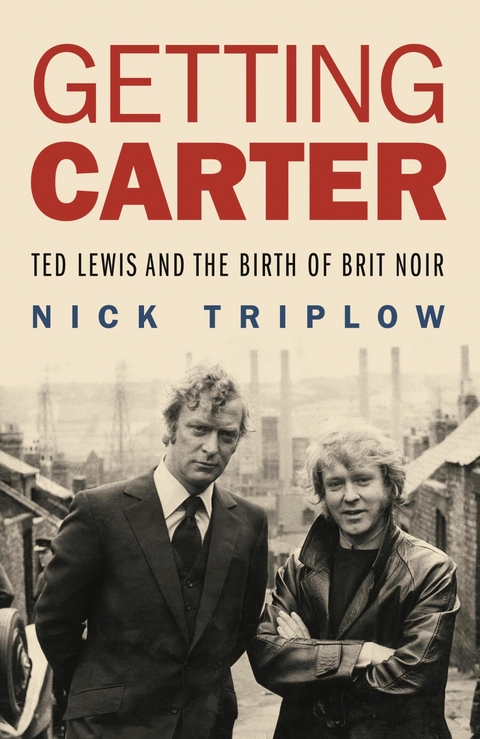

Getting Carter (eBook)

320 Seiten

No Exit Press (Verlag)

978-1-84344-883-9 (ISBN)

Nick Triplow is the writer of crime thriller Never Walk Away and south London noir, Frank's Wild Years. His acclaimed biography of crime fiction pioneer, Ted Lewis, Getting Carter: Ted Lewis and the Birth of Brit Noir, was longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger for Non-Fiction and HRF Keating Award. Nick is also the author of the social history books, Pattie Slappers, Distant Water, and The Women They Left Behind. Originally from London, he lives in Barton-upon-Humber and is co-founder of Hull Noir Crime Fiction Festival.

Nick Triplow is the author of the south London crime novel Frank's Wild Years and the social history books The Women They Left Behind, Distant Water and Pattie Slappers. His acclaimed short story, Face Value, was a winner in the 2015 Northern Crime competition. Originally from London, now living in Barton upon Humber, Nick studied English and Creative Writing at Middlesex University and, in 2007, earned a distinction at Sheffield Hallam University's MA in Creative Writing. Since completing his biography of British noir pioneer, Ted Lewis, Nick has been working on new fiction.

2

Voice of America

1951–1956

The Barton Grammar school which opened its gates to Lewis in September 1951 had been founded, like so many others, on principles borrowed from the public school system. Conservative by instinct and ethos, it sought to produce young men and women of sound learning, high academic achievement and traditional values. Established in 1931, the school had done much to elevate the town’s standing. Its teachers were among the most respected members of the community, their status as educators and moral guardians unquestioned. Entrance was by no means a formality. Earning a place at ‘the grammar’ was an achievement, an indicator of aspiration for the children of Barton’s working class and lower middle class families. For Lewis’s friends, Nick and Martin Turner, John and Alan Dickinson, Mike Shucksmith and Barbara Hewson – all former pupils – schooldays are recalled with mixed feelings. For some, Barton Grammar was the passport to opportunity their parents had worked for, fought for, and on which they’d staked their children’s futures; but it could also be intolerant of any pupil who did not, or could not, fit the mould socially and academically.

The school population, mainly from Barton and nearby villages, had been increasing year on year. By the time Lewis arrived, student numbers had risen to around 300. The proximity of the war and its after effects continued to shape the way people lived. Clothes were only available on coupons and food was still subject to rationing. Boys bragged of their shrapnel collections and told stories of the bomber crews from RAF Kirmington and the godlike American fighter pilots who had frequented local pubs – the RAF station at Goxhill had been transferred to the US 8th and 9th Air Force in 1942. Sixth former John Grimbleby would describe how he had found the impression of a German airman in the earth in a field outside Barton, the victim of a failed parachute. Luftwaffe raiders had routinely used moonlight reflecting off the Humber to navigate into Hull, turning home over the south bank. Barton people remembered the drone of bombers night after night when it had seemed as though the entire waterfront and city of Hull was ablaze. John and Alan Dickinson’s father, a wartime fireman, told stories of how his fire crew had been strafed by a German fighter at New Holland quayside – most credit went to the ‘heroic’ Salvation Army officer who continued to serve tea throughout the raid. At school, teachers returning from the services had resumed their careers, readjusting to civilian life in the classroom. Physical education and geography teacher Jack Baker still wore his khaki battledress jacket to classes, just as he had for his job interview.

The school’s headmaster, Norman Goddard, was a modern languages scholar. Hard-featured, with cold grey eyes, a Mozart specialist and strict disciplinarian, Goddard had established a fearsome reputation on his arrival in the spring of 1951. Martin Turner remembers that ‘within a week, he had tamed the school’. Boys were expected to lift their caps to senior teachers; minor uniform, timekeeping and homework indiscretions were routinely punished, with one hundred lines the standard penalty. At the conclusion of each morning’s assembly, Goddard took his place in front of the stage and read the list of names of those he wished to see. ‘If he wanted to see you at lunchtime,’ says Nick Turner, ‘it was a ticking off. If it was break time, you might be able to talk your way out of it. But if he wanted to see you straight after assembly, you were in big trouble.’ Goddard caned boys across the hand, a punishment from which girls were exempt, but which seemed only to make his verbal and psychological admonishment of them more severe. Teachers used the threat of being made to stand under the clock opposite the headmaster’s office to deter bad behaviour. It came with an ever present fear of interrogation should the door open and Goddard demand to know why you were there. Nick Turner remembers, ‘Say you’d been talking in class, he’d ask, “Why were you talking?” That was his thing, he’d say, “Why? Why? Why? Why?” again and again until you were an abject mess and you’d say, “Because I’m stupid, because I’m a fool.” He’d wear you down with the same question over and over.’ When the rumour circulated that Goddard had spent the war working for British Intelligence, interrogating captured German prisoners, no one had difficulty believing it.

In September 1951, Edward Lewis arrived in his new navy and light blue quartered cap, stiff navy blue wool blazer, polished shoes, striped tie and grey flannel trousers. Still finding his feet a few days into the new term, he was leaning against a wall near the boys’ entrance to the playing field, hands in pockets, hair uncombed, tie loose around his shirt collar. Taking exception to this apparently insolent attitude from one of his boys, particularly a first former, Goddard walked purposely towards him. Lewis, 1M wasn’t it? After a sharp ticking off, Goddard slapped him hard across the face. The shock of the assault caused Lewis to wet himself. Goddard continued with his lunchtime inspection, leaving the new boy to clean himself up.

For the pupils, many of whom had recently arrived from village primary schools, none of whom had witnessed anything quite like it, this was a salutary lesson. They might have been used to corporal punishment – in common with most lads, Lewis had been ‘walloped’ by his father for misdemeanours in the past and there was the memory of Miss Crawford – but this was different. Goddard had decided to make an example of him. News spread through the school that ‘Ed Lewis had pissed himself’. Inevitably, for the next few days he ran the gauntlet of snide comments. For the most part, his friends recall that these did not last and he was treated with sympathy; others, you suspect, were less kind-hearted. A new boy in a new school, he was humiliated and now vulnerable, knowing the incident was in reserve for the opponent in any argument. While Harry and Bertha may have disapproved, they weren’t about to challenge their son’s new headmaster and the episode was to remain with Lewis for the rest of his life. In his 1975 novel, The Rabbit, he included a graphic retelling of the story of the headmaster’s slap, the sickening sensation of wetting himself in public and locking himself in the toilets until everyone had gone home.

Lewis’s introduction to the school could hardly have been worse. The quiet distaste for authority he’d begun to nurture at Barton County grew deeper and he withdrew further. As others fell into line, conforming to the everyday rigours of school life, the injustices – real and perceived – hurt him deeply. Unfortunately, his place in the modern language form 1M brought him into regular contact with Goddard who would take the class for German lessons. Here Goddard reserved special treatment for boys not paying attention, pulling up the desk lid at the same time as sharply pushing the boy’s head down. Inevitably, there were bloody noses. For entertainment one Friday afternoon, he sat them to attention on PE benches in the school hall and played an LP of Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. In the verbal examination that followed, Nick Turner remembers, he asked, ‘Had we heard this part or that? And if not, why weren’t we listening?’ For Lewis, always nervous in Goddard’s presence, lessons like these were unbearable.

Reading Enid Brice’s book, A Country Grammar School Remembered, which tells the story of the school, there are former pupils who consider Goddard embodied a necessarily ‘strict but fair’ brand of school discipline. It was hardly unheard of for 1950s schoolteachers to be authoritarian and corporal punishment was commonplace, but this seems different. Years later, on being told he had terrified one former pupil, Goddard said, ‘Ah, but it worked, didn’t it?’ Mike Shucksmith thinks otherwise. ‘There were tough teachers, and you respected them. I got it a couple of times for being a silly bugger, but Goddard was a shit. I hated him.’ Interviewed by the Manchester Evening News in 1970, Lewis would recall an occasion he’d been seen eating fish and chips in the street and was publicly rebuked by Goddard for ‘eating comestibles out of a paper bag’. It was not the kind of thing a Barton Grammar School boy ought to do. Lewis warmed to his theme, ‘If you weren’t a machine storing up maths, French, and anything moving away from the arts, they’d frown on you. I’ve written three novels and the first, about school, was rejected. The publisher I took it to at the time considered it libellous.’

Life outside the school gates offered plenty of distractions. In July 1952, the Lewises moved from West Acridge to a larger property at nearby 46 Westfield Road, a few doors down from the Shucksmiths. The new house, bought for £1,500, had previously belonged to a local doctor, Charles Hawthorn. It had a sizeable basement and attic and, in the front room, stood a newly bought upright piano on which Lewis began having lessons with a local teacher, Harold Johnson. Outside there was a small piece of adjoining land with an orchard and a few chickens. In the garden, which had a small, deep dip-pond filled with foul-smelling water, Lewis and his friends were soon making the most of the space, experimenting with homemade artillery, firing rockets along a length of drainpipe through an old dustbin lid. Health and safety was of the ‘duck when you see one coming’ variety. Past the pond and through...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.10.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Biography • british crime • brit noir • city of culture • Get Carter • Hull • Hull Noir • Jack's Return Home • Michael Caine • Mike Hodges • Rags to Riches • Ted Lewis |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84344-883-1 / 1843448831 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84344-883-9 / 9781843448839 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich