than five minutes,” said I. “I cannot help it,” replied Hoyt, “I must obey orders. Forward!”

We advanced perhaps a dozen rods, when the enemy was upon us. A Minie ball struck Hoyt in the shoulder and he was down. The charge followed. We received no more bellowing orders from the elegantly attired staff-officer. He at once adopted Falstaff’s advice about “discretion being the better part of valor,” and the skirts of his beautiful dress-coat would have made tails for a kite. The speed with which he reached a safe rear was of the fleetest. I can imagine his report to Colonel Sawyer, commanding brigade. It ran something like this: “They were captured because they did not obey my orders. I remained as long as possible, but was obliged to fall back.”

I tried to get Hoyt away, but he was so badly hurt that he begged to be left on the field. I then gave...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.7.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► 20. Jahrhundert bis 1945 |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | American Civil War • andersonville prison • Civil War Prison • Civil War Starvation • confederate prison • Henry Wirz • union prisoners |

| ISBN-10 | 1-58218-417-8 / 1582184178 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-58218-417-3 / 9781582184173 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 544 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich