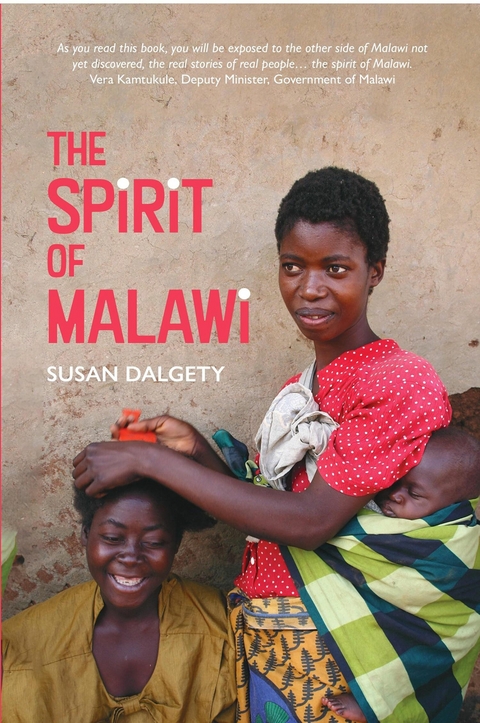

The Spirit of Malawi (eBook)

228 Seiten

Luath Press (Verlag)

978-1-80425-147-8 (ISBN)

SUSAN DALGETY and her husband, an economic researcher, spent six months in Malawi from May 2019, interviewing scores of people and researching the country's history and its future prospects. During her stay, she filed a weekly 'Letter from Malawi' for The Scotsman. As the former head of communications for Lord McConnell, when he was First Minister of Scotland (2001-06), her first trip to Malawi was to set up the first official visit by the Scottish government, and help develop a bi-lateral co-operation agreement between the two countries, which remains in place today. She was previously chief writer on the Edinburgh Evening News, deputy leader of Edinburgh City Council and Director of Communication for Scottish Labour, as well as editor of the Wester Hailes Sentinel - Scotland's ground-breaking community newspaper during the 1980s and '90s This is her first book.

CHAPTER 1

The spirit of Malawi

MALAWI IS A country of children. They tumble out of simple school blocks, their uniforms dusty with Africa’s red soil, smiling broadly as they head home after a few hours of learning English and maths. Babies cling for dear life to the backs of girls barely older than the child they are carrying. Dark-eyed toddlers, wearing t-shirts discarded by rich European families and flown 5,000 miles to be sold in Malawi’s roadside markets, sit quietly with their mothers, occasionally suckling on a casually offered breast. Footballs made of tightly bound plastic bags soar through the air, chased by scores of bare-footed little boys.

‘Azungu, azungu (white people),’ children cry delightedly when they spot white strangers in their township or village.

More than half of Malawi’s 18 million population is under 18 years old. The statistics, gathered by the international agencies that hover over Malawi like a benevolent, if mildly censorious aunt, paint a depressing picture of a generation of children at risk from stunted growth, functional illiteracy and premature death. But the reality is so much more alive and hopeful than UNICEF’s carefully researched infographics and strategic plans suggest. A girl born today can expect to live to 67 years – in 1960, she would have likely died before she was 40.

This small landlocked country does not have the natural riches found elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. There is very little gold, no copper or titanium. Oil may lurk deep in Lake Malawi, but no one, as yet, has exploited it. Malawi’s children are its most precious resource.

Busisiwe (38) has just returned from a business trip to Johannesburg. She endured 48 hours on a crowded bus, travelling through Mozambique to South Africa so she could buy hospital blankets to sell on her return. Her modest medical supply business, which she runs from her late grandmother’s rambling home on the edge of Blantyre, supports her and her six-year-old daughter. Her income also helps support her 15 nieces and nephews, many of whom live with Busisiwe, and two of her six siblings.

‘Children are our life,’ laughs Busisiwe as she picks up a stern-faced toddler. Brenda has just turned one and is the youngest of the Chimasula clan. ‘They are expensive, school fees are our biggest headache, but we love all our children. They are very important in our culture.’

Malawi is a modest country. It is a narrow strip of land along the East African Rift Valley, squeezed between Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia. It is around 560 miles long and 150 miles across at its widest part, similar in size to Bulgaria, and nearly 50 per cent bigger than Scotland. More than one-fifth of the country is taken up by Lake Malawi which, at over 360 miles long, is Africa’s third-largest freshwater lake. Its beautiful beaches and gently lapping water are a magnet for rich, white gap year students, eager to experience the ‘real’ Africa. It is the heart of the country, providing fish to eat, water for irrigation and power and a home to one of the world’s most important collections of freshwater fish. There are around 700 species of cichlids, the colourful fish that fill home aquariums, more than any other lake in the world. It is also, argue some, where human life began. Standing alone on a quiet beach anywhere along the lake’s western shore, it is easy to imagine that this is where the story of our world started. That this tiny country, one of the poorest in the world, is our home village.

‘Malawi is different,’ says Govati Nyirenda, one of the country’s first professional photographers and a well-travelled man. He pauses, then his rich, brown voice picks up his theme. ‘To my mind, a Malawian is someone who loves people, who welcomes them. Having visited some other countries in Africa, I feel that we are different to most of the nationalities around this part of Africa. We are kinder, open-hearted people, we welcome foreigners. I know the slogan “Warm Heart of Africa” is for tourists, but I think it is true,’ he laughs, slightly embarrassed at the cliché.

Malawi’s history is not chronicled in the same way as the stories of European civilisations. There are no soaring cathedrals. No ancient texts or printed volumes of plays and poems from 400 years ago. Stories are carefully passed down from generation to generation, woven into the fabric of daily life over centuries. Agogos (grandparents) tell tales of great chiefs and bloody battles, of wizards and lions, deadly snakes and magic dancers.

There is some hard evidence of very early life in Malawi. The rock paintings at Chongoni, a UNESCO World Heritage site, were drawn by hunter-gatherers, some dating as far back as the 6th century BCE. Malawi’s first known tribe was the legendary Akafula people. They are described as people of short stature with copper skin. They lived a peaceful existence along the shores of Lake Malawi, happily mingling with sporadic waves of Bantu-speaking people who travelled to the area from the 1st century.

It was not until the 13th century that another, more determined, influx of Bantu-speaking people from the north and west, including the Congo area, settled permanently in the region. This new population were farmers, bringing with them yams and bananas, as well as iron tools. They also introduced a system of formal government, and in 1480 the Bantu tribes united several settlements under one political state, the Maravi Confederacy, which at its height included large parts of present-day Zambia and Mozambique, as well as Malawi.

Govati recalls stories from these peaceful times, before the arrival of Arab slave traders and white colonialists. ‘Our old parents [ancestors] lived a peaceful life, where people looked after each other. For example, in my father’s village in the north, the women would prepare food together, and eat together. They would also send it to the lakeshore, where most of the men lived and worked, so they could eat. It is that ancient community that makes me feel Malawian.’

That community, which had started to develop more productive farming methods and to grow a wider range of crops, including cassava and rice, was largely made up of three tribes: the Anyanja, the lake people, the Atumbuka in the northern region and the Achewa who lived in the central plateau. Today, the Chewa are Malawi’s biggest tribe. Their increasingly prosperous, agrarian idyll was shattered forever by a series of invaders. Portuguese traders arrived in the 16th century, first to trade in ivory and gold, and later in people. The height of Malawi’s exposure to the slave trade was in the 19th century, when Swahili-speaking Arabs, and the Yao people from what is now Mozambique, stole thousands of healthy young men and women to sell in the slave markets of Zanzibar and Mombasa.

The Yao settled along the lakeshore and in the Shire Highlands in the south, bringing with them their Islamic faith. Today, around one in seven of Malawi’s population are Muslim. From the south came the Ngoni people, armed refugees fleeing from the Zulu states. They settled in the north and the central regions after making peace with the Tumbuka and Chewa tribes. Then came the white missionaries. The first, and most famous, was Dr David Livingstone, a Scottish missionary, explorer and humanitarian, who first visited in 1859. His influence, and that of the Scottish missionaries who followed in his wake, remains visible in Malawi today. The country’s oldest city, and its commercial heart, is named after Livingstone’s birthplace – Blantyre, a small former mill town in central Scotland. Its most influential denomination, the Church of Central Africa Presbyterian (CCAP), is a sister church of the Church of Scotland and, since 2005, there has been a formal co-operation agreement between the governments of Scotland and Malawi.

The SMP and its sister organisation, the Malawi Scotland Partnership, support hundreds of civil society links. This relationship, built on a high-minded but practical principle of mutual solidarity, is rooted firmly in a common vision of humanity. ‘Somehow, I feel that many of the donors just pull us backwards,’ muses Govati. ‘I like what Scotland does with Malawi. She is not a donor, Scotland is a partner. We exchange experiences, we exchange skills and friendship.’ He stops for a moment, then reworks an old saying in his own words, ‘You should teach someone to fish by giving him fish nets, so he can catch the food himself. Don’t give him fish.’

The Scottish missionaries, who were quickly followed by the Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa and Roman Catholics from France, gave Malawi a new God to worship, as well as basic formal education and rudimentary health care in some areas. They also opened the door to colonialism, white farmers and businessmen eager to exploit the fertile lands of Malawi.

In 1891, the British established the Nyasaland Districts Protectorate, shortened in 1907 to Nyasaland. Malawi was now under the ‘protection’ of the British state, their new ‘chief’ was King Edward VII, and their new village elders the civil servants of the colonial administration. This new tribe of white settlers built roads and railways,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Reisen ► Reiseführer |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80425-147-X / 180425147X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80425-147-8 / 9781804251478 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich