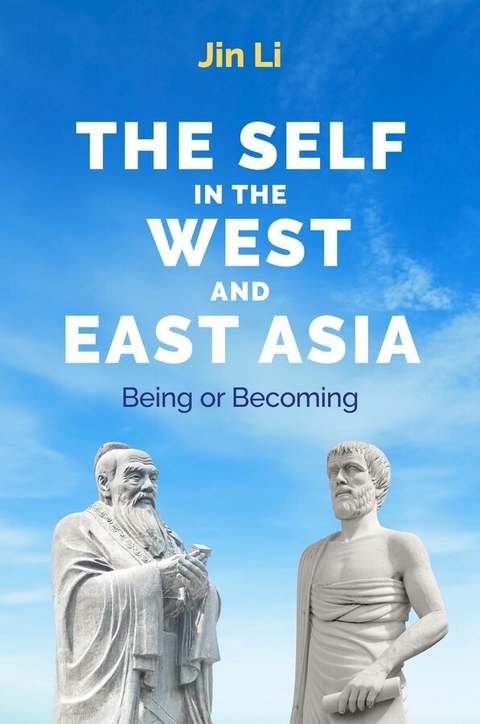

The Self in the West and East Asia (eBook)

611 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6137-7 (ISBN)

From the fraught world of geopolitics to business and the academy, it's more vital than ever that Westerners and East Asians understand how each other thinks. As Jin Li shows in this groundbreaking work, the differences run deep. Li explores the philosophical origins of the concept of self in both cultures and synthesizes her findings with cutting-edge psychological research to reveal a fundamental contrast.

Westerners tend to think of the self as being, as a stable entity fixed in time and place. East Asians think of the self as relational and embedded in a process of becoming. The differences show in our intellectual traditions, our vocabulary, and our grammar. They are even apparent in our politics: the West is more interested in individual rights and East Asians in collective wellbeing. Deepening global exchanges may lead to some blurring and even integration of these cultural tendencies, but research suggests that the basic self-models, rooted in long-standing philosophies, are likely to endure.

The Self in the West and East Asia is an enriching and enlightening account of a crucial subject at a time when relations between East and West have moved center-stage in international affairs.

Jin Li is Professor of Education and Human Development at Brown University. Originally from China, she studied German literature and language before moving to the United States, where she has lived since the late 1980s. Her research focuses on East Asian virtue-oriented and Western mind-oriented learning models and how these shape children's learning beliefs, parental socialization, and achievement. She is the author of Cultural Foundations of Learning: East and West (2012).

From the fraught world of geopolitics to business and the academy, it s more vital than ever that Westerners and East Asians understand how each other thinks. As Jin Li shows in this groundbreaking work, the differences run deep. Li explores the philosophical origins of the concept of self in both cultures and synthesizes her findings with cutting-edge psychological research to reveal a fundamental contrast. Westerners tend to think of the self as being, as a stable entity fixed in time and place. East Asians think of the self as relational and embedded in a process of becoming. The differences show in our intellectual traditions, our vocabulary, and our grammar. They are even apparent in our politics: the West is more interested in individual rights and East Asians in collective wellbeing. Deepening global exchanges may lead to some blurring and even integration of these cultural tendencies, but research suggests that the basic self-models, rooted in long-standing philosophies, are likely to endure. The Self in the West and East Asia is an enriching and enlightening account of a crucial subject at a time when relations between East and West have moved center-stage in international affairs.

1

TO BE OR NOT TO BE: THAT IS A STRANGE QUESTION

China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–76) was, as officially condemned, a self-inflicted political, social, cultural “calamity of 10 years” (十年浩劫), not just to the country but to virtually every individual. Like millions of unlucky young children, the ten years of revolution that I endured were from age ten to age twenty, a period of human development treasured as golden and irreplaceable. But there was light at the end of the tunnel. Although still hopelessly stuck in the countryside to continue our re-education – as dictated by Mao Zedong’s grand design to yank out our bourgeois book knowledge so as to shovel into us “real” knowledge from farming labor1 – the mass of “re-educated youth” was allowed to take the first college entrance examination (known as gaokao since), thanks to China’s new leadership. Like buying a lottery ticket, the odds were unnervingly slim.2 But in the end, I actually passed. Elatedly, I enrolled in college. No doubt, that was what the Chinese would call heavenly luck. Indeed, it felt like being liberated from hell and ascending to heaven.

I was placed to study German.3 I hadn’t the faintest idea of what that language was about. But I knew that it was a Western language of importance, as we were told, because it was Marx’s native tongue, so I’d better learn it well! Feeling extremely blessed, I began learning this European language. It was such an eye-opening and life-altering experience that I have come to call it “my gaze and gate into the West.”

That’s right: in my humble understanding now (but not then), one’s first encounter with a foreign culture is through its language. Then, if one survives that encounter and doesn’t abandon one’s exploration, the initial glance becomes a gaze, and eventually an entrée into that culture. A language embeds and weaves into its cultural fabric not just the obvious tangible things in its milieu, but the intangible, the more fundamental, as the particular construal of their world. Even Nietzsche, the Western philosophical rebel, remarked:

The strange family resemblance of all Indian, Greek, and German philosophizing is explained easily enough. Where there is an affinity of languages, it cannot fail, owing to the common philosophy of grammar – I mean owing to the unconscious domination and guidance by similar grammatical functions – that everything is prepared at the outset for a similar development and sequence of philosophical systems; just as the way seems barred against certain other possibilities of world-interpretation.4

In other words, different human languages reveal different philosophical outlooks of their cultures.

Bewilderment of German

German is a tough language, even for non-Germanic Westerners. I do not know how other European native speakers deal with German, but native English speakers generally find German grammar, particularly the four cases along with their endless conjugational and combinatorial variations, cumbersome if not mentally torturous. For us, it felt like trying to get through a brick wall. Chinese, regardless of dialect, is spared all the linguistic morphology. I remember once saying to myself: “Had I known what Marx’s native tongue entailed, I would have not so heartily embraced it.” However, we had no choice but to forge ahead. Facing this daunting learning task, we, the toughened but lucky Chinese students emerging from the revolutionary crucible, did not back down but buckled down. We managed to absorb all the hard complexities through endless drilling until we could get the forms right.

But then we encountered a stumbling block: the verb sein. This verb is similar to the English infinitive to be. To Western language speakers, this verb is as common as eye-blinking. We learned that one cannot make any sentence in any Western language without inserting a verb, by formal linguistic definition, not communication with loose omissions but buttressed by contextual clues. Even when there is no real need for the verb’s meaning, speakers still must use a verb (as a filler). But Chinese has none of this. For example, in Chinese we say “我很高興” – literally “I very happy” – but in English the correct way to say this is “I am happy” (i.e., by inserting the verb am), or “Ich bin sehr glücklich” in German.

The conjugated forms of sein, ich bin (er ist, sie ist, wir sind …) or I am (he is, she is, we are …) in English are necessary to construct “ich bin sehr glücklich” or “I am very happy.” So sein/be is just simple everyday speaking in the Western world. It is so basic that hardly anyone would think twice about it until we (from a different world) had to learn how to speak it, trying to do surgery to our minds that were accustomed to “I very happy.” To the Chinese mind, all this need for a verb is utterly unnecessary. “Ich sehr glücklich” and “I very happy” would suffice and is economical.

In our struggles to understand sein, we hit a bigger roadblock, and this time it was philosophical. The verb sein is now turned into a noun, so Sein.5 As if this was not enough, every German noun denoting things tangible or intangible has one of the three definite articles, unlike the much simpler the in English: das, der, die denoting neutral, masculine, and feminine, respectively. And these are more or less arbitrarily assigned, thus requiring learning by rote. Any verb turned into a noun automatically gets the neutral article das. So das Sein. Think about it. If our minds could be retrained to use the filler verb sein, what the heck is das Sein?

In hindsight, I must marvel at German ancestors for first coming up with such purely abstract ideas. Even more remarkable is the fact that they succeeded in injecting these ideas into their language and managed to make that a part of everyone’s language instinct.6 I am stunned!

What is das Sein? According to Saussure’s linguistic theory,7 even if a noun does not have a referent (usually a tangible thing, e.g., table), it is still a sign, a “signifier” denoting a concept or an idea, called “the signified.” What does das Sein signify that we ought to be able to sense if not see and imagine? When we first encountered this linguistic transformation, we were baffled. At that time, my peers and I could not understand why the Germans feel a need to use this strange word. The “signified” felt hollow. But why would the Germans do that routinely with their verbs? It seems that the more abstract a given verb is, the more often it is turned into a noun, as if they are in love with playing empty linguistic games!

Lost in an English fog of to be

As we lost our way in the fog (如墜五裏雲霧), things got worse. Our fellow English peers were stumbling over similar things, although they were perhaps in less agony. One morning, as I was doing my reading-aloud routine,8 I passed by an English student who was reciting aloud the famous Shakespearean line in Hamlet’s soliloquy: “To be or not to be, that is the question.” I paused to try to process what I had just heard. I thought the student was speaking gibberish, because he was reciting this phrase again and again trying to make it sound right. I remember thinking to myself, “What kind a question is that? THE question? How come there is no subject, who is to be or not to be? To be or not to be with whom, where, doing what? How strange to pose this incomplete thought as a question to oneself or anyone else!” Endless questions swarmed through my brain.

I became curious about how this famous Shakespearean phrase/question has been translated into Chinese. I found some twenty translations of Hamlet, with that by Zhilin Bian (卞之琳) regarded as the best. These bilingual literary figures translated the phrase, with a few variations, as: “To exist after death or not to exist”; “To exist or to be destroyed”; and “To continue to live or not to live.”9

I do not need to convince English readers familiar with Shakespeare that none of these translations captures the English phrase made up simply by the verb to be and its negation. These sophisticated and highly esteemed translators were faced with an impossible task: they could not really find the linguistic match of the full meaning of the original terse phrase. There is no choice but to make it much less abstract, or, shall we say, much more ontologically particular. They had to do what good literature rarely does: to concretize, namely, to unpack, the expression for their Chinese readers. At least this would allow them a chance to comprehend some meaning of Hamlet’s utterance. It was necessary to add more Chinese words to the bare English phrase. However, by doing so, the abstract nature of the verb to be is distorted and the exquisite Shakespearean expression vanishes.

The Western world standing on sein...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Schlagworte | Comparative Cultural Studies • Comparative Philosophy • Cultural Studies • Culture and Personality • East and West • eastern and western culture • Eastern culture • Eastern philosophy • Jin Li • Li • Philosophy of education • Philosophy of mind • Philosophy of self • Psychology • the self in the west and east asia • to be or to become • to be or to become the self in the west and east asia • Western Culture • Western Philosophy |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6137-4 / 1509561374 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6137-7 / 9781509561377 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich