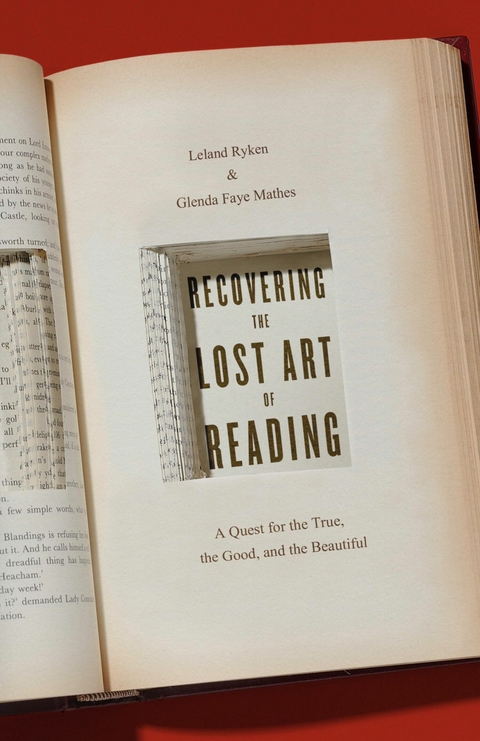

Recovering the Lost Art of Reading (eBook)

304 Seiten

Crossway (Verlag)

978-1-4335-6430-7 (ISBN)

Leland Ryken (PhD, University of Oregon) served as professor of English at Wheaton College for nearly fifty years. He served as literary stylist for the English Standard Version Bible and has authored or edited over sixty books, including The Word of God in English and A Complete Handbook of Literary Forms in the Bible.

Leland Ryken (PhD, University of Oregon) served as professor of English at Wheaton College for nearly fifty years. He served as literary stylist for the English Standard Version Bible and has authored or edited over sixty books, including The Word of God in English and A Complete Handbook of Literary Forms in the Bible. Glenda Faye Mathes (BLS, University of Iowa) is a professional writer with a passion for literary excellence. She has authored over a thousand articles and several nonfiction books as well as the Matthew in the Middle fiction series. Glenda has been the featured speaker at women's conferences and at seminars for prison inmates.

1

“Read any good books lately?”

This question once functioned as a common conversation-starter, but now we’re more likely to hear, “What are your plans for the weekend?” or “Did you catch the game last night?” There’s nothing wrong with spending time with family and friends on weekends or cheering on favorite sports teams. But could the prevalence of such questions indicate that these activities are eclipsing thoughtful conversations about reading?

The question about reading good books may seem blasé or even a cliché. But it’s still used to launch literary discussions, and it effectively reflects this chapter’s focus.

The negative connotations surrounding this question could be rooted in the phrase’s history. It began initiating conversations almost a century ago, during the Roaring Twenties. BBC radio personality Richard Murdoch popularized it with a humorous twist in the 1940s, when he interjected it into dialogue as a comic attempt to change an unwelcome subject. Amusing variations came into play during ensuing years, and the catch phrase lost validity as a serious conversation starter.1 Despite existing negative perceptions, it continues to enjoy a measure of popularity. Bloggers sometimes ask the question to head posts about books they recommend. Prominent Christians Stephen Nichols and Sinclair Ferguson have employed it respectively for a church history podcast and as a book title.2

Maybe “Read any good books lately?” is making a serious comeback. It could be a legitimate way of jumpstarting more conversations. We’re using it here because it encompasses much of this chapter’s scope. Each word packs a specific punch.

Read = This chapter reflects this book’s focus on reading.

Any = Research shows that many people don’t read any books or can’t name a single author.

Good = This chapter’s discussion touches on the concepts of literary quality and reading competency.

Books = Reading on screens differs from reading physical books.

Lately = We’re addressing the current situation by providing recent information and statistics.

You may recognize these elements as we explore this chapter’s primary question: Is reading lost?

The Current State of Reading

Most adults have 24-hour access to a constant stream of information. You may peruse a physical newspaper while sipping your morning cup of coffee, but you’re more likely to respond to emails, scroll your Facebook feed, or skim top news stories on your phone. The screen-reader could be scanning more words than the person reading the paper. With the incredible volume and easy accessibility of information today, aren’t people reading more than ever?

Yes and no. Many people are reading a great deal of material, especially online. But they are not necessarily reading quality material or reading well.

Surveys consistently show that most people believe reading is a worthwhile use of time and they should do more of it. But some people don’t read any books. Gene Edward Veith Jr. writes: “A growing problem is illiteracy—many people do not know how to read. A more severe problem, though, is ‘aliteracy’—a vast number of people know how to read but never do it.”3 Most of us could (and suspect we should) read more and read better.

Our worm of suspicion may even evolve into a dragon of guilt. Or we may think of reading as a duty we’re neglecting, while feeling overwhelmed at the very idea of crowding one more thing into our busy lives. In this book, we aim to alleviate any reading guilt or anxiety. We want you, whether you read a little or a lot, to experience more joy in reading (and therefore in life). We want to dispel the notion of reading as duty and instill the concept of reading as delight.

Perhaps reading had declined in recent decades, but isn’t it increasing now? The 2009 report by the National Endowment for the Arts, Reading on the Rise, celebrated (according to its subtitle) “a new chapter in American literacy.” The NEA might well rejoice in any increase over the statistics reflected in its pessimistic 2004 report, Reading at Risk, which bemoaned previous decades of decline.4 While Americans can join in the NEA’s joy, we should pause for further consideration before patting ourselves on the back.

The Pew Charitable Foundation reported in 2018 that nearly a quarter of American adults had not read a book in any form within the past year.5 This figure painted a slightly brighter picture than the high of 27 percent non-book readers in 2015. Still, it’s a sobering statistic. Think of the people walking our city streets. Out of every four adults, one has not cracked open a physical book, downloaded a digital copy onto a device, or even listened to an audiobook.

British research expands our understanding of current reading culture. A recent statistic from the Royal Society of Literature sounds similar to the Pew report’s finding. The 2017 RSL report showed that one out of five people could not name an author—any author.

On the positive side, the report showed people have a keen desire to read more literature. Nearly all respondents believed everyone should read literature, which they viewed as not limited to classics or academics. Over a third of those who already read want to read more in the future, while over half of those who currently do not read literature expressed a desire to do so. But many of those surveyed find literature—even material not considered classic or academic—difficult to read.6

The amount of time Americans spend reading each day increases with age, with retirees reading the most. But even those in the seventy-five and above age bracket read only 50 minutes per day. Not a single age group averages as much as an hour of daily reading.7

Compare that with the time people spend on digital media, which according to one study averages a whopping 5.9 hours per day. This nearly six hours per day may not be so surprising when you consider it includes smartphones, computers, game consoles, and other devices for streaming information.8 Pew Research indicates about three-fourths of Americans go online daily. More than a quarter of US residents admit to being online “almost constantly.”9 No wonder many people express concern about society’s burgeoning information technology and its possible relation to recent reading trends.

Finding Peace in a Reading War

Research on reading reveals a fascinating recurrence of references to Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Why are so many people writing about a Russian novel published more than a hundred and fifty years ago? Probably because War and Peace is often regarded as a litmus test for reading ability and perseverance.

Professor Margaret Anne Doody explains: “War and Peace is one of those few texts . . . too often read as some kind of endurance test or rite of passage, only to be either abandoned halfway or displayed as a shelf-bound trophy, never to be touched again. It is indeed very long, but it is a novel that abundantly repays close attention and re-reading.”10

Careful attention appears to be a vanishing reading skill in our busy, technology-glutted lives. Writer Nicholas Carr famously asked, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” While he noted the benefits of online research and accessible information, Carr found that he and many others struggle to read as well as they formerly did. One of his friends can no longer read War and Peace because scanning short online texts has given him a “staccato” thinking quality.11

In response to Carr’s article, writer and speaker Clay Shirky celebrated the demise of literary reading and its culture. He wrote, “But here’s the thing: it’s not just Carr’s friend, and it’s not just because of the web—no one reads War and Peace. It’s too long, and not so interesting.”12 Quite the blanket statement, but is it valid?

Professor Alan Jacobs sarcastically assessed Shirky’s statement by noting how the “reading public has chosen to pronounce this devastating verdict against Tolstoy’s masterpiece by purchasing over one hundred thousand copies” of War and Peace in the past four years, which he observes is “an odd way of making its disparagement known.”13 Any modern writer with that many copies sold in four years would be making the talk show rounds and juggling offers from major publishers.

At 560,000 words, there’s no denying War and Peace is a hefty read. But several other novels—including Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.3.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Wheaton |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Biblical Studies • Reformed • seminary student • Systematic • Theological • Theology |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4335-6430-0 / 1433564300 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4335-6430-7 / 9781433564307 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 630 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich