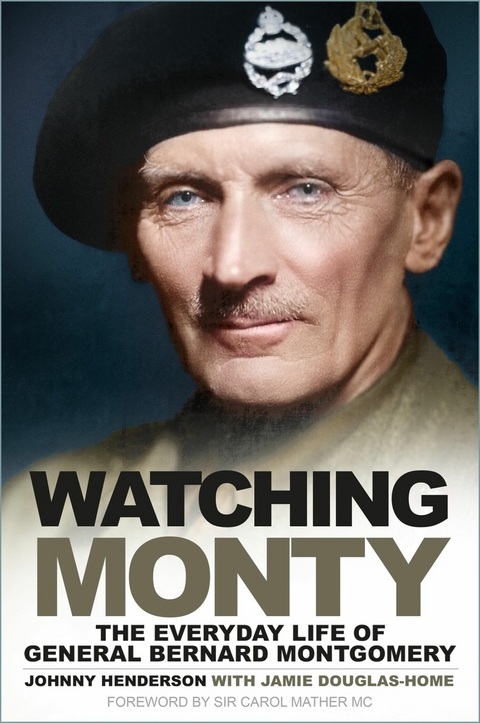

Watching Monty (eBook)

224 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-9576-7 (ISBN)

ONE

WITH THE EIGHTH ARMY IN THE DESERT

NOVEMBER 1942–JUNE 1943

When I joined Monty’s Tac HQ, the Eighth Army was chasing Rommel’s retreating forces into Libya and the Allied invasion of Morocco and Algeria under Eisenhower had just begun. So the depleted German and Italian Army was now facing a war on two fronts.

The Libyan port of Tobruk was recaptured on 12 November 1942. Then Monty won an important victory on 17 December at El Agheila on the coast road in between Benghazi and Tripoli, where some Eighth Army soldiers had been twice before. Monty then prepared to advance on Tripoli. We entered the Libyan capital on 23 January 1943 and stayed there for a few weeks to open up the harbour and build up our supplies for the next stage of the journey towards Tunis.

While we were in Tripoli, Rommel’s attention turned to the other Allied front, and he attacked the Americans. The First Army was in considerable danger in late February, so Alexander, Eisenhower’s Deputy Commander-in-Chief, asked Monty to put some pressure on the Afrika Korps from the other direction. Monty moved fast, and Rommel soon called off his assault on the Americans.

Monty guessed that Rommel’s sights would now be set on the Eighth Army. As expected, the German commander attacked at Medenine inside the Tunisian border on 6 March. Rommel’s forces were driven back, losing 52 tanks, but Monty declined to follow as the Germans withdrew. He knew that Rommel would stop at the great defensive obstacle, the Mareth Line, south of Gabes, which had been constructed by the French in case of an Italian attack from Tripolitania. Monty knew that the Mareth Line would be difficult to pierce and was ready for a hard fight. There were many anxious moments during the battle of a week, but a concerted blitz of air and ground forces on 27 March eventually won the day.

Monty, dressed in his favourite casual attire. (IWM BM20753)

It was clear that the war in North Africa would finish soon, as the enemy was now hemmed in on both sides. Monty won a stiff one-day battle at Wadi Akarit, north of Gabes, on 6 April, and the Eighth Army joined up with the Americans, who were moving east from Gafsa, on 8 April. The city of Sfax was captured two days later. On 7 May the British forces took the capital, Tunis, and the Americans captured the port of Bizerte on Tunisia’s northern tip. Six days later, on 13 May, all enemy forces surrendered and the Desert War was over.

My Arrival at the Eighth Army Tac HQ

It was 10 November 1942 and the historic battle of Alamein was over. The pursuit of the retreating German Army along the Egyptian coast towards the Libyan border was now on.

Left to right: John Poston, Freddie de Guingand, Monty and the author, Johnny Henderson, in front of Tac HQ. (Eton College Library)

My regiment, the 12th Royal Lancers, was part of the 1st Armoured Division and was not involved. So, for once, there was peace and quiet, but we always had to have our wirelesses ready for any orders from our squadron or, less likely, from regimental headquarters. My corporal arrived and said that there was a message to report to the colonel. We did not like these sorts of message as they invariably meant that we were to be sent on a nasty mission. The colonel, George Kidston, however, came quickly to the point, ‘You are to go off to be ADC to the Army Commander.’ ‘Help, you mean, Monty’ said I. ‘Yes,’ he replied. After a few minutes’ thought, I asked if I could take Charlie Saunders, my wonderful soldier servant and, by now, friend with me.

Sidney Kirkman, who thought the author’s new appointment was temporary. (Eton College LIbrary)

So we set off, full of apprehension, and got to the Eighth Army Tac HQ near Mersa Matruh about 4.30 p.m. As John Poston, his other ADC, was out with Monty, I waited in the mess tent, feeling mighty lonely. Then a senior officer walked in, whom I later discovered was Brigadier Kirkman. He said, ‘Hello, are you the new temporary ADC?’ That made me wonder how temporary my new appointment was to be!

Monty and John soon arrived. John introduced me to Monty, who, after a very short conversation, said, ‘I will see you at dinner. John will look after you.’ John had been ADC to General ‘Strafer’ Gott, who had been killed in an aeroplane crash soon after taking over command of the Eighth Army. Monty, of course, was Gott’s successor.

Monty, Freddie de Guingand, Bill Williams, John and I dined together that evening. Dinner had hardly started when Monty began to fire questions at me. ‘How long have you been in the desert? Why did you join the 12th Lancers? Where did you go to school?’ ‘Oh, Eton,’ he exclaimed, ‘and what do you say to that as John was at Harrow?’ Well, I trotted out the usual old response: ‘The one good thing about Harrow was that you could see Eton from it. Now, John, what about that?’ That was the taste of dinner every night with Monty. He relaxed for an hour by starting an argument with us. We soon learnt we had to answer back.

I was glad when that ordeal was over, but, later that evening, John Poston gave me an invaluable bit of advice – to always tell the truth to Monty. If you did not and he found out, that was likely to be the end of you. So, John and I talked into the night in our beds in the tent let down off the side of Monty’s caravan. John assured me that life there was much easier than I might have imagined.

Key Staff at Monty’s Tac HQ in North Africa

Monty surrounded himself with a small number of key personal staff at his desert Tac HQ. I soon realised how efficiently they went about their business and also what a good picker of men the Eighth Army commander was.

Freddie de Guingand, who was 42 and then a brigadier, was already at Eighth Army HQ when Monty arrived in Egypt. Monty knew him previously and had always admired his ability. So he interviewed Freddie immediately and made him his Chief of Staff. Monty had decided to have a small forward HQ (Tac HQ) in order to be in close touch with the fighting line. He was determined that his experience as a divisional commander during the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940 – communications broke down completely – should not be repeated. Also, as he was away from Main HQ, he did not get bogged down with unnecessary detail. Therefore Freddie was in charge of all that went on at Main HQ.

Bill Williams, Monty’s head of intelligence. (Eton College Library)

Freddie was mighty clever, very quick and full of ideas – many of which Monty took on as his own. He lived on his nerves and consequently had health problems. But, unlike Monty, he appreciated the good things in life. As Freddie completely lacked pomposity, everyone, and I mean everyone, admired and loved him.

Monty had the amazing gift of simplifying any problem and making himself absolutely clear. So, when he made a plan, he always left Freddie to make the necessary arrangements. Freddie’s talent for thinking of everything and putting a plan into action fast still makes the mind boggle. But, it made a huge difference that he was always cheerful and a friend to one and all.

Monty knew how lucky he was to have Freddie. Although he did not often sing men’s praises, he did as far as Freddie was concerned. In fact, he later wrote, ‘He was a brilliant Chief of Staff and I doubt if ever before such a one existed in the British Army or will ever do so again.’

Furthermore, because he was friendly with the American commander, Eisenhower, and Bedell Smith, Ike’s Chief of Staff, Freddie smoothed over many a difficult situation. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that had it not been for Freddie’s intervention, Monty might well have been relieved of his command in Europe in the tricky period in the autumn of 1944 after the liberation of Brussels.

Freddie spent half his time at the Tac HQ in the desert and had a caravan there. He would sit up in the evenings playing his favourite card game, chemin de fer, for small amounts of money. I never thought that a person in his position would become such a good friend in so short a time.

Brian Robertson, a very efficient Q. (Eton College LIbrary)

E.T. ‘Bill’ Williams, also a brigadier, was only 29 years old when he became Monty’s Chief Staff Officer of Intelligence. But, as he was already at Eighth Army HQ, he was well known to Freddie. When the war started he was a don at Oxford and left to join the King’s Dragoon Guards. Bill was a brilliantly clever fellow with a lovely dry sense of humour and told his stories in a lugubrious manner. He proved his value soon after Monty’s arrival in Egypt by predicting when and where the Germans would attack at Alam Halfa. Every night he would wire John Poston or myself the all-important positions of the two German Panzer Divisions and their 90th Light Division.

In the early days Bill always took the press briefings. Immediately after the victory at Alamein, a huge crowd of reporters rushed round to his caravan and an American journalist said, ‘Gee, this is the greatest thing that has happened in this area since the Crucifixion.’ Bill replied, ‘And it only took four to report on that.’

Bill had Monty’s ear and the Army Commander relied on what he had to say and would listen intently. He played a huge part in the Eighth Army’s victories. He came to see Monty once or twice a week and invariably stayed the night. Bill went back to England with Monty and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.5.2005 |

|---|---|

| Co-Autor | Jamie Douglas-Home |

| Vorwort | Carol Mather |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Mathematik / Informatik ► Informatik | |

| Schlagworte | Eisenhower • El Alamein • General Bernard Montgomery • Imperial War Museum • johnny henderson • King George VI • luneberg heath • Monty • montys adc • sir alan brooke • tac hq • war anecdotes • western desert • Winston Churchill |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-9576-3 / 0752495763 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-9576-7 / 9780752495767 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 54,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich