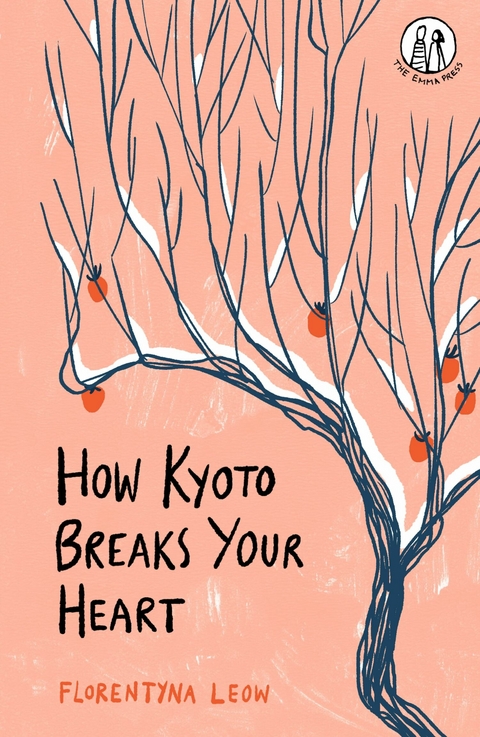

How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart (eBook)

152 Seiten

The Emma Press (Verlag)

978-1-915628-01-5 (ISBN)

Florentyna Leow is a writer and translator. Born in Malaysia, she lived in London and Kyoto before moving to Tokyo. Really, though, she lives on the internet. Her work focuses on food and craft, with an emphasis on under-reported stories from rural Japan, like English Toast (neither English nor toast), a shrine dedicated to ice, and Japan's rarest citrus. She cannot go five minutes without thinking about food. How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart is her first book. She can be found @furochan_eats on Instagram and Twitter, or at www.florentynaleow.com

Florentyna Leow is a writer and translator. Born in Malaysia, she lived in London and Kyoto before moving to Tokyo. Really, though, she lives on the internet. Her work focuses on food and craft, with an emphasis on under-reported stories from rural Japan, like English Toast (neither English nor toast), a shrine dedicated to ice, and Japan's rarest citrus. She cannot go five minutes without thinking about food. How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart is her first book. She can be found @furochan_eats on Instagram and Twitter, or at www.florentynaleow.com

Persimmons

Persimmon blossoms emerge in June, petite and cream-coloured, as though clusters of buttery pursed lips have sprouted all over the tree – or so I’m told. I can’t recall the persimmon tree in this garden ever flowering. Bright green leaves one day, fruit the next – they seem to blink into being overnight as June’s rainy season subsides, oval lumps swelling over the summer months until blushing orange in autumn, like a thousand little suns festooning the tree. Visiting crows peck away at persimmons on the highest branches. Some ripen all too quickly, landing in fragrant, messy puddles in the undergrowth, a feast for wasps and songbirds alike.

It is early October now, a warm, sunny afternoon with a dreamlike cast, and we’re harvesting persimmons. The tree is still lush and green; in a few weeks it will be bare, scattering leaves in a brilliant carpet of mottled tangerine and vermillion. She shimmies up the ladder and snips away at the fruit-laden boughs with red shears. I catch them – mostly – and prise the persimmons from the branches by their calyxes. If I close my eyes I can still hear our peals of laughter, her yelps and curses as some fruit falls into the roof gutters. Oh fuck! I can feel myself shaking with laughter. I look up. Her hair glints in the sun.

When we have harvested close to three-quarters of the tree we call it a day. The persimmons spill out across the veranda by the hundreds, far more than we can reasonably eat by ourselves. We’ll pile them up in a corner, but for now we make persimmon angels: arms spread, surrounded by abundance. Autumn sunshine streams in through the glass of the sliding doors. My heart catches a little, as though there’s a glass splinter inside. I’m already weeping for the moment as it slips away. I’m happy. It hurts. I think this is where I’m supposed to be.

This is how I remember her still: luminous, laughing, haloed by sunlight and sunset-coloured fruit.

■ ■

I spent two years in Kyoto during my twenties, sharing a house with a friend I’d known from university in London. She contacted me a few months after I’d arrived in Japan to ask if I wanted to work remotely with her at her current job and also move in with her. She would be asking her housemate (whom she couldn’t stand) to leave. I didn’t know her particularly well, but I knew I enjoyed being around her, admired her relentless drive, her sardonic wit and colourful stories, her taste in ceramics, her depth of knowledge on traditional art and culture – and I would have jumped at any opportunity to leave my job in Tokyo. It made sense. I had a way out of the retail job I hated, and she would have a colleague to share her increasing workload with and a new housemate.

The job itself was mundane: customer services, consisting largely of emails to and from clients wanting to travel to Japan on guided tours. But I genuinely loved the products I sold, and for all their flaws the company management had a real knack for attracting good-hearted people with fascinating backgrounds, and creating an unusually tight-knit working culture where everyone could more or less understand the role they played and why it was essential. In other words, even though it was poorly paid and I was ultimately replaceable, I knew the work really meant something to the company, and it provided – at least initially – that sense of purpose I craved. It was the only full-time position I had actually ever wanted, so I was determined to make it work.

Adding to the novelty of the situation was the house I shared with her. It was a single-storey building ensconced in the northeastern suburbs below Mt. Hiei – more of a hill than a real mountain – and rented from a couple living in upstate New York. From the nearest station, you made your way through a shotengai1 and up a hill, through a few slender, unnamed lanes and turnings before arriving at a nondescript-looking house encircled by a modest garden space, which for the most part lay unused. The waist-high gate to the property tended to stay ajar, more there to mark a boundary than provide security.

Like many houses in Japan, it was poorly insulated, with thin walls that shook and rattled whenever an earthquake shuddered through the city. The floorboards creaked and complained, especially in the deafening silence of 3am when I stumbled my way to the toilet on the other side of the house. Summer invariably saw several cockroaches the size of golf balls scuttling across the kitchen floor, and winter had us huddling close to fume-spewing kerosene heaters which only ever warmed the room to a tepid temperature at best.

None of that mattered. I loved the house, and as far as I remember she did too. My bedroom window faced the front garden and its unruly carpet of weeds, and I could see Mt. Hiei most days, mist clinging to its silhouette in the mornings. At the other end of the house, the kitchen overlooked a spacious and endlessly abundant community garden, where local residents planted all manner of delicious things year-round – bitter gourd, cucumber, aubergine, daikon – and beyond the surrounding suburbs more mountains lay in the distance. I hadn’t realised I missed looking at the vast bowl of sky above until I left Tokyo and its tall buildings, and there were many days my heart would ache with pleasure just looking out of the kitchen window.

What I loved most about this house, though, was the persimmon tree.

At the heart of the house was a room lined with tatami mats, which my friend used as her bedroom. It was bordered by an engawa – a kind of veranda, an L-shaped, metre-wide corridor running along the edges of this room – and looked out into the central garden. A few pine trees and bushes dotted a space covered mostly with grasses. On the right, a Japanese maple extended its spidery branches over a petite nandina bush that had dark glossy leaves, and bright red berries in winter. To the left, the persimmon tree: relatively young and sprightly, a knobbly lichen- and moss-furred trunk stretching languorously towards the sky. It had rarely been pruned and it towered above the roof, ending in a spray of skinny branches at its crown, like a halo of flyaway baby hair.

Despite growing up in a tropical country, I thought I’d learned about seasons from my few years in the UK. But the persimmon tree showed me how little I understood. I’d never taken the time to observe how plants morph and shift over a year, how they can take on a dozen different faces and still delight you week after week. Spring begins with bright yellow-green leaves that darken as summer approaches and fruit forms. Autumn breathes shades of fire, rust, bronze into the leaves, which blanket the ground as the cold creeps in. Persimmons tend to remain long after the leaves have fallen, slender branches weighed down by clusters of fruit slowly rotting and shrivelling out of reach. You leave some behind for the birds, 木守り kimamori, as a way of ensuring good harvests and fortunes for the coming year. And winter, eventually, outlines its skeleton in inches of settled snow. So the cycle goes.

■ ■

How do you describe something you’ve never eaten before? I had no frame of reference for this fruit. A just-ripe persimmon off our tree was sweet, crisp, honey-like. When its flesh ripened even further, becoming soft and pulpy, it tasted like an autumn mango, hints of toasted brown sugar and dates and a dash of cinnamon. It tasted like the sound of a clarinet – silky, mellow and warm. I assumed all persimmons could be eaten straight off the tree. I didn’t know that hundreds of varieties existed, or that they fell broadly into astringent and non-astringent types. Later, I found out the hard way that an under-ripe astringent persimmon tastes like a thousand green bananas, and turns your tongue into a shag rug for half an hour.

It was the first time I had lived up close with an actual fruit tree. The autumn bounty felt miraculous and impossible, these mounds of beautiful imperfect fruits with their bruises and webs of blemishes, so different from perfectly square supermarket persimmons suffocating in their plastic prisons. Without any effort the tree simply grew, year after year, a gift unasked for. It felt a bit like my life: a job, a friend, a tree, a roof over my head, all of these things I hadn’t asked for but had received like a benediction. It took years to stop feeling guilty for all this good fortune.

■ ■

Things I’ve told myself over the years: She must have had her reasons. She may have outgrown you. You weren’t compatible with who she was becoming. You were a lot to handle as a friend. Okay, you kind of sucked. You never felt things by halves, and neither did she. She may have seen this as a toxic relationship. Her feelings are valid and so are yours. You have become different people. It’s okay to miss someone who isn’t in your life anymore.

■ ■

Life in the house revolved around the kitchen, where we answered emails and took phone calls across from each other at a rickety white IKEA table. In the kitchen we worked, cooked, listened to music, and got to know each other better. I wasn’t accustomed to sharing space so closely with someone who wasn’t family or, indeed, to tending to the logistics of a shared household, and I suspect she would have lived by herself if the rent had been tenable on our low salaries. In retrospect,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.2.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | The Emma Press Prose Pamphlets |

| The Emma Press Prose Pamphlets | The Emma Press Prose Pamphlets |

| Mitarbeit |

Cover Design: Elīna Brasliņa |

| Verlagsort | Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | essay collection • Essays • Friendship • intense friendship • Japan • Kyoto • Memoirs • Travel writing |

| ISBN-10 | 1-915628-01-6 / 1915628016 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-915628-01-5 / 9781915628015 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich