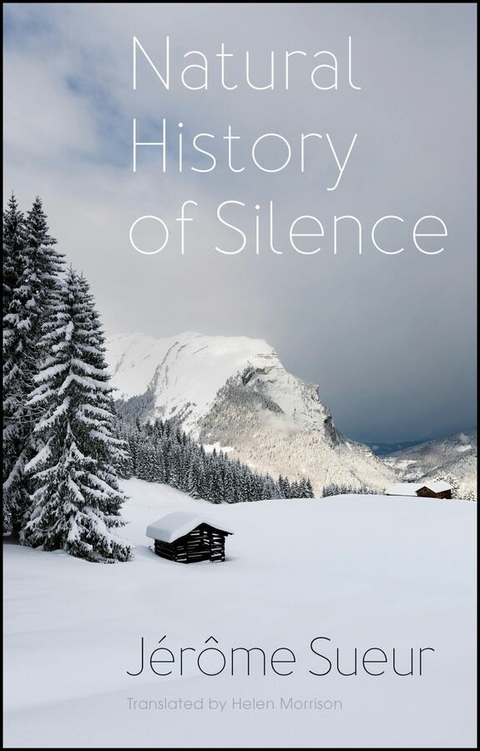

Natural History of Silence (eBook)

249 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6403-3 (ISBN)

In our busy, noisy world, we may find ourselves longing for silence. But what is silence exactly? Is it the total absence of sound? Or is it the absence of the sound created by humans - the kind of deep stillness you might experience in a remote mountain landscape covered in snow, far away from the bustle of human life?

When we listen closely, silence reveals a neglected reality. Neither empty nor singular, silence is instead plentiful and multiple. In this book, eco-acoustic historian Jérôme Sueur allows us to discover a vast landscape of silences which trigger the full gamut of our emotions: anxiety, awe and peace. He takes us from vistas resplendent with full and rich natural silences to the everyday silence of predators as they stalk their prey. To explore silences in animal behaviour and ecology is to discover a counterpoint to the acoustic diversity of the natural world, throwing into sharp relief the grating reverberations of the human activity which threatens it. It is to attune ourselves to a world that our human insensitivities have closed off to us, to take a moment simply to breathe and listen to the place of silence in nature.

Jérôme Sueur is an associate professor at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris where he is director of the eco-acoustic laboratory.

2

The essence of sound

In the space of just a short walk in my snowshoes, I had experienced the deep silence of a snowbound mountain landscape. Was this therefore what silence meant? A moment of solitude and of peace in a natural environment encased in ice and cold? Was silence an acoustic stillness where only a few flakes of sound still drifted past – a rustling of feathers, the slither of snow falling from branches? Was silence an absence of sounds and, as a result, a lack of information emanating from the surrounding landscape?

Yet, if this is indeed the case, how can we set about identifying an absence, a sort of emptiness? How can we define this antimatter, silence, without turning our attention to matter, in the form of sound? In order to understand silence, we must necessarily be familiar with sound. Who or what exactly is sound? What is this quivering yet formless creature which constantly makes its presence felt, even as we sleep, in the circumvolutions of our outer ears, tapping softly against our eardrums, gently stirring the stapes, the malleus and the incus in our inner ears, circling through the spirals of our cochlea, travelling along our nerves like a train advancing on its tracks, and finally awakening the neurones in our brains?

According to the laws of physics, sound is a modification of the pressure or density of a gas, fluid or solid caused by the endogenous or exogenous vibration of an object. Regardless of what that object is – a piano, a toaster, a copper beech or a whale – sound travels through air, water, vegetable or mineral matter. Without its medium, sound is nothing. In fact, sound is an integral part of the medium through which it is propagated: sound is air, water, plant or pebble and has been there since gases, liquids or solids first existed on earth. If sound fades with distance, bounces back and is diffracted by obstacles, it can also pass from one medium to another, from air to water, from water to rock, from rock to plants and from plants to air. Sound knows no frontiers; it disperses, permeates and then spreads out in all directions. All routes are possible as long as sound retains sufficient energy and the matter it travels through is capable of distortion.

Today, as I write, everything around me is vibrating in an atmosphere of hypersensitivity; the blue tit on the cherry tree in the garden, the radio in the kitchen, the neighbour’s cat. Far away from me, sound is also vibrating. At exactly the same moment, sound is travelling to and fro in the humidity of tropical forests, in the frozen wastes of taigas, in the arid expanses of deserts. It plunges into the water of streams, lakes, rivers, ponds, seas and oceans, it passes through flowers, shoots, buds, fruit, leaves, trunks and branches and it travels through rocky ground, across sandy beaches and deep into the earth’s crust.

Omnipresent outside, sound also rumbles continuously inside us. It enters through our ears and does not re-emerge, it travels effortlessly through our bodies, it reaches our organs, touches our unborn children. Our bodies are themselves a source of sound, pulsing constantly with the beating of our hearts, grinding in our sleep, creaking as our joints stretch and gurgling with gastric rumblings when we are seized by hunger.

At each moment, day and night, we are therefore both the target and the source of these sound arrows. All we need to do in order to tune into this omnipresent sound is to close our eyes, concentrate for a few seconds, and analyse the acoustic landscape that is playing out all around us. Voices, music, bodies, plants, winds, rains, storms and objects send or re-send the sounds which continuously bombard all of us, all the time, and which rarely come in isolation but are often mixed with others.

Sound is an essential element of our lives both inside and outside the womb, and a key to our survival. Sound in the form of the spoken word is the fundamental basis of our family and social relationships and keeps us constantly informed about the state of our environment and any changes to it. The framework of an immense network which connects and informs living creatures, sound is also a source of distraction, of relaxation. It alerts us, stimulates us and sometimes controls or irritates us. Sound penetrates our bodies for better as well as for worse.

In the air, sound is the relatively regular and relatively complex alternation of the longitudinal compressions and dilations of atmospheric particles. These particles oscillate around their position, never moving much further away than a few dozen nanometres. This small and very precise movement gives rise to an important phenomenon: the nano-oscillations of particles are transmitted from one to another in such a way that the alternating compression-dilation is capable of being transmitted over long distances, sometimes as much as several kilometres. The movements of the particles are small and weak, but the sound wave is big and powerful and the differences in pressure which occur can have a dramatic effect on us. How strange that we are incapable of seeing sound even though it is sometimes so intense as to be painful. In order to do that, we are obliged to resort to a little help from sensitive receptors in the form of microphones, accelerometers, laser vibrometers and mathematical manipulations capable of converting sound into image.

The physical description of a sound wave is made up of four main dimensions: amplitude, duration, frequency and phase. Amplitude is the strength, pressure, energy, power and intensity of the sound. All these terms from mechanical physics are linked to each other by variables of acceleration, mass, surface, density, celerity, impedance and time. Beyond the underlying mathematics, which are in fact relatively straightforward, it is simply a matter of remembering that the greater the amplitude of a sound, the more that sound distorts its medium of transport. The trumpeting of an African elephant displaces air particles to a greater extent than do the wingbeats of the mosquito buzzing around its ears.

The second dimension, a purely temporal one, is easier to grasp. A sound is not an indefinite event. It has a beginning and an end, a duration. While each sound contains its own history, made up of complex events of transduction, diffusion, dispersal, propagation, refraction, reflection and diffraction, sound is essentially transient, an event of the moment. The birth of a sound is relatively easy to determine given that it corresponds to the beginning of the vibration which occurs when the particles of the medium pass from a state of rest to a state of activity. This process is usually a rapid one, marked by a clear increase in amplitude. The death of a sound, on the other hand, is more difficult to pin down. Sound can often take a certain time to fade completely. The length of time required for a sound to die depends first of all on the physical absorption properties of its source and, in particular, its mass and elasticity. A resonating object such as a church bell takes longer to stop vibrating than a sound which is more spontaneously produced, like the snapping of fingers. The duration of a sound also, and even more importantly, depends on the inherent physical properties of the medium, such as its volumetric mass and impedance, and the extent to which the physical space is encumbered by the presence of other objects which can reflect the sound, creating echoes, or, on the contrary, absorbing and stopping it.

Subtle, discreet, hidden behind the broad shield of temporal variations and amplitude, phase nevertheless plays an essential role in the production, propagation and reception of sound. Phase is a temporal property which is a little more difficult to grasp since it is expressed in an unfamiliar unit, the radian, and with the golden number of π. Phase is used to define periodic sounds, or in other words, sounds which have repeated or cyclical time patterns. It is a way of describing position and indicates the location of the wave within the wave cycle which is circular in form.

Finally, frequency, perhaps the best-known aspect of sound, corresponds to the number of cycles travelled by a sound wave in a second, a number expressed in hertz (Hz). The greater the number of cycles, the higher the sound, and conversely. The sounds which surround us are very rarely made up of a single frequency but are more often a whole range of sounds covering a wide spectrum of frequencies, ranging from low frequencies of just a few hertz to very high frequencies measuring several thousand hertz. Sounds inaudible to humans are referred to as infrasounds when frequencies are lower than 20 hertz and as ultrasounds when they are in excess of 20,000 hertz.

Since a musical metaphor is unavoidable when it comes to describing sound, it is possible to see amplitude in terms of nuances such as pianissimo, forte, fortissimo, duration in the form of notes, quavers, quarter notes, whole notes, and frequency in terms of pitch – C, D, E. Only phase, eternally forgotten, does not seem to have any equivalent in the western system of musical notation, even if it is an important factor in the craftsmanship of instruments and in the engineering behind sound recording and reproduction.

Amplitude, duration, frequency and phase are not independent properties – amplitude is measured in a predefined temporal window, frequency is the opposite of a temporal period, duration is a specific time, and phase is a characteristic of both amplitude and time. Time is therefore the fundamental dimension of sound.

Hearing means...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Helen Morrison |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz |

| Schlagworte | ability to hear • absence of sound • animal behaviour • Anthropocentrism • Birdsong • Body Percussion • can we communicate better with animals • can we read other minds • chirping • city-dweller • Deafness • eco-acoustic • Ecology • Environment • five senses • Forest • Frequency • geophysical warning signs • how can we understand how animals think and feel • how do we co-exist with animals • how is sound linked to survival • Human activity • Isolation • is true silence possible • Jérôme Sueur • listening • musical signals • Natural History of Silence • Nature-human Dualism • Noise • remote mountain landscape • Rural • Sense • sensibility • Silence • sound habitat • Sounds • Soundscape • Stridulation • Urban • urban sprawl • Voice • what does the world sound like without humans? • what do frogs hear • what is silence |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6403-9 / 1509564039 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6403-3 / 9781509564033 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 326 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich