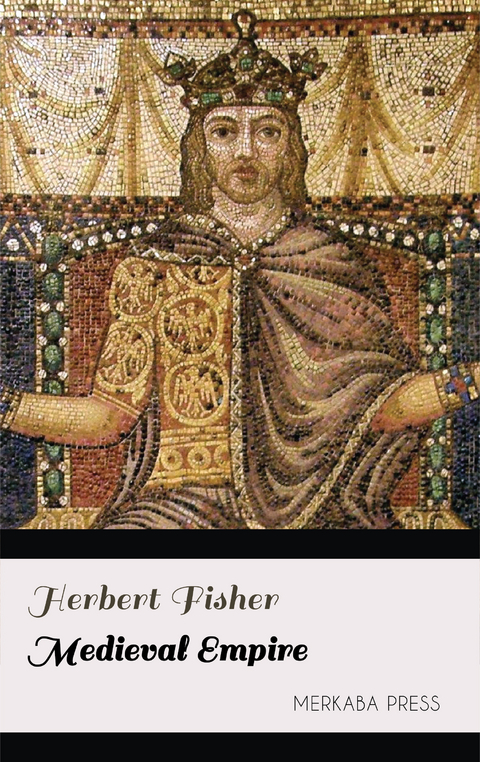

Medieval Empire (eBook)

189 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-001944-8 (ISBN)

In this essay I do not aspire to recount the narrative of the empire, or to instruct trained historians. Nor do I propose to trace the history of the imperial idea, which Mr. Bryce has exhibited in a work which it would be impertinence in me to commend. My object is to examine the working of the imperial idea during that portion of medieval history when, having assumed a definite theological shape, it operated as a powerful influence over the destinies of Germany and Italy. I wish to see how the machine of imperial government worked in these countries from the revival of the empire by Otto I. to the downfall of the Hohenstauffen dynasty. It seemed, however, necessary by way of introduction to explain why the empire survived at all, and why it was revived in 962.

CHAPTER I: THE SURVIVAL OF THE IMPERIAL IDEA

THERE is no lesson which mankind has been so slow to learn as the necessity of continuous political and social change. Each succeeding form of social and of political structure has seemed final to the men who lived under it. The greatest thinkers of antiquity, Plato and Aristotle, while recognizing the fragility of existing politics, concur in their belief that fate holds no surprises garnered in her hand. Society goes through a necessary cycle of changes. Progress is followed by degeneration, degeneration by progress, and almost all the political inventions have been already made. The mysteries of Nature may indeed, according to Plato, bring to birth a generation of men in whose hands the State will reach ideal perfection; but the ideal can be forecast by the philosopher; no long and painful prologue of evolution necessarily stands between it and the present world; and it is conceived of rather as a fixed though brittle state, than as a moving and continuous process. Even the amazing revolution of things, which is summed up in the downfall of Greek City States and the foundation of the Roman Empire, did not Affect this deeply-rooted tendency of the human mind. The destinies of man were now conceived to be bound up with the fortunes of a new polity, but the polity was to be as durable as man himself, and though bricks and stones might crumble and perish, yet the city and the Empire of Rome were the imperishable guardians of human peace and safety. Was there not an ancient auspice that Mars, Terminus, and Juventas had refused to give place to Jove himself? The boundaries of the empire would never recede. Rome, founded on an eternal pact between Virtue and Fortune, would be young and warlike to the end of the world.

To the believing Christian too, the riddle of history presented no difficulties. The origin, the intention, and the end alike of the general and of the individual life were known to him. "We," wrote Lactantius, "who are instructed in the science of truth by the Holy Scriptures know the beginning of the world and its end.” To expose the contradictions of the ancient philosopher and the crudities of the ancient creeds, to confront the perplexities of science with the certainties of faith, were the main tasks of the early Christian apologists, and nowhere was Christianity more powerful to mould and transmute current conceptions than in the domain of historical retrospect and prophecy.

It had not escaped the notice of the early Christians that the rise of Christianity synchronized with the foundation of the Roman Empire. While the empire was spreading peace and order over the civilized world, Christianity was attempting to found a kingdom in the soul of man. There was indeed a strict parallelism between the political and the religious manifestations of the divine purpose throughout history. As Abraham had divulged the will of God at the beginning of the Assyrian Empire, as the fountains of Hebrew prophecy had been outpoured during the lifetime of Romulus and his immediate successors, so Christ had come to reveal the final purpose of God at the birth of the Augustan age. Three great empires had passed away; the work of Ninus and Cyrus and Alexander was utterly dissolved, but the Roman Empire was founded to be the strong and beneficent agent through which the teaching of Christ was to be stamped upon the world. The Roman Emperor was indeed unworthy of the divine honours which his subjects lavished upon him, but he was chosen by God, he was second to God, and he deserved the loyalty and obedience of the Christian sectaries. The city of Rome was not indeed to be eternal as the Roman poets had prophesied, for mankind were not to occupy the world for ever. But the city would at any rate last till the coming of Antichrist, and the emperors were deserving of the prayers of the Christians since it was only by the Roman Empire that that awful event could be retarded. The Sybilline prophecies, which were accepted as sacred by the early fathers, and which were throughout the Middle Ages believed to exist in the Lateran, confirmed the belief in the divine purpose of the empire. It was observed too that the three languages in which, after the labours of St. Jerome, the Scriptures were written, were all languages of the Roman Empire, that the birth of Christ had synchronized with an unexampled period of universal peace; and it is one of the most remarkable facts in literary history that Virgil, the poet of the young empire, should have so caught the mystic feeling of the far-off medieval Church as to be mistaken for the prophet of the new creed. The correspondence too between ecclesiastical and civil institutions, between the Mosaic and civil law, was soon noted, and it was a natural inference that since the institutions of the Church lad been closely modelled upon those of the empire, the empire had been preordained to be the receptacle and, so to speak, the outer shell of Christian belief. The ablest ecclesiastical writer of the ninth century, Walafrid Strabo, sums up his work upon Christian institutions by a detailed comparison of the civil and ecclesiastical hierarchy as it existed in his day. "As the Emperors of the Romans," he wrote, "are reported to have governed the world, so the Pope of the Roman see, as vicar of St. Peter, is raised above the whole Church." The patricians, as being next in dignity to the emperor, correspond to the patriarchs; the archbishops who are above metropolitan rank, to the kings; the metropolitans to the dukes, the bishops to the counts, and so on down to the lowest rank in either hierarchy.

Indeed the idea of the perpetuity, unity, and sanctity of the Roman Empire was too strongly rooted in the Christian and pagan breast to perish in the rude blasts of the barbaric invasions. All the memories of the past, all the hopes for the future, were bound up in this great polity, which still appeared to be the only possible bulwark of social order. In the poem of Rutilius Namatianus, written just after Alaric's sack of Rome, we have a touching and eloquent appeal to the eternal city from a Gaul who felt the full splendour of her traditions. "Never," he writes, "have the stars in their everlasting motions beheld a fairer empire. What had the Assyrians, what had the Medes, the Parthian or the Macedonian tyrants to compare with it? It was not that thou hadst more spirit or more force, but that thou hadst more counsel and judgment. Continue to give laws which will last into Roman centuries. Alone thou needst not fear the fatal distaff."

This was the cry of a Romanized pagan; but the barbarians too felt the magic of the Roman name, and even in the midst of their ravages respected the majesty of empire. Theodoric, who practically conquered Italy for the Goths, received the patrician dignity from Zeno, and held Italy in virtue of an Imperial pragmatic. The letters of his secretary Cassiodorius show us that he preserved the imperial machinery of government, and anxiously consulted for the maintenance of Roman "civility," as well as for the preservation of the architectural splendours of Rome. Theodoric knew Byzantium too well to dream of subverting the imperial system or even of supplementing or correcting the Roman law, and when the Gothic ambassadors of Witiges were making their apology before Belisarius, the general of Justinian, they laid stress upon the fact that the Goths had never attempted to legislate, but had always accepted the imperial code. The Franks were more powerful and savage than the Goths; they were further removed from the seat of the empire, and were settled in a country in which the material evidences of Roman power were less strikingly displayed; but their conquest was prepared by a long process of Germanic infiltration, and when the final crash came it was due to the smart impact of a small warrior band capable of destroying the tottering superstructure of the political fabric, but incapable of creating institutions or materially disturbing the habits of urban life. So Clovis received titles from Byzantium, the Frankish chancery preserved Roman forms, and the Frankish administration readily adapted itself to Roman traditions. To the mind of the Byzantine official the Franks were a people who might indeed be formidable, but who held a defined and privileged position under the Roman Empire. They were allowed to coin gold, and they possessed the peculiarly Roman privilege of assisting at the games of Troy. But that they had broken away from Constantinople would have been admitted neither by themselves nor by any one else.

Some people felt that the Barbaric invasion was a tragedy unexampled in history. The poet-barrister Agathias of Constantinople was persuaded by his friends to abandon his verses and his briefs that he might chronicle the cataclysm, which was overwhelming the empire of Justinian, and his call to serious historical writing is recorded in one of the most touching and impressive passages of autobiography. But the importance of this epoch-making event was intentionally obscured in the West, and the whole influence of the Latin Church was exerted to preach a misleading view of historical continuity. In his commentary on the book of Daniel, Jerome, following St. Hippolytus, had interpreted the four empires of the king's dream to be respectively those of the Babylonians, the Medes, the Macedonians, and the Romans. It followed from this that the Roman Empire, being the last of the four, would endure till the end of the world, and although Orosius and Augustine differed in their attribution of the second and the third empires, all historians were agreed that the Roman Empire ushered in the final age of mankind. No superstition has ever been so fatal to true historical...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-001944-5 / 0000019445 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-001944-8 / 9780000019448 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 312 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich