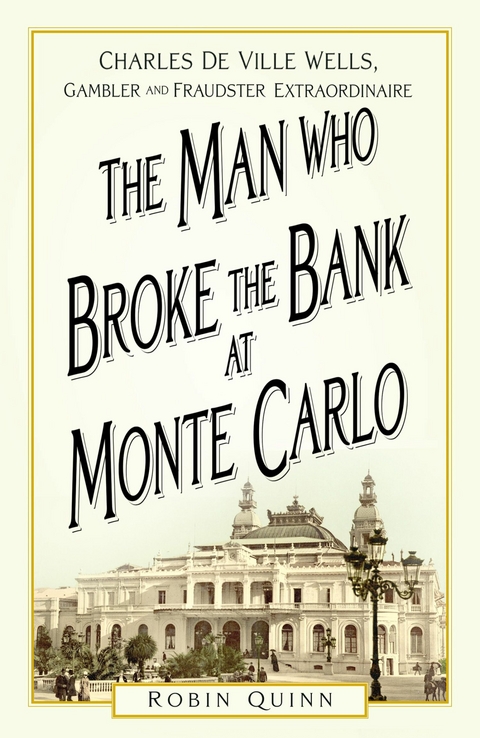

Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo (eBook)

368 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-6926-0 (ISBN)

ROBIN QUINN is an author and independent radio producer based in South-East England. His first book, Hitler's Last Army (THP), is the story of the 400,000 German prisoners of war detained in Britain during and after the Second World War. He contributes to family history and other magazines, and has written and produced over sixty programmes for BBC network radio, including the critically acclaimed Summer of 1940 and The Cuban Crisis (Radio 2).

THE INCREDIBLE TRUE STORY OF THE MAN WHO BROKE THE BANK AT MONTE CARLO. 'Brilliant a terrific read' - Michael Aspel OBE'The best book I've read all year' - Nigel Jones, editor, Devonshire MagazineCharles Deville Wells broke the bank at Monte Carlo not once but ten times winning the equivalent of millions in today's money. He followed up with a colossal bank fraud in Paris, and became Europe's most wanted criminal, hunted by British and French police and known in the press as 'Monte Carlo Wells the man with 36 aliases'. Is he phenomenally lucky? Has he really invented an 'infallible' gambling system, as he claims? Or is he just an exceptionally clever fraudster?

1

A Frenchman in the Making

The man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo – Charles De Ville Wells – was born at Broxbourne in the county of Hertfordshire, England, on 20 April 1841. It was not until 28 May that Charles’ father finally got around to completing the formality of registering the birth. Charles Wells senior was a man who found it difficult to get around to doing anything much, except hunting, shooting, boating, catching fish and keeping bees. And he only kept bees because, as one of his friends claimed, ‘while the bees were working he could be fishing’.

Charles’ father – his full name was Charles Jeremiah Wells – was born in London in January 1799, the son of a well-to-do merchant. He grew into a striking young man with ‘sparkling blue eyes, red curls, and bluff, rather blowsy complexion … a bright, quick, most piquant lad, overflowing with wit and humour’.

At school, he made friends with another pupil, John Keats, who was destined to become one of the most illustrious of all English poets. Wells had literary ambitions of his own and the two young men talked incessantly about writing and poetry. Wells once sent some flowers to Keats, who responded by dedicating a sonnet to Wells:

But when, O Wells! thy roses came to me

My sense with their deliciousness was spell’d:

Soft voices had they, that with tender plea

Whisper’d of peace, and truth, and friendliness unquell’d.

As a young adult, Charles Jeremiah Wells gained a reputation as an ebullient, noisy extrovert, whose high spirits sometimes got the better of his judgement. When he was about 20, he played a mischievous trick on John Keats’ younger brother, Tom. He faked a series of love letters from an imaginary girl who is supposed to have fallen for Tom. The prank backfired. Tom’s disappointment on finding that there was, in fact, no female admirer upset him considerably. And there was a complication – Tom had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and died soon afterwards. John Keats placed the entire blame for his brother’s death on Wells.

‘That degraded Wells,’ he wrote. ‘I do not think death too bad for the villain … I will harm him all I possibly can.’ In an attempt to regain John’s trust, Wells wrote an epic poem, Joseph and his Brethren. It is similar in style to Keats’ own writing, and perhaps Wells had intended to flatter his friend. ‘I wrote it in six weeks to compel Keats to esteem me and admit my power,’ he later wrote, ‘for we had quarrelled, and everybody who knew him must feel I was in fault.’ In fact, it seems that John Keats never spoke to him or even referred to him ever again.

Although Charles Jeremiah Wells was set on pursuing a literary career, his parents forced him against his will to train as a lawyer. But he found the work dull and unsuited to his adventurous spirit. By day he worked with covenants, conveyances, deeds and affidavits; by night he caroused with new-found literary friends, who included the poet William Hazlitt. The pair ‘used to get very drunk together’ every night.

Around 1823–24 Wells decided to publish Joseph and his Brethren. But the book-buying public ignored it completely. It was a rejection that Wells never really recovered from.

In 1825, he married Emily Jane Hill, the daughter of a teacher who ran a ‘boarding and day school’ at Broxbourne. No description of her seems to have survived, but a letter that she wrote in later life displays – as we might expect of a teacher’s daughter – beautifully formed handwriting (in contrast with her husband’s spidery scrawl) with equally pristine spelling and grammar. The overall impression we gain is of a pleasant, mild-mannered, and self-effacing woman, perhaps inclined to be a little fussy and preoccupied with detail, accuracy and correctness.

Or to put it another way, she and her husband were two very different individuals. Charles was creative, lackadaisical, unscrupulous, extroverted and sometimes overbearing. Emily, on the other hand, favoured order and neatness, and made her way through life with patience and a quiet, yet strong, determination.

And, as we shall see, their son would inherit a curious mixture of these traits.

By 1831, Charles Jeremiah Wells had given up his legal practice. Around 1835 the couple relocated to Emily’s home village of Broxbourne, which then had a population of about 550. They moved into an impressive house on the main street. (Plate 11)

An inheritance from his father allowed Charles to indulge his passion for outdoor activities, to which he now devoted most of his time. As well as shooting, fishing and beekeeping, he turned his hand to horticulture. According to his wife, he ‘would have been a really good gardener but for his impatient habit of now and then pulling up plants to see how the roots were getting on, carefully putting them back again. He would do this early in the morning, before anybody else was up.’

The couple had three daughters: Emily Jane (named after her mother), Anna Maria and Florence. (Another girl and a boy were also born, but died in infancy.) So now all that was missing from their lives was a son. Every nineteenth-century family yearned for a male heir and they must have longed to fill the void left by the death of their first son. Charles Jeremiah Wells was, by now, around 40 years of age and Emily was in her mid-thirties. It was by no means too late for them to have a son, but perhaps they were beginning to sense that time was moving on.

The birth of Charles Wells in the spring of 1841 put an end to these concerns. They gave him the unusual middle name of De Ville, probably in honour of one of Charles Jeremiah’s friends – a man named James Deville who lived on the same street. Both men had connections with the parish church in the village: Wells was one of the overseers of the poor, while James Deville served as a church warden.

On 30 May, the infant Charles, and his sister, Florence, who was now nearly 4, were christened in a joint ceremony by the Reverend Francis Thackeray (who happened to be the uncle of the author William Makepeace Thackeray). Shortly afterwards, 6-week-old Charles and the rest of the family were officially recorded in Britain’s first census. This shows that Emily’s brother, Robert Hill, and his family were living at the same address, and the household includes either three or four servants.

Broxbourne would have been a splendid place for young Charles to grow up, but a few weeks after he was born, the family moved out of their home and auctioned off many of their most valuable possessions. A partial list of the goods they sold gives some impression of their comfortable lifestyle up to that point: a pianoforte by Robert Wornum, the eminent maker of musical instruments, together with two other pianos; a phaeton coach with a ‘handsome black pony’ and harness; bees, and a beehive; a four-poster bed; other beds and bedding, furniture, carpets, ‘kitchen and culinary articles … and many other valuable effects’.

What we see here are the trappings of a wealthy family being turned into ready cash. It is unclear whether they had run short of money, or whether there was some other compelling reason to move away from the area. Charles Jeremiah Wells – although he apparently did no work – had managed to live the life of a wealthy country squire, surrounded by luxury goods which most of the villagers could never dream of owning. But after giving up this carefree existence, the family – including Emily’s brother, Robert, and his wife, Mary Anne – crossed the Channel to begin a new life in France, the country where young Charles would spend most of his life.

The French département of Finistère – (literally, Land’s End) – lies in the extreme north-west corner of France, in Brittany, nearer to the south-west coast of England than to Paris. The people’s roots are remote from the rest of France, too. The railway had not yet reached these parts and communications with other parts of the country were extremely difficult. It comes as no surprise then that this isolated region had developed its own culture. The Breton language – widely spoken when the Wells family arrived in the mid-nineteenth century – has direct links to the Cornish tongue. And locally the region is known as Cornouailles – a name sharing the same origin as Cornwall.

The landscape is rugged, with rough, jagged summits and abrupt changes of gradient and elevation. The slopes are wild and featureless, often bare but sometimes dotted with heather. In winter storms batter the coast, and even in summer the weather can be capricious.

The region being so remote and lacking in the comforts that the Wells family had grown accustomed to, it is hard to fathom quite why they chose to move here in the first place. But Charles Jeremiah Wells and his extended family settled in the town of Quimper (pronounced ‘camp-air’), the principal town of the region. What they found here was an ancient community with many mediaeval buildings, where the streets had curious names, such as Rue du Chapeau Rouge (Red Hat Street) and Ruelle du Pain Cuit (Baked Bread Alley). The River Odet flows through Quimper, and although the town is some 9 miles inland, it had a thriving fishing port based on the quay near the town centre.

By any measure, with its 10,000 inhabitants, Quimper was small. Only about 100 of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.8.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Spielen / Raten | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Politik / Gesellschaft | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| Schlagworte | Biography • british police • Charles deville wells gambler & fraudster extraordinaire • Charles deville wells gambler and fraudster extraordinaire • Charles deville wells gambler and fraudster extraordinaire, Charles deville wells gambler & fraudster extraordinaire, true story, French mistress, Jeannette, yacht, palais royal, roulette table, monte carlo casino, gambling, fraud, fraudster, Monaco, French police, british police, biography, • Fraud • fraudster • French mistress • french police • Gambling • Jeannette • Monaco • monte carlo casino • monte carlo wells the man with 36 aliases • |most wanted criminal • most wanted criminal, monte carlo wells the man with 36 aliases, true crime, real crime, • Palais Royal • Real Crime • roulette table • True Crime • True story • Yacht |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-6926-1 / 0750969261 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-6926-0 / 9780750969260 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich